Loans are and have always been crucial for economic survival. Many businesses need them at various points in their lifecycle to power up economic activities from production to employment or meet other specific goals.

The most recent EFInA report shows that 51% of Nigerian adults want to invest in a business. Yet, few Nigerians take bank loans to meet their goals. The same EFInA report recorded that only 5% of Nigerians used loans from formal institutions to meet their goals. A huge number (26%) did nothing, while about 40% used non-financial mechanisms such as working more.

-

One of the core mandates of commercial banks is to lend out money. Banks make significant income from lending and help businesses and firms expand. However, lending from Nigerian banks has dropped over time.

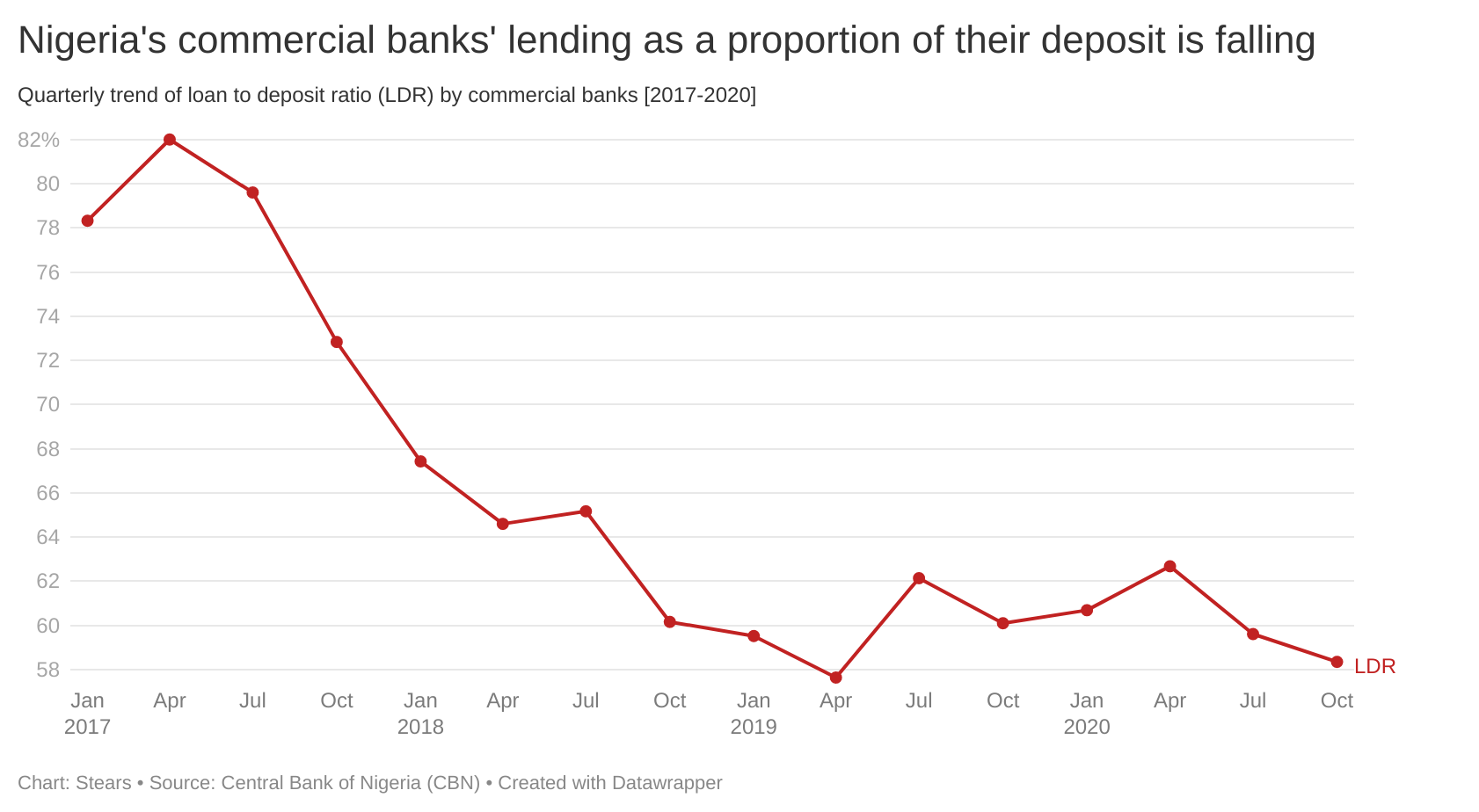

- Between 2017 and 2020 the proportion of bank loans compared to deposits has dropped by 26%. In addition, with a

Interest income from loans is the lifeblood of financial institutions, particularly banks. For example, income from loans and advances to customers made up 38% of Zenith Bank’s group ₦766 billion gross income in 2021.

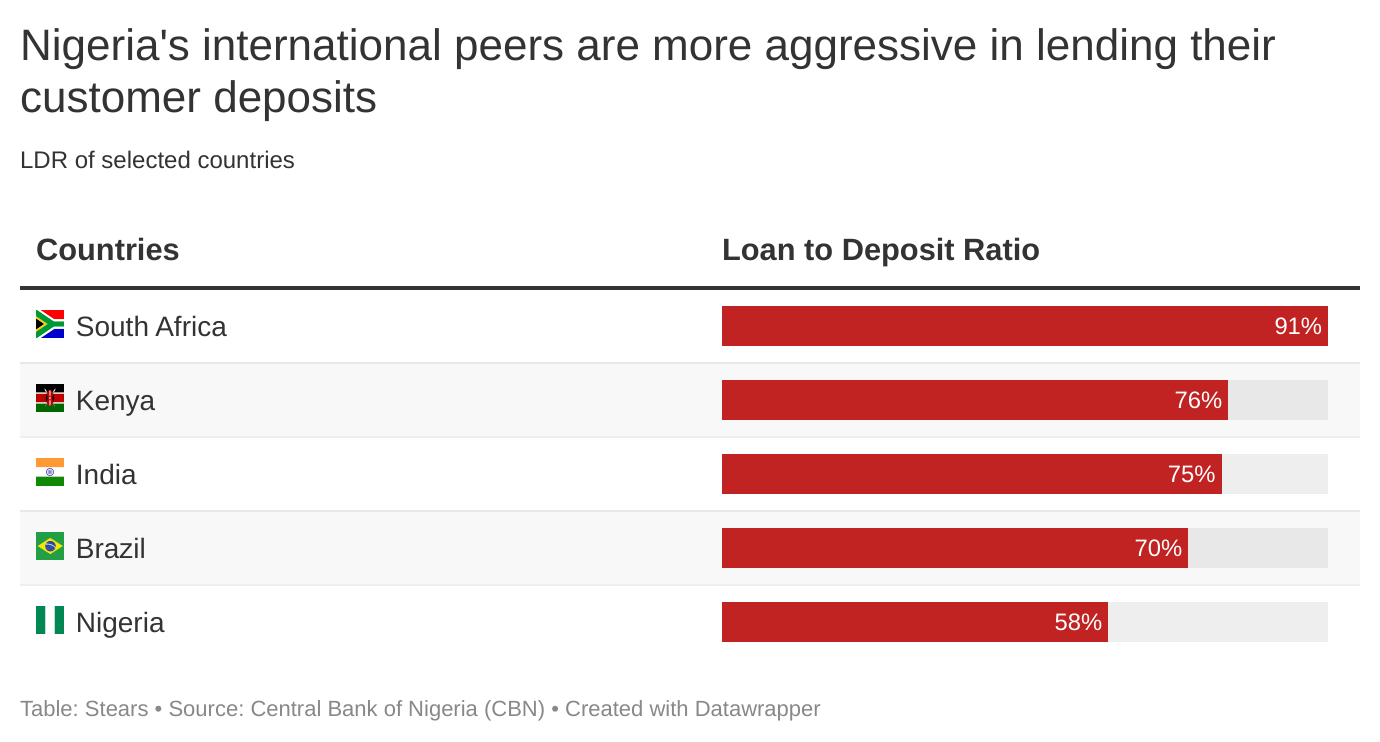

Interestingly, Nigerian banks do not give out loans as aggressively as their international peers. One way to spot this is by closely looking at the proportion of loans banks give out and comparing it to the volume of their deposits. This is known as the “Loan-to-Deposit Ratio (LDR)”.

As of Q4’2020 LDR for Nigerian commercial banks was 58%. This is low compared to other countries that give out as much as 70% and 90% of their deposits.

The CBN did not like this because, obviously, loans are pretty important and have significant economic benefits. However, not only was the commercial banks’ LDR low, but it had also fallen significantly over time.

This prompted the CBN’s 2019 LDR directive. First, the apex bank increased the minimum LDR to 60% in July 2019 and shortly after, in September of the same year, pegged LDR at a minimum of 65%.

In this story, we will look at why the LDR is low and why lending higher portions of deposits for Nigerian banks is elusive compared to their peers in other climes.

The lending picture

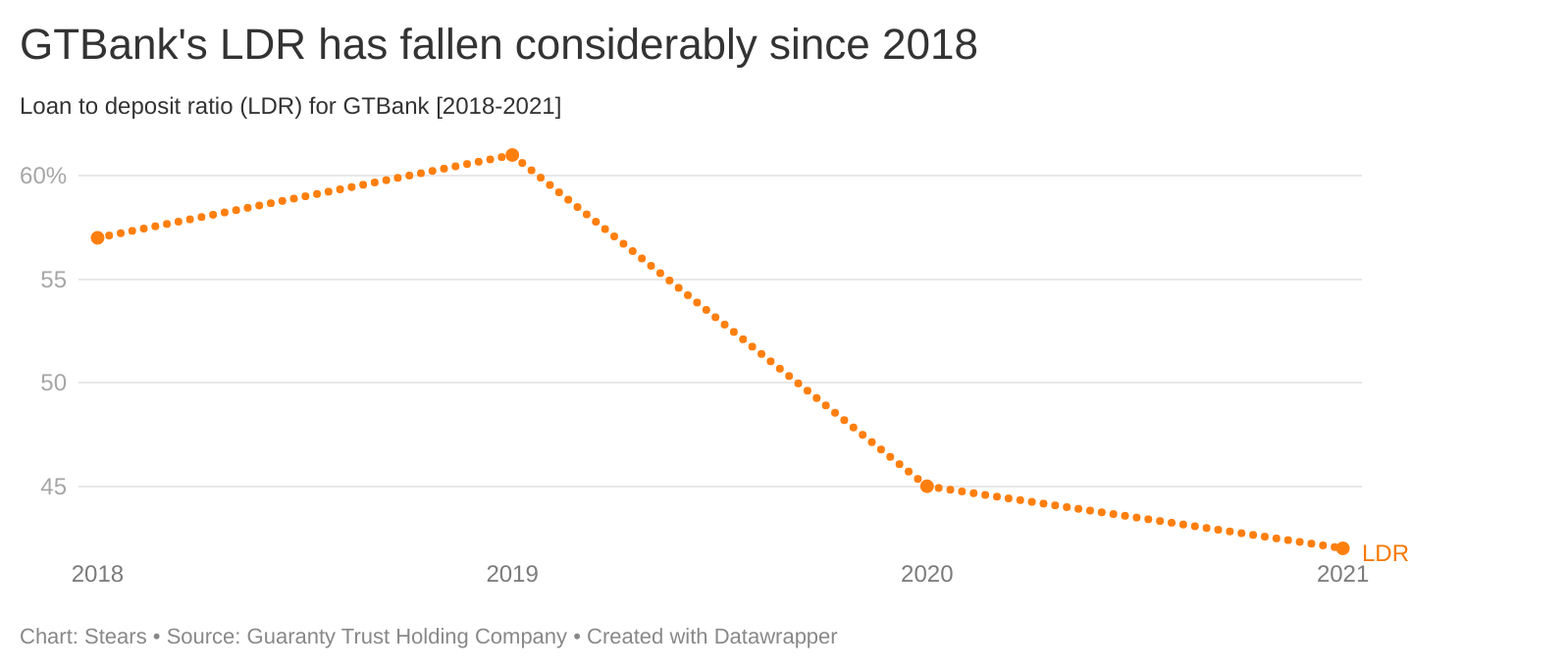

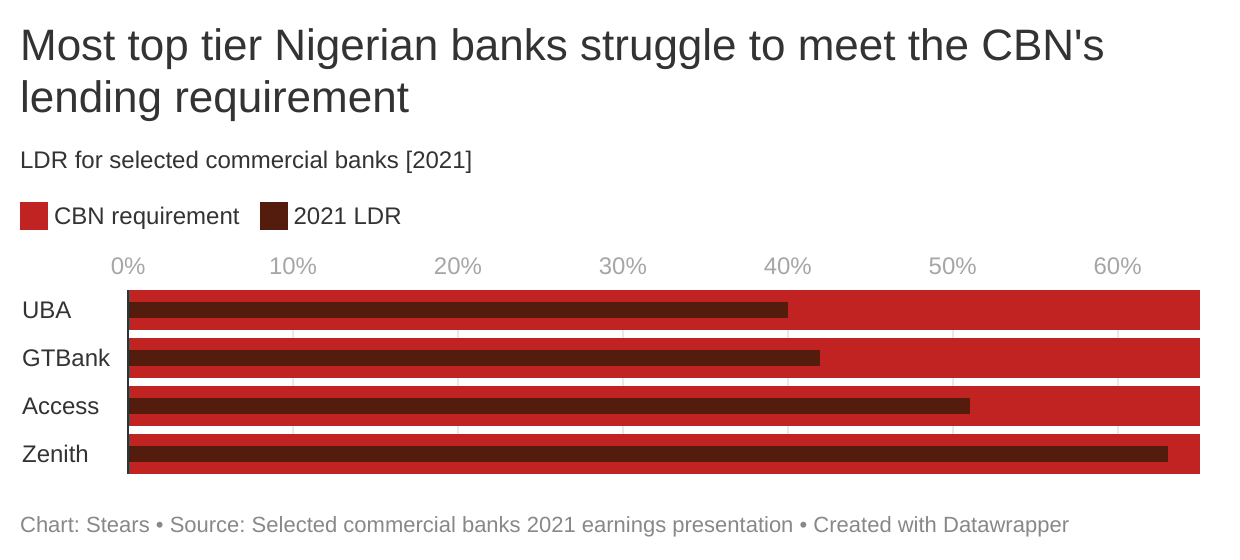

A bank that lends all of its deposits will have an LDR of 100%. However, recent financial reports of Nigeria’s biggest commercial banks show that some banks are not lending up to half of their total deposits. For instance, last year, GTBank, the commercial banking arm of GTCO, gave out only 42% of its deposits as loans, down from 45% and 61% of its deposits given out as loans in 2020 and 2019 respectively. In its most recent investor presentation, the bank outlined that it would give out only half of its deposits as loans in 2022.

GTBank’s data mirrors the sentiment in the banking industry. LDRs for other top banks such as UBA and Access Bank are also significantly lower than the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) directive of lending at least 65% of deposits.

For instance, UBA’s LDR fell from 43% to 40% between 2020 and last year. For Access bank, the drop was from 54% in 2020 to 51% in 2021.

However, LDR is a function of both loans (numerator) and deposits (denominator). So one might justify the declining LDRs by explaining that deposits are rising faster than loans, meaning that LDR is bound to fall if the change in loans is significantly lesser than the change in deposits. Imagine that loans grew by only 5% for Bank A but this bank’s deposits increased by 10% in the same period, automatically, its LDR will fall.

But essentially, the point of the CBN’s LDR floor is for banks to lend an appreciable portion of these deposits to help stimulate the economy. So, the obvious issue here is that institutions with the ability to lend are not lending as much as they can. Another issue is the disregard for the CBN lending requirement. Yet, when we compare this situation to other markets, the CBN’s requirement or demand from banks to lend seems reasonable. For instance, in South Africa, which is home to Africa's largest banks, LDR for the likes of Absa, Nedbank, and Standard Bank was 84%, 83%, and 80% respectively, last year. Although these banks’ LDRs were recorded to have been dropping from previous years, on an aggregate level they are still higher than what Nigerian banks—even those with relatively higher LDR (e.g. Zenith Bank)—are happy to lend.

Why is this so and why can’t the CBN enforce its LDR requirement?

The root of low lending

The answer boils down to several things, one of which is the structural issues that most Nigerians are familiar with. Think about the harsh economic headwinds, lack of credible borrowers, insecurity, etc., which make lending to many businesses a high-risk venture.

So even with the CBN mandating commercial banks to lend 65% of their cash deposits, and enforcing it by taking at least 50% of the shortfall when they don’t, banks still do not lend enough. For context, if a bank ends a financial year with a 55% LDR, that means it has 10% to meet up with the LDR requirement. Now, if that 10% is equivalent to ₦10 billion, the CBN would take at least ₦5 billion (50%) out of that amount, and the bank will not be able to use it to make money. However, the bank will then have the liberty to spend the other ₦5 billion in a way that they prefer. Obviously, this will not be on loans but on other investments which we will get to look at more closely in a bit.

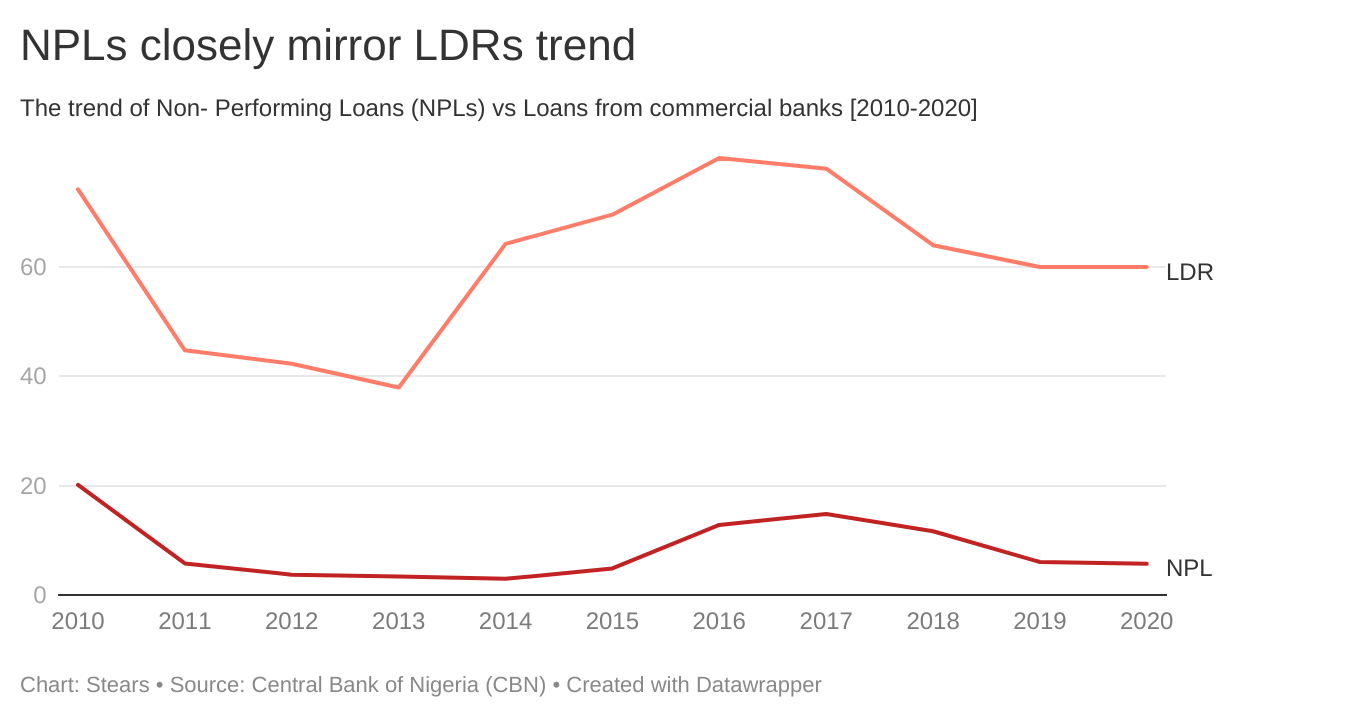

Several financial market analysts who spoke with Stears on this issue explained that banks see the CBN holding on to their funds as a safer bet than lending out money that could become bad loans. These banks' recent experience makes them reticent to lend aggressively, as they are still traumatised from a period of high non-performing loans (NPL) in the country. For instance, when LDRs were over 70% in 2010, the ratio of non-performing loans to total industry loans rose as high as 20% in the same year, much higher than the CBN threshold of 5%.

Ayodeji Ebo, the head of retail investment at Chapel Hill Denham, explained that top commercial banks in the country forgo 40% or more of their deposits to the CBN, even though they earn ₦0 on these funds. The thinking here is that a bird in hand is worth more than a thousand in the bush.

Their reasoning is not hard to imagine considering the series of events that the world and Nigeria have been going through. Essentially, banks don’t know who is risky or safe so they don’t lend to anyone. Worse, Nigeria is a peculiar country where price controls worsen and complicate economic outcomes.

So, it’s not so difficult to picture how it has become increasingly hard for well-meaning businesses to meet their projected ability to repay loans. The high cost of production, and low purchasing power, driven by high inflation and stagnant salaries have put many businesses in a state of slow, low, and negative growth. In addition, there is the issue of not being able to properly identify retail debtors or recover collateral when debtors default. Nigeria’s address verification system is porous. So even with the introduction of the Bank Verification Number (BVN) and the CBN’s approval to debit defaulting debtors across accounts in the industry where the debtor has funds, recouping loans might be hard if such debtor has no funds anywhere else. Consider that credit bureau coverage in Nigeria remains lower than in African peers.

So banks also try to mitigate the risk of lending to potentially risky businesses. For instance, the oil & gas sector loans—the former darling of financial institutions—now make up a much smaller share of total loans than before the LDR directive. It dropped 4 percentage basis points from 23% of total loans in 2019 to about 19% last year. An explanation for the decline is how the oil sector tends to be highly susceptible to economic shocks. In contrast, lending to SMEs, retail, mortgage, and other consumers has risen from about 7% of total loans in 2019 to 9% in 2021. Still, the proportion of loans to these relatively less-risky sectors is still low, suggesting there is a chunk of deposited funds banks can play around with.

So what are banks doing with the remaining bulk of deposits?

Not lending but investing

Banks are investing these deposits and earning income on them. For instance, banks use their funds to invest in “safer” corporates and earn returns. One of the key contributors to Access Bank’s interest income last year was the 32% growth in income from investment securities. Whereas the bank’s income from loans and advances grew by a lower margin of 20%. Opportunities for these kinds of investments have been occurring recently as businesses go to the capital market to raise cheap finance (long term & short term). For example, corporates like MTN, Flour Mills, Nigerian Breweries, and Dangote Cement have raised funds via commercial papers (short term) at low and mid-single digits.

Banks are also known to play in the currency and short-term fixed-income securities market, i.e. buying and selling foreign currency and investing in government short-term treasury bills and the CBN’s open market operations. Although, this is fast changing, especially for the currency market, as you might recall a recent directive from the CBN stating that it will no longer sell forex to banks by the end of the year. Still, treasury bills offer an alternative to banks looking to invest deposits and get good returns. Another look at Access Bank’s books showed a 27% increase in net trading income of ₦145 billion in 2021 from ₦114 billion in 2020. According to the bank, income from trading grew on the back of efficient treasury activities.

The key point here is that banks are actively pursuing other means of growing their income besides lending. And as long as lending proves to be challenging, banks will do what is necessary to preserve their capital, i.e. the deposits we have given to them.

In an ideal world, fixing the economic and social headwinds from lack of power, transportation, safe and secure business operating environment, that make lending unattractive, can make banks issue more credit to businesses on favourable terms. Furthermore, addressing the fundamental problem of credit data infrastructure would unlock lending to the real sector. In turn, businesses will feel more confident requesting loans and engaging in economically stimulating activities.

But fixing these issues is not the job of banks alone, and when these issues will be fixed remains elusive. So while banks’ core mandate might be lending, it should no longer come as a surprise that banks will only lend to a selected few. Most times, this will be to people or businesses that they believe can pay back loans, while they find other lucrative means of multiplying deposited funds, even if it hinders economic growth.