Generally, businesses exist to make a profit. The moment any individual or group of individuals come together to provide a product or service—essentially meeting a need, the sole aim of that venture is to ensure that money spent (capital) is recouped and increased (profit).

Today, our focus will be on profit margins—net income. That’s basic accounting speak for when we take expenses, including taxes, out of revenue. Companies can make a gross profit but still be regarded as unprofitable ventures because their profit margins are extremely low or negative.

Key takeaways

-

Airlines are low-profit margin businesses due to the high cost of capital and operating expenses that they cannot pass down to passengers as demand is price elastic

-

In Nigeria, airlines were struggling before the Russian-Ukraine war, and now their costs have spiked to unsustainable levels, with aviation fuel (Jet A1) as the primary culprit

- With other factors, including forex

In that sense, it has been established that running an airline is not a highly profitable business due to the high cost of capital and operating expenses involved compared to the revenue generated. Because passengers (the primary source of income for airlines) are very price-sensitive, airlines find it difficult to immediately pass the burden of higher costs to the passengers through increased ticket prices—essentially dampening their pricing power. This, in addition to the existence of many government-subsidized airlines, makes it harder for other private-owned airlines to change prices at will—it would erode competition and force consumers to move to cheaper airlines. The demand for airline services has become price elastic, i.e., for every price increase, there will be a shift in the demand curve as consumers will most likely move to other substitutes. And airlines cannot afford to take such a huge risk.

So, will Nigerian airlines be profitable soon?

Well, first we need to understand the economics of the airline business, provide some context about the current events unfolding in the Nigerian aviation industry and then, with the evidence provided, we can attempt to answer the question.

The business model for airlines

Before we get to the model and number breakdown, there are a few important things to note.

First, there is no room for errors or mistakes in the airline business. Why? People’s lives depend on the safety of the aircraft and the efficiency of the airline. So, every airline looks to hire the best and most qualified personnel and ensure that maintenance and safety checks are done to the last detail—all increasing costs. The airline would rather incur charges than allow an air crash.

Second, according to research done by the Wall Street Journal, the profit margin for airlines is only about 1% of the actual revenue they generate daily. So, for every $170,000 made, the airline makes a meagre profit of $170.

Third, this is not to say that no airline makes a profit. For example, in 2018, Air France (KLM), which carried more than 100 million passengers, recorded a profit of $463 million, a 150% increase compared to the previous year. Another example is Delta Airlines, which operates over 5,400 flights yearly, serving 325 destinations in 52 countries. The airline made a pre-tax profit of $5.2 billion in 2018.

But this was in 2018, two years before the covid-19 pandemic (2020) and five years before the Russian-Ukraine crisis.

Additionally, even with these pre-tax profits, the net profit margins are typically small (as mentioned earlier). Besides, when and if airlines make profits, it is often due to operating in a policy friendly environment. And this happens through bailouts and growth-enhancing policies from the government of their various countries. For example, in Biden’s infrastructure bill ($1 trillion) passed by the US Senate in 2021, $25 billion was set aside to alleviate the US airline industry (airports included) from the impact of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

Fourth, in 2020, the global aviation industry received massive blows from tepid passenger demand as lockdown measures were in place, which crippled revenue and profits. A good example would be South African Airways. Like many other airlines, the company filed for bankruptcy before the pandemic, and during covid, the airline almost went extinct.

Fast forward to today, the Russian-Ukraine crisis has triggered a sharp increase in the global price of crude oil and, in turn, increased the cost of aviation fuel, which has worsened airlines' operating expenses all over the world. Aviation fuel is the most significant thing eating away at a profit for airlines.

When profit margins are low, expectations of bankruptcy and sustained losses increase. But the airline industry is accustomed to bankruptcies and losses. American Airlines, United Airlines, and Delta had once filed for bankruptcy before mergers saved them.

The famous American business magnate and investor Warren Buffet once said that the worst sort of business is one that proliferates, requires significant capital to engender growth, and then earns little or no money. In summary, airlines tick these parameters highlighted by Buffet.

So far, we have established that running an airline requires enormous capital and running costs like aviation fuel. We now also understand that airlines cannot successfully pass the burden of higher costs to consumers (passengers), and this continues to shrink their profit margin.

But how do airlines make money?

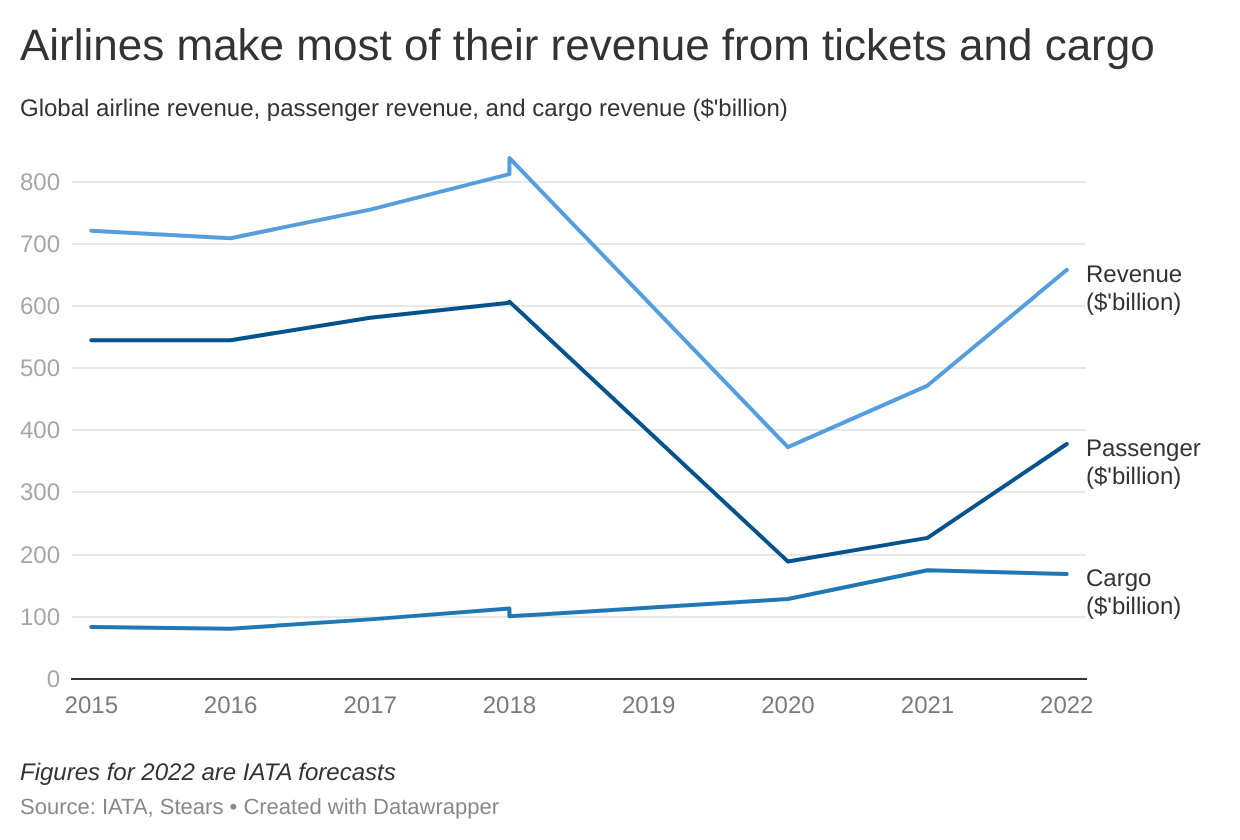

Airlines generate income from two primary sources, passengers and cargo, and in both categories, volume is critical, meaning that the more passenger traffic, the more revenue and profit. The same applies to cargo services. However, the demand for airline services can be disrupted by unforeseen circumstances like weather or, as it was in 2020. According to the IATA, global passenger traffic fell by 60% in 2020 to 1.8 billion and 50% to 2.28 billion in 2021 from 4.54 billion in 2019. And this led to the global aviation industry making a net industry loss margin of 37% (-$137.7 billion) and 11% ($-51.8 billion) in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

Ticket sales to a massive number of passengers are the revenue generation point. And airlines try to make as much money by charging different prices to different classes of individuals. We have spoken about the price discrimination strategy of airlines extensively before. For example, if you booked a flight two weeks before your proposed travel date, you’d probably get a cheaper ticket than if you booked the day before your travel date. Also, the travel destination could be the additional reason the cost of a passenger’s ticket would be more or less. Price discrimination in aviation is based on time, preference (economy, business, first-class), and location.

Airlines also try to milk extra income from charges on baggage, charter services and exquisite dining service.

How do airlines spend money?

Business Insider explains that in the United States, at least 30% of airline revenue is spent on aviation fuel, 20% on salaries, 16% on ownership costs, 14% on government fees and taxes, and 11% on maintenance; other costs take about 9%. So, airlines have to deduct these recurring costs for every ticket sold.

Sadly, whether or not people fly, some of these costs never stop. For instance, if an airline purchases an aircraft and cannot travel at full capacity due to low passenger traffic, the costs to the airline do not evaporate. The airline will still fuel the plane, pay crew member salaries, offer catering services, and ensure maintenance checks and taxes are covered. Meanwhile, the revenue gotten based on the tickets sold is sub-par. If the aircraft is leased, repayments will have to be made. Essentially, you have airlines running both high fixed and variable costs. The variable costs for an airline will increase as passengers increase (like catering) while fixed costs like lease payments, salaries etc. are constant. Once a flight is going from London to Lagos, the cost of the airline embarking on that flight, whether or not the plane is filled with passengers, does not reduce. And this cost structure is why airlines always seek to maximise passenger revenue.

To further contextualise the cost for airlines and how deeply rooted this goes, here’s the summary of an insightful illustration I found on Quora.

The assumptions are 1. A small airline, with one aircraft that can seat 156 people, 2. An average passenger load factor of 78% or 124.8 seats sold per flight and 3. An average industry profit of $8.27 per passenger.

If the airline provides a service of 16 flights per day. It would amount to:

$8.27 x 124.8seats x 16 = $16,513.54 profit per day

$16,513.54 x 365 days = $6,027,442.10 profit per year

If the airline had to cancel about 80 of their scheduled flights in a year, probably due to bad weather or a pandemic or war, $8.27 x 124.8 x 0.8 = $82,567.60 would be deducted from the annual profit of the $6 million. Remember, certain costs like fuelling, salaries, taxes, fees, and maintenance are already running.

In a case where for 50 of these cancellations, the accommodation is not until the next day, and the airline has to pay an additional hotel cost for about 90 passengers for $95 per night, that would be 50 x 90 x $95 = $427,500.

If each passenger then gets a meal voucher worth $20 per person. That's another 124.8 x 80 x $20 = $199,680 taken out from the estimated annual profit of $6 million.

While $6,027,442.10 could have been made, $82,567.60 + $199,680 + $427,500 = $709,747.60 will be lost, bringing the profit a little over $5 million.

If the situation gets terrible, and the airline decides to put the passengers on another carrier, for an additional ticket cost of $600 each, then: 124.8 x 80 x $600 = $5,990,400, which means goodbye to the profits. This hypothetical illustration shows just a glimpse of what airlines go through financially.

In Nigeria, the dynamics are pretty much the same.

So, how are Nigerian airlines faring?

Before the Russian-Ukraine tensions, Nigerian airlines were already struggling with increased costs compared to revenue generated. Think of Medview. And these issues were also happening despite the increase in insecurity that should have moved demand from road transport to air transport. Before getting into the details of how airlines are currently doing, let’s take a brief look at the structure of the Nigerian aviation industry. The goal is to see how many bodies airlines have to interface with and pay charges, fees, or levies:

-

The Federal Ministry of Aviation is the body that oversees all aviation-related matters in Nigeria.

-

Nigerian Civil Aviation Authority (NCAA) serves as the “police” of the industry, providing oversight, safety, standards and other regulatory functions.

-

Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NIMET) provide data and advice on climate and weather conditions.

-

The Accident Investigation Bureau (AIB) is responsible for investigating air-related accidents.

-

Nigerian Airspace Management Authority (NAMA) is responsible for air travel control, communication, surveillance, and navigational facilities.

-

Nigerian Aviation Handling Company (NAHCO) provide ground handling services to airlines.

-

Airline Operators of Nigeria (AON) is the body of nine private airlines in Nigeria—Ibom air, Air peace, Max Air, Azman Air, Aero Contractors, Dana airways, Overland Airways, Arik Air and United Airlines Nigeria. AON now functions like an oligopoly that determines the price of flight tickets across the country.

Now that we know the critical bodies in Nigeria’s aviation industry. Let's take a look at what is currently happening.

While speaking to Mr Anukewe Ferdinand (a licenced NCAA engineer), Mr Ina Godwin (Head of operations with Grandeur World Integrated ltd) and Mr Roland Iyayi (CEO of Top Brass aviation), the recurring theme was “government interference”.

The issue here is fragmented and complex. The aviation industry in Nigeria is not adequately supported by government policies and regulations to help domestic carriers thrive, grow and make reasonable profits. Take a situation where the Nigerian aviation authorities allow international carriers access to local airports. So, instead of dropping passengers that probably came from Ethiopia at airports in Abuja and Lagos, the airline can drop passengers at Port Harcourt and Enugu airports. This decision could hurt passenger revenue for local airlines because local airlines should have had access to these passengers, providing them with a connecting flight from Lagos or Abuja to Port Harcourt and not the international carrier.

Another government-related issue is the regulatory bottlenecks. Imagine a brand new aircraft purchased is not allowed to begin operations for almost a year due to paperwork that could have been sorted way before the plane landed in the country. The airline will still pay costs for maintenance, parking of the craft, and other fees, without earning a dime with the aircraft.

Still, on governance, remember I mentioned that the government of various countries support airlines by providing funds to cushion rising costs. In Nigeria, the federal government released ₦4 billion as a bailout fund for airlines under its ₦26 billion approved COVID-19 intervention fund for the aviation industry. But when you put this fund side by side with the 268% increase in aviation fuel (that the government should have been producing and refining by now), the ₦26 billion bailout fund is practically gone.

As Mr Roland Iyayi puts it, the business environment for airlines is very hostile.

The second most significant problem for Nigerian airlines is aviation fuel (Jet A1), accounting for about 40% of airline costs. This expense is tied to the exchange rate fluctuations, making it even worse. Over time, the price of aviation of fuel has climbed from ₦190 per litre to ₦700 per litre. Due to the rise in the price of aviation fuel, the cost of operations for airlines is currently up by 95%. And this cost, according to AON, should push up the ticket price per seat for a passenger to ₦120,000 from the already existing price floor of ₦50,000. But as we have agreed earlier, this is unlikely to happen because consumers (passengers) are very price-sensitive, and airlines would rather be in operations than risk low passenger revenue. So airlines are absorbing the 268% increase in aviation fuel costs to keep ticket prices at ₦50,000-₦55,000.

Maintenance costs are also a big part of the issue for Nigerian airlines. What makes this problematic is the issue of forex. First, aircrafts undergo periodic checks—A, B, C, and D. C and D checks are the most important for any aircraft to be cleared to fly. These checks are costly, especially for airlines that send the aircraft abroad for maintenance and then pay in dollars or bring down foreign experts to undergo these safety checks here in the country. The crash in the naira to ₦600 per dollar at the parallel market and ₦419 per dollar at the official window (IEFX) has made it difficult for airlines. Besides, forex is scarce in the official market as election spending ramps up.

The final most significant cost to dimension is “lease”. Most Nigerian airlines do not have aircrafts of their own because of the high-cost implications. For instance, the price of a brand new Boeing 737 that Nigerian airlines use ranges from $70 million to $110 million (₦29 billion to ₦46 billion using the IEFX rate of ₦419 per dollar). So, leasing is the best option. Unfortunately, these lease payments do not end until the airline completes full payment and most times, the amount is in foreign currency (dollars). Again, the issue of forex rears its ugly head.

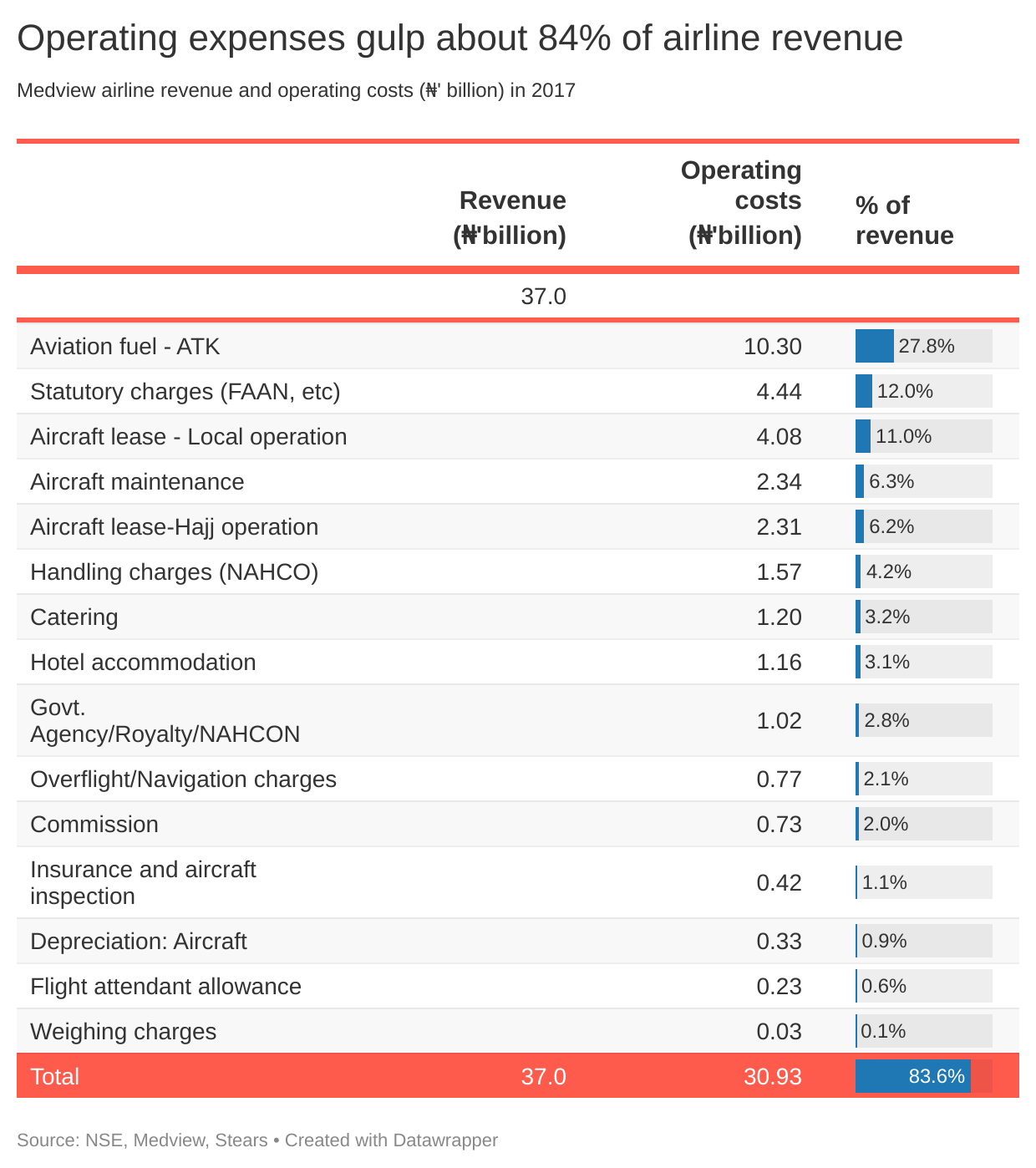

The costs mentioned above are in addition to other recurring costs like staff and crew members, who must undergo training from time to time. The airlines also provide catering services on flights (which some are beginning to cut now) and the fees they pay to regulatory bodies. Since there are no recent airlines listed on the Nigerian stock exchange, let me bring back Medview's operating costs as of 2017, so you can visualise the costs better.

Airlines bearing these outrageous costs raise eyebrows about their profitability.

What next?

After reviewing the current trends in the Nigerian Aviation industry and the business model for airlines, it is unlikely that Nigerian airlines will be profitable soon. Nigerian airlines have thrived in the past; think about Okada air, Chanchangi and Bellview. They are not here today, and they were not operating in the uncertain business environment that exists today.

That’s why my outlook for the aviation industry is very bearish.

For starters, the costs we looked at are not going anywhere soon. For example, the cost of aviation fuel could rise again as global oil prices spike to $120 per barrel. Also, forex illiquidity and the value of the naira crashing are likely to continue as the four significant sources of forex to the government—oil exports, non-oil exports, diaspora remittances, and foreign investment inflows (direct and portfolio) are all declining. So, the CBN has less in its foreign reserves to draw down and defend the naira. The level of external reserves has fallen to a seven-month low of $38 billion. In terms of government policies, until aviation experts are in positions of authority in the national assembly (NASS) and other regulatory agencies, these issues will persist, further stifling growth for airlines.

In response to all these rising costs, I believe the AON might attempt to increase flight ticket costs again. There could also be some layoffs, all in a bid to cut costs.

In terms of solutions, the government could provide periodic bailouts, when necessary, to the airlines. However, the caveat here is that revenue is a big problem for the Nigerian economy. There are no chances the government will subsidise aviation fuel (jet A1) to make the costs cheaper for airlines. Another solution could be mergers. Airlines that are already overburdened and likely have no chances of survival could merge. As I mentioned earlier, top American airlines like Delta did this some years ago. Codesharing is another option. Two airlines can share passengers through codes. So, instead of airline A absorbing the cost of low passenger traffic and delaying flights to make up for the shortfall in a bid to cut costs, airline B could come in to save the day at an agreed price to be paid by airline A. So, there is one aircraft in use, fuel costs have reduced, and passengers are happy.

If all these issues plaguing Nigerian airlines are not addressed, we risk more airlines folding up as we have seen in the past.