A lot has changed since the internet was invented back in 1960. In its earliest days, the internet was used by the US Defense Department to ensure armed forces could communicate during the Cold War. I’m no computer expert, but research shows that the computers used to connect the nascent network were big enough to fill up an entire room and consisted of a series of flashing buttons, and toggle switches.

Key takeaways:

-

Internet connectivity has come a long way globally. But sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Nigeria is struggling with poor internet infrastructure leading to high internet poverty.

-

The good news, however, is that Google plans to solve this problem through Equiano—its subsea internet cable that will run from Portugal to South Africa along the Atlantic Coast of Africa.

-

Subsea cables or underwater networks of cables carry telecommunication signals that connect countries to international internet exchanges and high internet speed.

- While

Under the sea

Today, 98% of international internet traffic is ferried around the world by subsea cables. Our ability to Facetime, book a holiday online or find an address on Google Maps is made possible by an underwater network of cables (also called subsea cables) that crisscross the ocean. These cables carry telecommunication signals across the continents of the world and connect countries to international internet exchanges, which helps users access the internet at high speeds.

As the ways we work, travel and connect evolve to become increasingly digital, reliable connectivity is more important than ever before. I previously covered the World Data Lab’s Internet Poverty index to give some insight into the need for further investment in internet infrastructure. The lowdown was that with 58.3% of its population being internet poor, sub-Saharan Africa is the most underserved region in terms of internet infrastructure. In Nigeria, nearly half of the country’s population lives in internet poverty. Existing infrastructure is unequally distributed, which leaves a vast proportion of the continent’s population without internet access that is affordable, reliable, and of good quality.

That’s what makes Equiano, Google’s subsea internet cable that will run from Portugal to South Africa along the Atlantic Coast of Africa so exciting. The investment was first announced in 2019, and is Google’s 14th investment in internet subsea cables but the first one to be dedicated to internet access in Africa. The initial configuration of the cable system will include landings in Lagos and Capetown, with branching units in place for further phases of the project.

Ultimately, internet costs and quality are a function of digital infrastructure above all else. The more advanced the digital infrastructure (cables, 5G), the higher the quality and eventually, the lower the cost.

In addition, network infrastructure investments like Equiano bring significant economic activity to the regions where they land. According to this report, Google’s historical and future network infrastructure investments in Japan are forecasted to enable an additional $303 billion in GDP between 2022 and 2026. Disclaimer though, I should add that I’m wary of forecasts or projections as they tend to be based on fallible models. Regardless, an extensive body of research confirms the impact of increased investment in broadband on economic growth. According to the World Bank, a 10% increase in developing countries is associated with a 1.4% increase in gross domestic product (GDP). Connectivity can drive development by helping to bridge information gaps, connecting remote areas to key markets and services, and boosts productivity.

It’s all great, but it’s important to think about the consequences of who is doing all the building of this very crucial infrastructure.

Why we care about who builds

Talking about who builds infrastructure and why it matters is an argument I love to revisit because whoever builds a thing determines the shape of it.

For example, if the development of a road is fully funded by the government, the typical way it gets paid for is through taxes on citizens. However, a similar good provided by the private sector might look more like a toll on the road, which can lead to users who cannot pay being excluded. In the case of taxes, even those who don’t pay taxes can still benefit from using the road because of who built it (the government) and how they have chosen to make that good available. This is a crucial point for thinking about why some goods end up being provided by the state instead of the private sector. Unless the private sector can determine a way to monetise creating a good, it will not provide it.

So in thinking about the consequences of who builds internet infrastructure, we have to consider both sides of the debate that unpack what things look like under each situation. So according to free market theorists, private businesses are better placed to leverage creativity and innovation in the provision of goods. That’s because the free market is more likely to respond to market signals. In short, price hikes will help cool demand and alleviate scarcity by efficiently rationing goods based on consumers’ ability to pay. If sellers take price hikes too far, customers will just go to a competitor across the street. I have many examples of how the market fails to deliver this beautiful outcome but that’s not the focus for today’s discussion.

One thing worth highlighting though, is that when the market comes in, user fees can exclude those who do not pay from accessing the good. So, even if infrastructure provision by the private sector might mean increased efficiency, there might be a resulting equity problem to contend with.

What does all of this have to do with Google and Equiano?

Quite a bit actually.

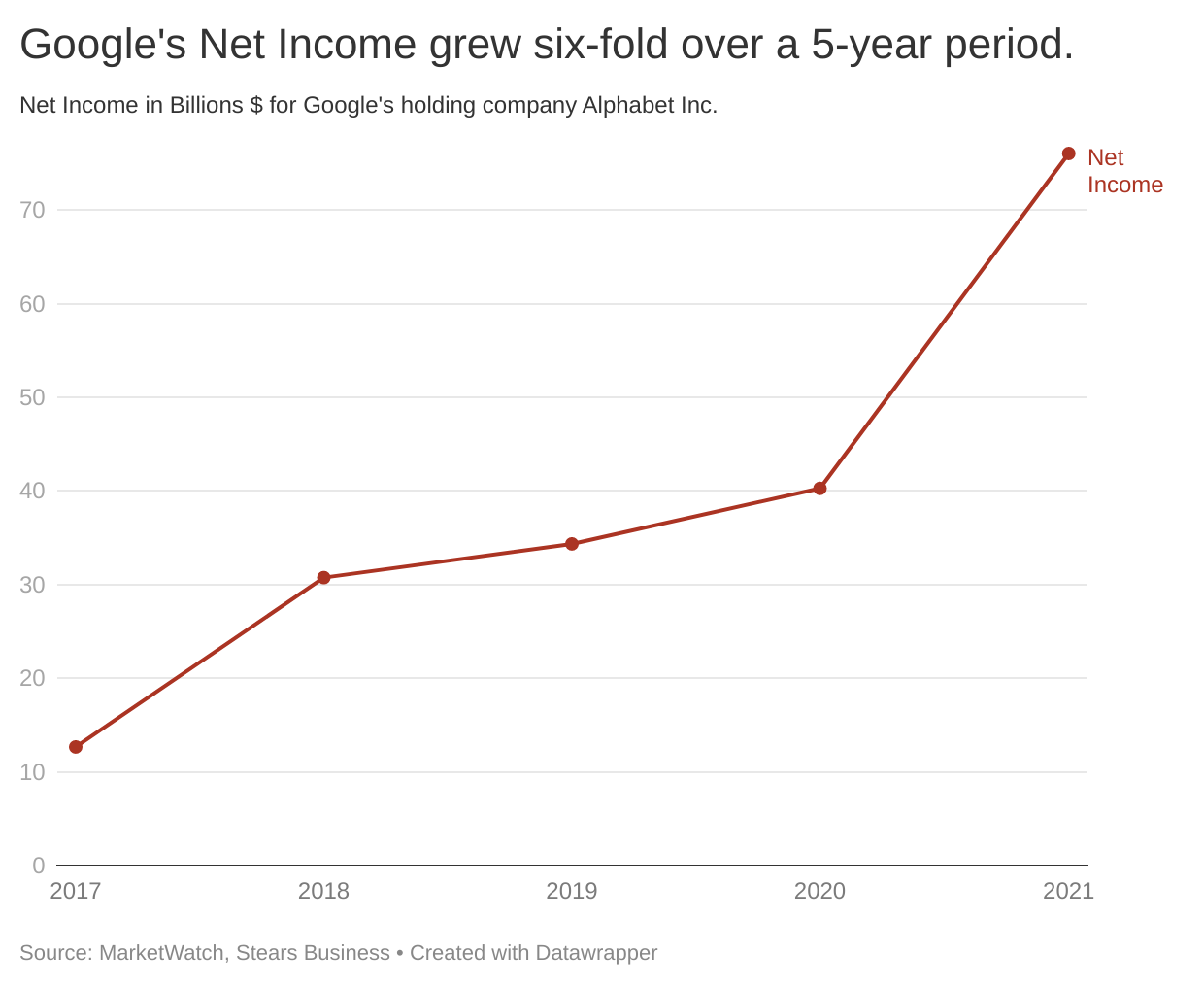

You see, Google is a private company, and ranks top of the list as one of the most profitable companies in the world. The Equiano cable system is the third private international cable owned by Google, and the 14th subsea cable invested by Google.

Being part of Google’s network undoubtedly has strong benefits. The most commonly referenced advantage is the potential for these subsea cables to deliver faster and cheaper internet. For example, back in 2013, following the arrival of MainOne’s cables, internet access was provided by as many as five undersea cables operated by different companies, including Globacom. Consequently, the multiple options for Internet Service Providers (ISPs) helped drive internet prices in Nigeria down by as much as 80%. In addition, the Equiano cable comes with 12 fibre pairs (most long distance undersea cables contain six or eight fibre-optic pairs) and according to Google, has a design capacity of 144 terabits per second, which is approximately 20 times more network capacity than the last cable built to serve the region.

However, as I have already explained, subsea cables are critical infrastructure because improved internet connectivity provides a platform for innovation, which is used as a key input across sectors, particularly the now budding digital economy. As has been documented previously, the digital economy is highly capable of creating unprecedented opportunities for countries to create jobs, new markets, and transform people’s lives. A noteworthy example of how this manifests includes the growing influence of fintechs, such as pure play agency banks like OPay and Paga that offer the unbanked population an alternative means of accessing financial services without needing a costly bank account. Innovations like these have put Nigeria on a path towards greater financial depth and inclusion.

As such, beyond the exclusionist challenges private companies present when delivering key infrastructure, there is the added complexity of security and potentially being subject to the whims of a foreign and private entity. To elaborate, not much stands in the way of Big Tech—the moniker attached to companies like Google. Even as the tech behemoths gain market power, not much has been done to curb their power. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, it was reported that Apple Pay and Google Pay stopped working for Russians as they attempted to use Moscow’s metro system. This resulted in Russian citizens experiencing problems (such as long queues) when attempting to pay fares using Apple’s and Google’s services.

Although public opinion is currently strongly in favour of any and all sanctions against Russia, it is worth noting that Big Tech companies such as Apple and Google were able to pull the rug from underneath millions of people in Russia instantaneously without being subject to due process. It is therefore incumbent on us to ensure that as we welcome innovation, we pay close attention to the terms, actively negotiate for adequate control and continue to develop contingencies.

What’s in it for Google?

Again, it is worth reiterating that Google is not supplying these subsea cables simply out of altruism. The process involves laying thousands of miles of cables along the seafloor and stretching between continents to carry internet around the world. Typically, investing in cable projects involves a consortium of other companies, who tend to be other operators in the internet provision space, looking to increase their own capacity. For example, data centre companies like the West Indian Ocean Cable Company or even telcos. To better visualise what Google stands to gain from investing in countries' digital infrastructure, think about the potential benefits like this:

Historically, Google and its other ad-driven competitor (Meta) have been trying to find ways to bypass existing infrastructure and introduce the internet to more people across the world, particularly those living in the Global South.

Back in 2011, Google launched Project Loon, a radical experiment that involved deploying high-speed internet in remote parts of the world using a fleet of balloons. According to Google, the tech giant has invested about $47 billion between 2016 and 2018, which has included investments to improve global internet infrastructure. Similarly, Meta has previously partnered with telco giant, Airtel, to launch free internet services in 17 African countries. Worth noting that Meta had to cancel this service after being criticised for being a “walled garden” version of the internet curated by Facebook. See what I mean about allowing private entities to build key infrastructure?

The incentive is clear. Both Meta and Google are on a quest to find their next billion users.

One of the primary ways that Alphabet—Google’s parent company—generates revenue is through advertising. For example, whenever you or I search for anything using Google’s search engine, an algorithm generates a list of search results. Once the search page comes up, you’ve probably noticed that in addition to what the Google algorithm has deemed most relevant to your query, some related suggested pages also show up from a Google Ads advertiser. Google generates fees from advertisers when users engage with the ad in some way, such as by clicking on it or by simply seeing the ad.

With up to 5 billion people using the internet today, it’s not surprising that in 2020, of the $183 billion Alphabet generated in revenue, over 80% of that ($147 billion) came from Google’s ads business. In essence, Google has been the market leader in online advertising over the last ten years, causing a massive disruption to other industries such as media publishers including Medium and The Economist.

Little is known about Google’s business model for Equiano, but it’s unlikely that the play here is to charge market prices for access to the undersea cables. That’s because Google has plans to make more money from advertisements than from the sale of international bandwidth to ISPs. Remember I said quality infrastructure begets cheaper internet service? With Equiano, Google can reduce latency, which is the time it takes for data to move between networks. This will save Google computing time, and will make it cheaper and more efficient for those of us connected to Google’s network to consume some of the data heavy services that Google provides. Think Google Meets. Youtube. Google Cloud. The list goes on.

I should repeat again that this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, particularly for those of us that increasingly need Google’s tools to complete daily tasks. What I’m drawing out here is that Equiano’s landing could mean that Google will come to have a significant stake in Africa’s internet, further expanding the tech behemoth’s growing reach.

It’s also worth remembering why the internet was conceived in the first place—to decentralise telecommunications and release consumers from the oligopolistic (when few players dominate the market) grip of telco operators. We have seen the internet make great strides with that. A recent example includes fintechs that are building a new iteration of mobile money services, which will unseat telcos’ dominance in the space. However, as a tech behemoth like Google increasingly owns a larger share of our undersea cables, we might find ourselves back where we started: a select group of companies controlling our internet activity and building the internet for their own use.

However, it won’t be such an easy win for Google. Already, the Nigerian market is being served by MainOne, Globacom and other companies who have connected Nigeria using undersea fibre optics cables. It’s also worth pointing out that Google plans to connect its undersea cable to a landing station in Lagos—the West Indian Ocean Cable Company is Google’s landing partner for Equiano and their facility is located on Elegushi beach in Victoria Island. About five other undersea cables that connect Nigeria arrive through Lagos. Thus, any catastrophic unforeseen event in Lagos could leave the entire country without internet access.

Regardless, we must remember that Google is set to provide a critical part of our infrastructure that allows us to connect to the rest of the world. Google’s ambitions have the potential to make our internet connectivity more robust. However, as the tech giant builds and owns global data links, the secondary consequences will mean a significant shift in how the internet works and who controls it.