According to the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF), Nigeria is set to borrow over ₦11 trillion next year to fund its budget deficit. That’s about 5% of our GDP—higher than the 3% threshold stated by the fiscal responsibility act of 2007.

There are no signs that the government will soon reduce its record-high borrowing trend. Even worse, the ministry of finance and the budget office have already budgeted to spend more on petrol subsidies than the government will earn.

Key takeaways:

-

Lending is an investment. And two things drive the investment market: fear and greed. To a large extent, the safety of sovereign assets reduces the risk of one losing their money, while greed informs why investors lend to emerging economies with high-risk assets.

- Rating agencies assess a country’s willingness and ability to meet debt obligations to measure the risk associated with lending to the country. Where the credit risk

With the above track record of borrowing and spending, it might be easy to conclude that investors and lenders will be unwilling to give the Nigerian government even more money. But the reality is far from that. While speaking about this in the Stears Newsroom, our finance analyst, Yomi, commented that "even with Nigeria's debt servicing ratio being more than 100%, when the FG issues a bond, it would still be oversubscribed (lenders were willing to invest more money than Nigeria requested)".

So that’s what I want us to focus on today. Why would any investor be willing to give Nigeria more money when it is clearly in fiscal distress?

Run for safety

The first thing we need to understand is that lending is an investment. I give you money for some time; you give me back at a later date with interest.

Also, two things drive the investment market—fear and greed. Fear; that they might lose their money and greed about the possibility of gaining as much income as possible.

Now, investors put their money in sovereign debt (debt to governments) because it’s highly unlikely that one will lose their funds through such investments. Losing one's funds is not impossible, but sovereign debt reduces the fear of investment risks.

Sovereigns are unlikely to run out of money because they can and will always charge taxes. But for many countries, especially resource-heavy countries, the government's earnings don't come from taxes alone but also through proceeds from mineral resources. This is why one of the critical features of loans from Chinese lenders, and many other commercial bilateral lenders, is the securitisation of the debt. The lenders protect themselves by requesting an asset or future income from their debtors’ mineral resources.

The possibility of receiving income from a country indefinitely (at least till the loan is repaid) significantly reduces the risk of losing the loans given to the country. This is why despite Sri Lanka's declaration of bankruptcy earlier in the year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has agreed to bail out the country with a $3 billion loan. Although this IMF loan comes with the condition that Sri Lanka's creditors provide debt relief on existing loans, the IMF is confident in getting its money back because Sri Lanka can earn income in the future. The country has shown this by announcing its plans to raise taxes to repay defaulting loans. Whether the country needs a tax increase now is a story for another day.

As a result, sovereign loans are "safe" assets because of the possibility of future liquidity, either from taxes or existing assets.

But even sovereign debt is not always safe, especially when the loan is owed to foreigners—through foreign bonds. These bonds, usually in foreign currency, become extremely difficult to repay when the borrower country runs out of foreign exchange. As such, there’s a high likelihood of default—the worst-case scenario for debtors. This year, Sri Lanka defaulted on its $51 billion debt (most of which is owed to foreign bondholders). What's worse is that the IMF requests debt relief on these funds, which means the creditors might never get their money back.

Of course, the borrower country also suffers from this outcome because they can lose access to the bond market, making it very difficult to borrow in the future. That’s the story of Greece back in 2008. Between 2008 and 2010, Greece owed loans worth about 15% of its GDP, defaulted on many loans, and its bonds were downgraded to junk status—that is, the loans have a high risk of default.

So, even though Nigeria is yet to default on its loans, its current fiscal situation, where it has to borrow not just to fund its expenses but also to pay back existing loans, should alert investors to a crisis looming. But they seem unfazed by Nigeria’s fiscal standing.

At the beginning of the year, when the Federal Government (FG) issued a Eurobond of $1 billion, although the interest rate was high, investors were still so interested that it was oversubscribed. What's the excuse for investors who rush after a bond issued by a country in fiscal distress?

Greed.

Big risk, big returns

Remember, two things drive the market: fear and greed. So, we've spoken about the first: fear. Investors typically go after sovereign bonds because they are relatively safer than other securities.

However, there are situations where all the signs point to fiscal distress, but investors still put their money in such countries.

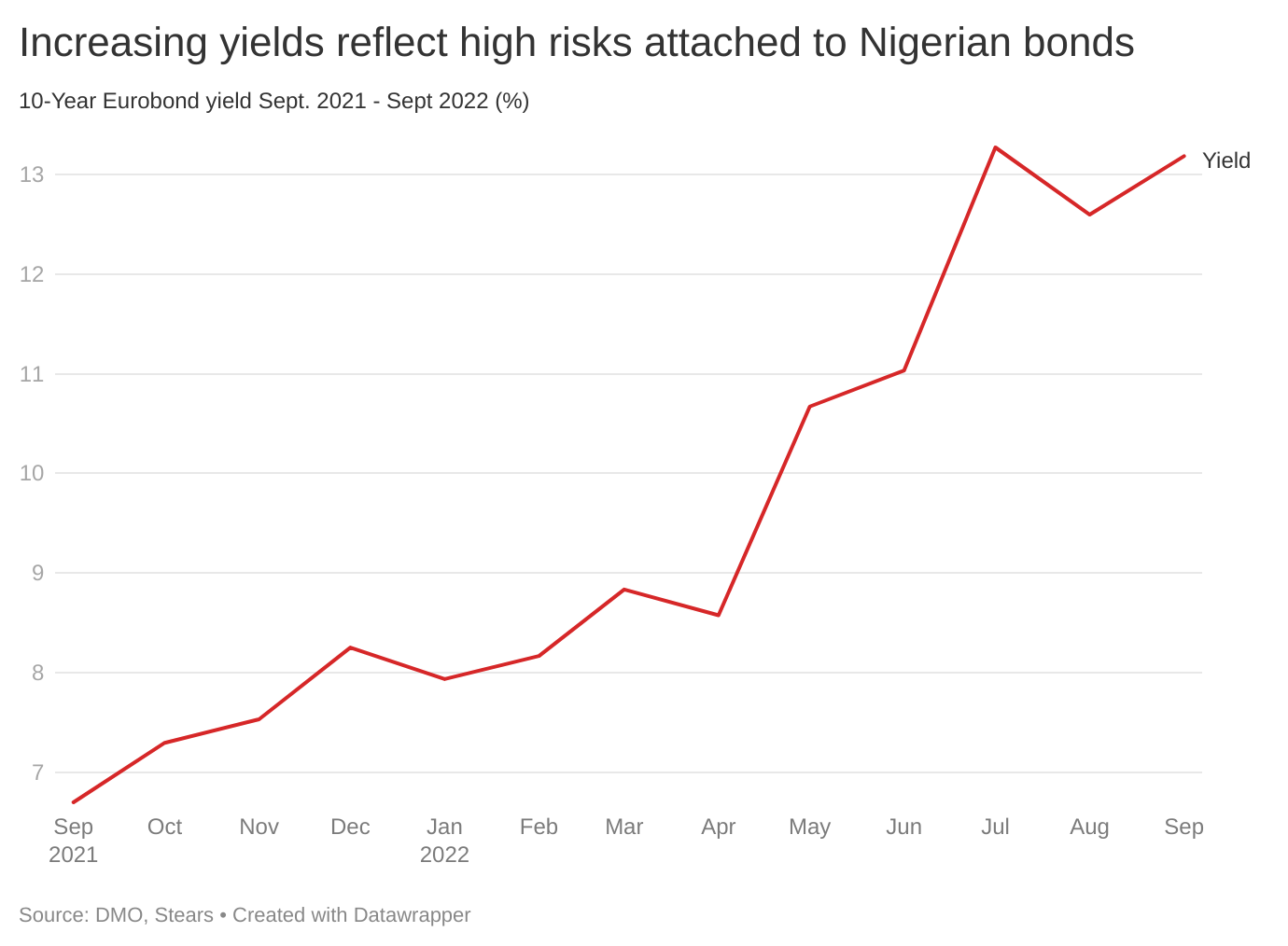

This is because of greed. Investors are willing to stake their money in high-risk investments if they believe they would churn out high returns. The higher the risk, the higher the return. So investors tend to request high interest on bonds from countries with a high risk of default. Investors understand that they might lose their money, so they charge higher for taking the risk. For instance, Nigeria’s 10-year Eurobond has an interest rate of 13.182% compared to the US’ 10-year bond with an interest rate of 3.28%, showing their level of risk.

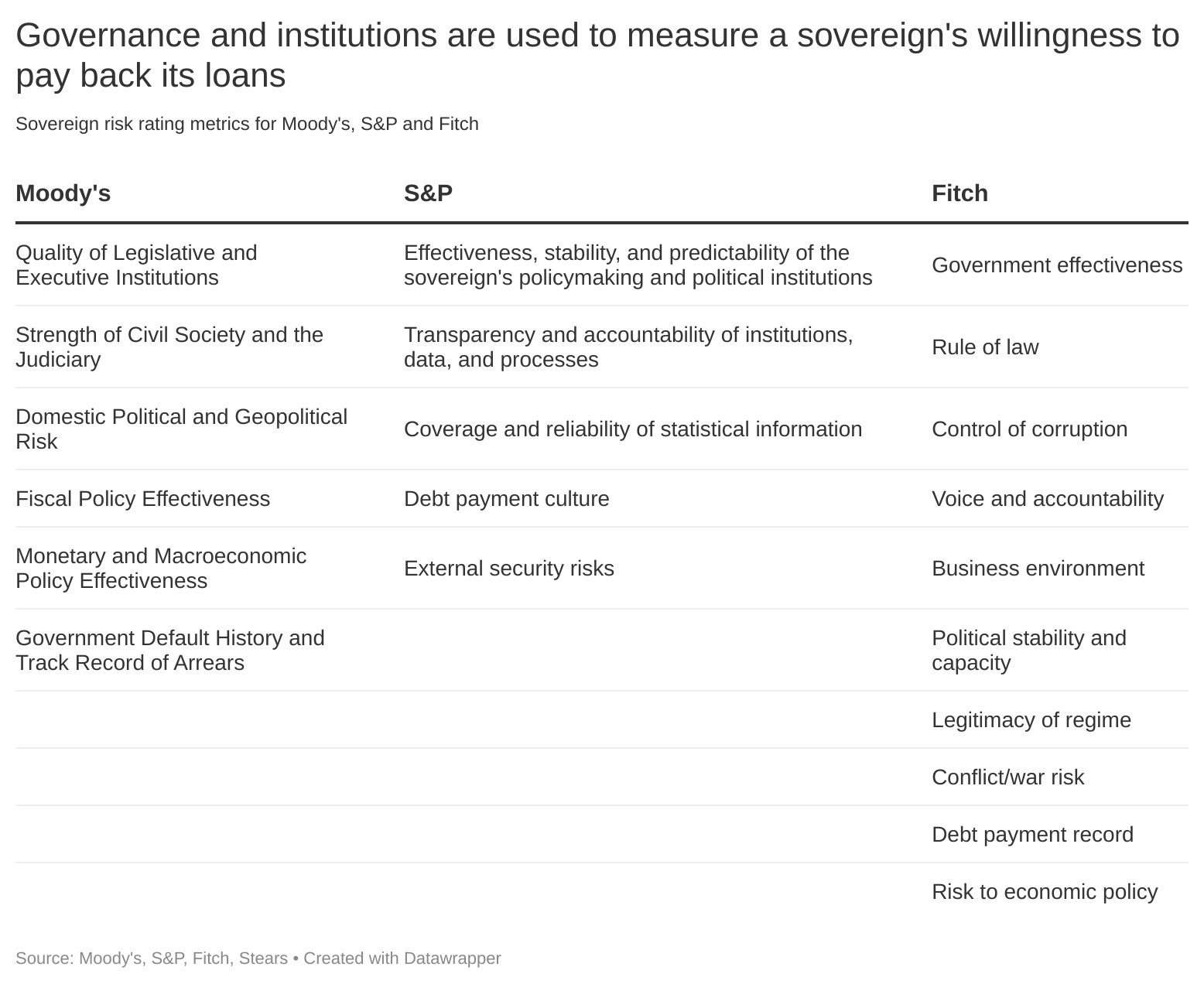

Every sovereign debt has some risk attached to it. Sovereign risk is when a country is unwilling or unable to meet its debt obligations. This risk is typically informed by credit risk ratings from agencies such as Moody's, Standard & Poor (S&P)'s and Fitch's rankings. Just like the definition, the agencies attempt to measure two things: the country's willingness and ability to pay back loans.

The willingness is measured by the country's political landscape and institutions. A country's political tenure—who is in power and how the person got there, goes a long way in determining how the country's funds are used. Also, the institutions that guide how the law in each country is enforced inform how the government's funds are used and what fiscal actions the government takes. Institutions, in this case, refer to the strength of a country's judiciary, its fiscal transparency, and how well the country upholds contracts and enforces punishment for failure. For instance, we explained how countries with weak institutions are prone to have more questionable loan terms than countries with strong institutions.

An example of unwillingness to meet debt obligations was when Gen. Abacha stopped servicing Nigeria's Paris club debt between 1993 and 1998 as retaliation for sanctions against Nigeria for human rights violations. The non-payment led to Nigeria accumulating $4 billion in late payment fees and debt payment arrears. A more recent example of willingness to pay (or the lack of) is the NNPC’s cash call arrears of over $4 billion, which it owed to oil companies from 2016. In July, the company repaid most of the debt but still has over $600 million left to pay. Likewise, the federal government currently owes over $500 million in promissory notes to local contractors.

When the country purposely refuses to pay its debt obligations, investors or lenders would only lend money to the country if they are sure that the returns on the loans are high enough to warrant the risk. The risk here is giving your money to a country without the possibility of getting it back.

The other thing these rating agencies look out for is the country's ability to pay back. This has more to do with what makes up the country's GDP and the government's ability to generate income to pay back its loans. The rating companies look at the country's economic strength, external assessment, and fiscal and monetary policies.

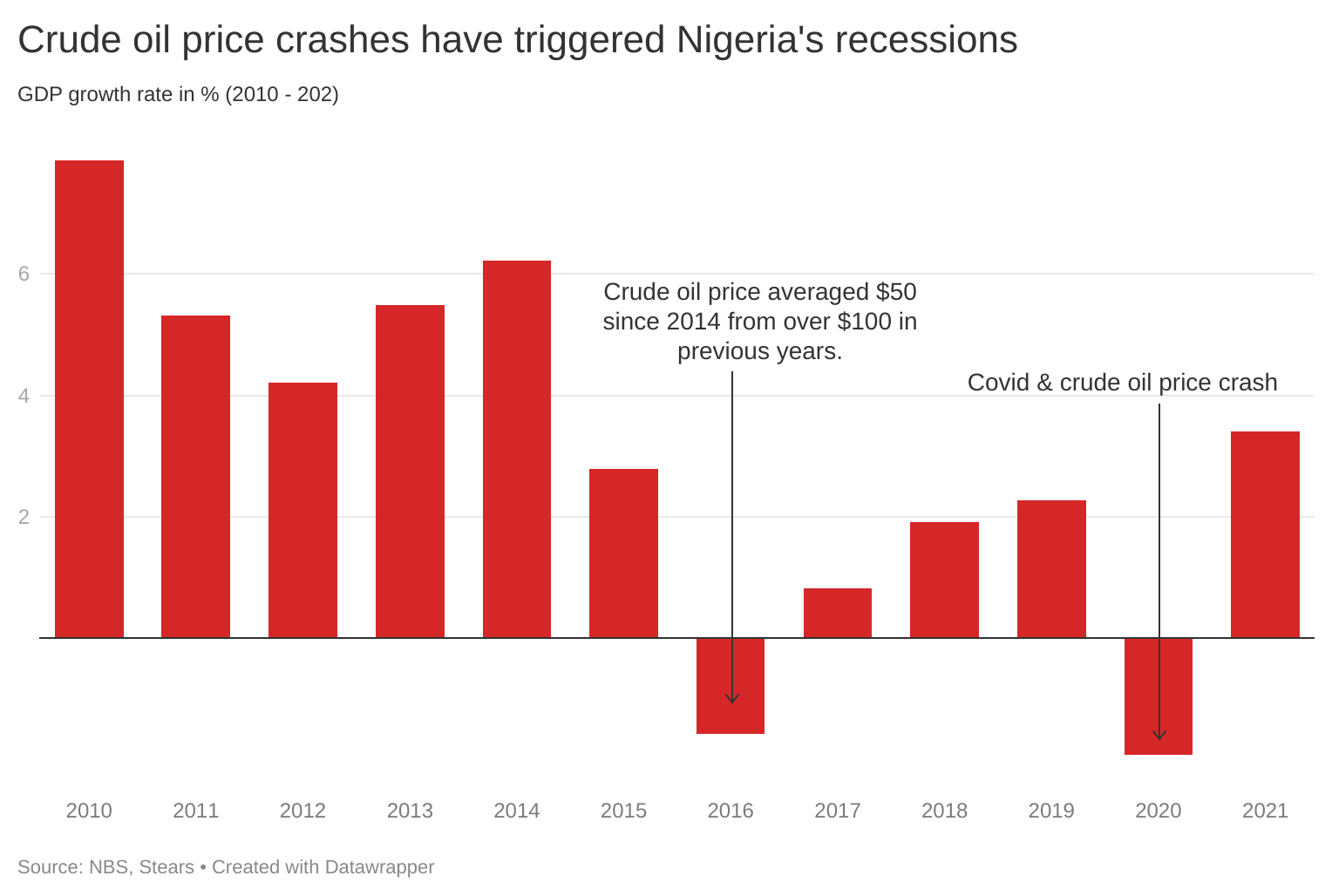

Economic strength encompasses the country's GDP growth, the economy's key sectors, and how volatile they are. Remember that a sovereign asset's safety depends on how much the country can tax in the future. These taxes come from the GDP. The larger the economy grows, the more likely the government is to impose the taxes it will use to pay back its loans. For a country like Nigeria, whose tax revenue is much lower than its crude oil revenue, the rating companies look at other income sources and the GDP.

This is where metrics like volatility come in; how volatile is the income source? Nigeria's income from crude oil is highly volatile. Whenever there's a sudden sharp drop in crude oil prices, even though crude oil exploration makes up about 7% of the GDP, the country enters into a recession. This threatens the country's revenue from crude oil and its tax potential.

Also, countries that rely on sectors like tourism are highly susceptible to liquidity risks, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic. This is because without sufficient foreign income coming into these countries, the country would have a liquidity constraint and struggle to pay its foreign debt—a risk for the investors. Liquidity constraint is why the airlines are still struggling to get their money out, which has been a risk for Nigeria. This began in 2020 when the CBN had a huge backlog of investors waiting to take their money out of the country; it has only worsened.

In the S&P's 2022 credit risk ratings outlook for Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) 's emerging markets, it anticipated that Nigeria's credit risk rating would worsen. The report stated, "We could lower the ratings if we saw increasing risks to Nigeria's capacity to repay commercial obligations, either because of declining external liquidity or a continued reduction in fiscal flexibility. This could occur, for instance, if we see significantly higher fiscal deficits, debt-servicing needs, and significantly reduced foreign exchange reserves."

So, when investors weigh the risks associated with lending, their response is usually higher interest rates for high-risk and low-interest rates for low-risk investments.

How risky are Nigeria's bonds?

One way to see how Nigeria is doing in investors' portfolios is to look at how well the country has been able to raise money recently. Earlier in the year, the country raised a $1 billion Eurobond at a rate higher than it raised a $4 billion bond in 2020. Likewise, the yield on existing Eurobonds has been increasing all year. This happens when investors believe your sovereign debt is risky—they attach high interest rates.

This points to lenders attaching more risk to Nigerian assets, existing and new. Investors are acting like this because of the perception of risk attached to the Nigerian economy. First, as I’ve repeatedly mentioned, our debt servicing to revenue ratio is over 100%. Also, the government is making little to no effort to change this. In the budget for 2023, the amounts the government budgeted for fuel subsidy (₦6.7 trillion) and debt servicing (₦6.4 trillion) are higher than the expected revenue (₦6.3 trillion).

So, next year, after fuel subsidies have been removed, the government will only earn ₦370 billion from crude oil and spend the rest of its income servicing its debt. The rest of the budget (including salaries) would need to come from new loans.

The 2023 budget indicates to investors that Nigeria has a dire liquidity and solvency problem. When government revenue is constrained, it pulls the economy down, which means the potential for earning money from taxes will also be squeezed.

With most of the government's revenue going to fuel subsidy payments and debt servicing, it is unlikely that our forex liquidity problems will be solved. So, willingness to meet debt obligations is unlikely to improve, as the government will struggle to meet its debt obligations to its contractors.

In May, JP Morgan advised its investors not to be overweight in Nigerian bonds, holding fewer Nigerian bonds in their investment portfolio.

So, how risky are Nigerian bonds? Highly risky.

Sweet crude turning sour

Will lenders continue to give us money? Most likely.

Why? Because of oil. Despite all the above-listed fiscal issues, Nigeria still has the 10th largest crude oil reserves globally. The country's potential income from crude oil would be nothing compared to what we owe if we extracted all the crude oil today.

So, bondholders know that Nigeria has enormous revenue potential. Even if they were to stop lending to Nigeria today, Nigeria could still get funding from bilateral loans because the bilateral partners can request for the loans to be securitised. We can give the lenders future income from crude in place of loans today.

But even this crude oil is no longer Nigeria's golden egg because the government is not earning as much as it should from its crude oil sales because of oil theft and the resultant pipeline shut-ins. Despite having the capacity to produce 2 million barrels per day (mmbpd), we’re currently at a capacity of 1.084 mmbpd. Some months ago, the Nigerian government shut down the Trans Niger Pipeline (TNP), responsible for transporting about 10% of Nigeria’s crude, because of oil theft.

So, if the government were to securitise its loans, the lender would have to take partial ownership of the oil rigs to get what is due to them.

While mineral resources give countries like Nigeria an edge in investors' books, the country must ensure that even the resources are still viable to investors. Currently, Nigeria's oil sector has not been very attractive, with the likes of Shell and ExxonMobil divesting from onshore assets out of the country still due to this problem of oil theft and disruption to their operations. These make lending to Nigeria difficult.

Lending is first an investment before anything else. And lenders think of the loans they give out as assets. Every investor wants a healthy risk mix in its portfolio, which is achieved by frequently reducing its high-risk holdings and replacing them with medium to low-risk assets.

Nigerian bonds remain a high-risk asset on the two fronts of willingness and ability to pay back loans. Enhancing the metrics that reduce Nigeria’s credit risks—showing investors that you’re willing to pay back by meeting the smaller and more local debt obligations—will improve things.

Then, the government will need to revamp the economy's outlook by attracting foreign investment and boosting its revenue capacity to attract investment and reduce debt reliance. Steps to improving this would be solving the problem of oil theft to restore investor confidence. With more revenue (and fx) coming in from crude oil sales, we can earn more fx to meet our debt obligations and serve as a reliable means of securitising our debt.

Without putting these measures in place, the Nigerian government will get to a point where investors will go from increasing the interest on Nigeria’s bonds to refusing to lend to Nigeria altogether. At that point, oil won’t save us.