We are entering a new economic era.

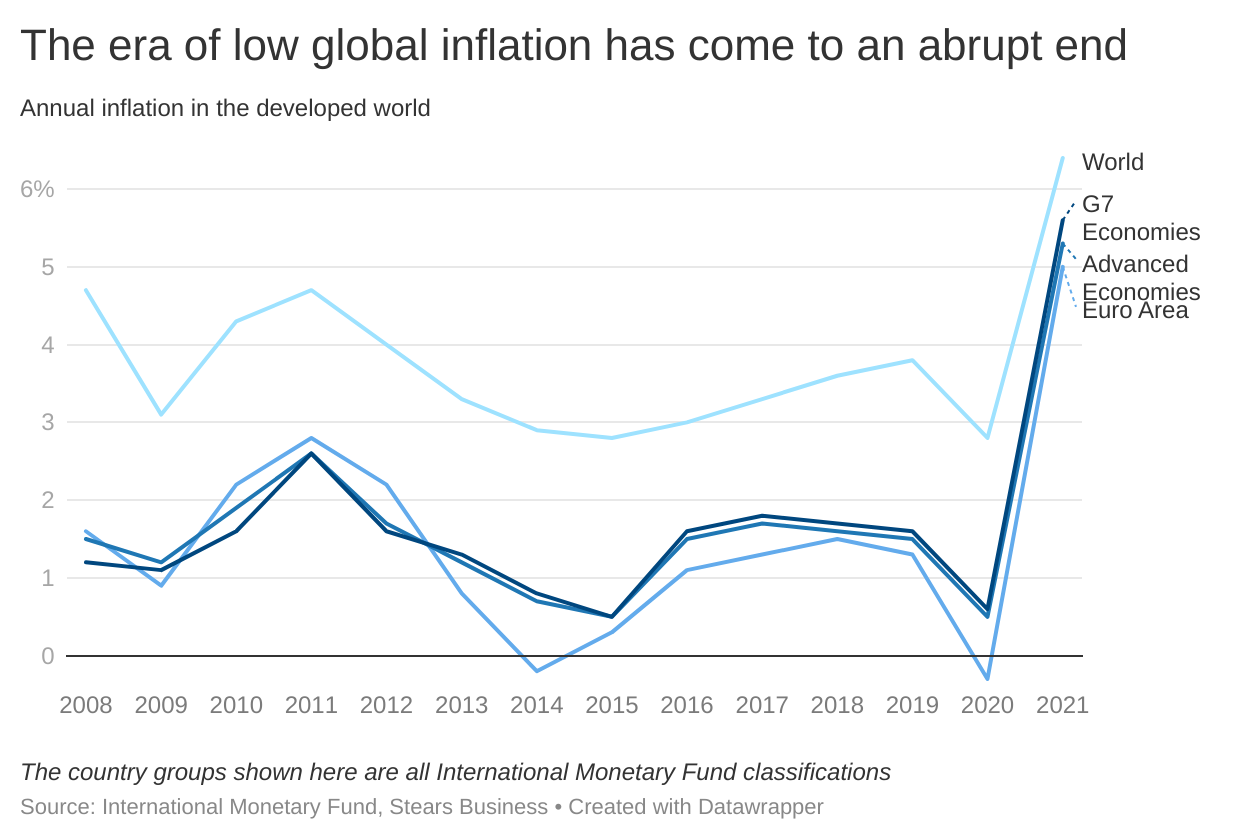

A few weeks ago, we flagged how historically high inflation in the United States and other developed countries is affecting the global economy. After the last global recession (2007 – 2009), central banks in the developed world took centre stage, pursuing a complex and innovative quantitative easing (QE) policy to reflate the global economy.

Key takeaways

-

We are in a new dispensation of monetary policy, and Nigeria is not exempt. After the CBN pursued a relatively low-interest rate regime for over five years, it finally increased its anchor rate (MPR) to 13% to curb inflationary pressures in the country.

-

The change in interest rates is significant to the Nigerian economy because they determine the direction of several indicators, including savings, borrowing costs, consumer disposable income, investment inflows and GDP growth.

- But the ability of the rate hike to reflate the economy depends on

By and large, QE worked. The global economy picked up again, notwithstanding ad hoc shocks like the pandemic and Brexit, and QE never led to rapid inflation as previously feared. In fact, for nigh on a decade, the global economy enjoyed a period of ultra-low inflation, even with central banks flooding financial markets with trillions of dollars of new money.

The era of low inflation, low interest rates, and loose monetary policy is over for the global economy.

And for Nigeria, too.

Ironically, even as its inflation trend diverged from developed economies, Nigeria has pursued a relatively dovish—low interest rates—monetary policy regime for the last 5+ years.

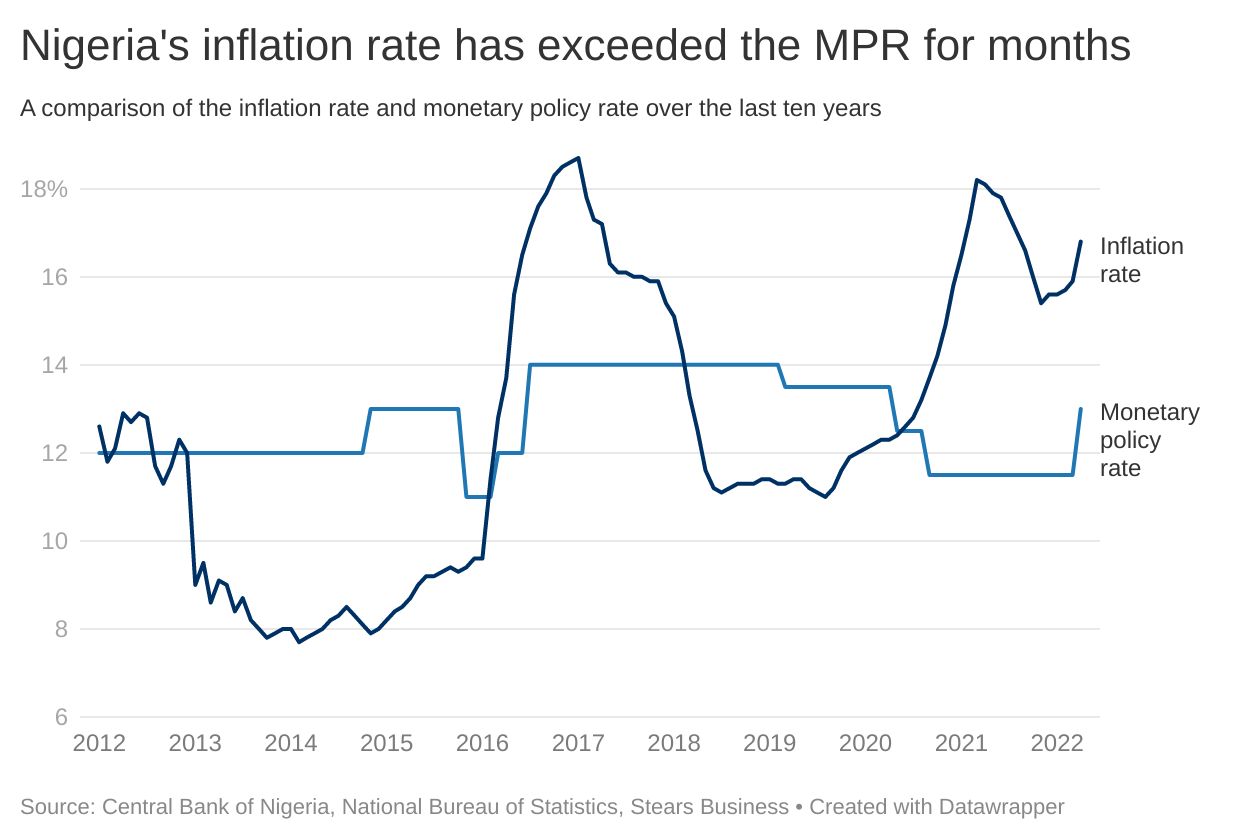

Here’s a chart showing Nigeria’s annual inflation rate and its monetary policy rate (MPR), the baseline interest rate in the country. It shows us the relationship between inflation and interest rates in Nigeria over time.

There are at least three things to notice in the chart. The first is how often and by how much inflation has run ahead of the MPR recently. The second is how infrequently the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) monetary policy decision-making committee—the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC)—alters the MPR.

The third is the data point for May 2022. If you haven’t heard by now, the CBN raised Nigeria’s MPR from 11.5% to 13% last week and hinted at more rate hikes, essentially ending Nigeria’s low interest rate era, just like the Federal Reserve is doing in the United States.

Increasing a country’s interest rates shouldn’t be a big deal. Nigeria’s MPC meets every other month to determine if rates should be changed, so we have at least five occasions each year to change the interest rate.

As we’ve pointed out already though, increasing the MPR has not been a common occurrence in our recent economic era. Or generally, even.

The recent rate hike is Nigeria’s first in nearly six years. The last hike was in 2016, when a near-collapse of the country’s exchange rate regime forced the CBN to take drastic action. They increased the MPR from 11% to 13% in six months and officially devalued the currency while also “liberating” the exchange rate. It was a Hail Mary move at the peak of Nigeria’s foreign exchange (FX) crisis and recession, and arguably the worst economic year in the country’s democratic history (ignoring 2020 because of the pandemic).

Apart from 2016, the MPC had only increased the MPR once in the last ten years: November 2014, from 12% to 13% after global oil prices plummeted and Nigeria’s FX woes began. Going back fifteen years to 2007, the only other time the MPC changed the base interest was when it did so four times between 2007 and 2008, eventually hiking from 8% in October 2007 to 10.25% in June 2008. Even at that time, no individual rate hike was by more than a single percentage point.

All of this is to say that last week’s MPR hike was relatively unprecedented and, just like 2007 and 2016, may mark the start of a new economic cycle in Nigeria. In his statement after the MPC meeting, CBN Governor Godwin Emefiele echoed this sentiment, explaining, “[The] MPC decided on the need to take a shift from its historically cautious approach on interest rate, to a policy rate hike…”

So, after a decade of low global interest rates, central banks all over the world have become hawkish amid significant inflation fears. And after ten years of relative inactivity (the MPR only changed eight times in ten years) and largely dovish monetary policy (despite high inflation), Nigeria’s CBN also looks to be entering an era of monetary tightening.

Now more than ever, we should explore whether higher interest rates make sense for Nigeria.

Why interest rates matter

Before we look at the arguments for and against higher interest rates, it’s helpful to remember why they matter. Here are the main reasons:

-

They determine the cost of borrowing and the returns on savings. Higher interest rates generally redistribute wealth from borrowers to savers.

-

They increase or reduce individuals’ disposable income. Lower interest rates reduce borrowers’ debt burdens and make it easier for them to spend.

-

They influence the level of real investment in a country. Interest rates are the cost of investing today—lower interest rates make it cheaper to invest in construction, manufacturing, expansion, etc.

-

They attract or dissuade (short-term) foreign investment. When interest rates are high, foreign investors are more willing to invest in high-yielding fixed income securities like government bonds.

-

They affect the exchange rate through foreign investment. Higher interest rates mean more foreign portfolio inflows and a stronger currency.

All these are true for Nigeria too. Interest rates are arguably one of the five or so most important economic policy levers that a country can use. They affect GDP growth, inflation, employment, international trade, investment, and more. History shows us that just by altering interest rates, central bankers can induce recessions and other adverse economic events. Most famously, the US Federal Reserve was blamed for its role in stoking high inflation in the early 1970s because President Nixon pressured the apex bank to lower interest rates and then for its decision to aggressively increase interest rates to rein in inflation, eventually contributing to the early 1980s recession.

That’s in the United States; you need no reminder about how powerful the CBN is in Nigeria.

Therefore, this discussion—and last week’s MPC meeting—is hugely significant for every Nigerian. We’re talking about what our economy may look like for the next ten years, regardless of who becomes President in 2023 (pending a change in MPC members, who are usually either CBN directors or renowned independent economists like Dr Doyin Salami, who served on the MPC from 2010 to 2017).

The case against higher interest rates

We have seen that the global economic era is changing from low inflation and low interest rates to higher inflation and higher interest rates. We have seen that Nigeria is also moving from a low interest rate era to a high interest rate era. We have seen why interest rates are so important.

Now, we look at whether the MPC should be raising rates.

Our analysis is inflation-consequentialist, i.e., what the CBN should do with interest rates is based on what will have the most positive impact on inflation, the CBN’s primary mandate. We will focus mainly on inflation as Emefiele recently railed at “the perception that the CBN has abandoned its primary mandate of taming inflation”.

Usually, this would be a simple question to answer. Basic economic theory tells us that interest rates and inflation are inversely related so increasing the MPR should reduce inflation. To understand why, think through how higher interest rates would affect any of the five reasons we provided earlier for why interest rates matter.

Basic economic theory comes with a caveat here: it depends on the type of inflation you face. Higher interest rates are great at curbing demand-pull inflation, where the problem is too much money chasing too few goods, and can effectively deal with imported inflation, where currency depreciation leads to higher domestic prices. High interest rates are also very effective at dealing with monetary inflation, the type you get from printing too much money too quickly.

Interest rates are less effective when inflation is cost-push or more generally, driven by supply and production reasons. Think about it—how will interest rates help when the government closes the land border and rice becomes scarcer? Or when the price of diesel doubles in a month?

Therefore, whether the CBN should be raising interest rates is primarily a question of what type of inflation Nigeria has and how it can be solved.

What causes Nigeria’s inflation

The most honest answer is that Nigeria’s inflation is a mix of all the types we highlighted. Furthermore, there is a lot of disagreement—even now—about the true causes of Nigeria’s inflation.

In his post-rate-hike statement, Emefiele yo-yoed when it came to the causes of Nigeria’s inflation. On the one hand, he admitted that it’s largely cost-push and structural, blaming higher energy prices and bottlenecks in food production for recent increases in inflation. On the other hand, in direct defence of the MPC’s decision to increase the MPR, Emefiele argued in favour of the other causes of inflation. “While the MPC identified several supply-side factors which may be contributing to inflationary pressure, emerging evidence shows that money demand pressure is on the rise and is unlikely to abate until the 2023 general elections are concluded.”

My harsh assessment is that Emefiele’s argument falls victim to choice-supportive bias and the MPC probably worked backwards from agreeing on a rate hike (for reasons we will see later) and then outlined the most convincing justifications.

The data supports this assessment.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) provides inflation data in Nigeria through the Consumer Price Index. The NBS tracks the prices of a fixed set of goods & services over time to compute inflation. This means that we can disaggregate inflation by product category to see what is causing it.

The biggest component of Nigeria’s CPI basket and Nigeria’s biggest inflation problem for the last decade is food inflation. Nigeria’s latest headline inflation figure is 16.8%. However, food inflation alone is 18.4% (non-food or core inflation is 14.2%). In 2021, headline inflation averaged 17%, while food inflation averaged 20%. If we look at the current month-on-month increase in food prices (roughly 2%), it will only take three years for average food prices to double in Nigeria and five years to triple. We know that Nigeria’s inflation is mainly a problem of rising food prices. But what causes this?

The data can help us here as the NBS breaks down food prices. We have the overall food inflation figure and a specific figure for imported food inflation. The bad news is that despite all the concerns about rising global food prices, Nigeria can’t blame anyone else for our food price woes. Imported food inflation (17.7%) is lower than overall food inflation (18.4%) and has been for a while. When you look at the monthly increase in prices, domestic food prices have risen faster than imported food prices.

Here's what we have learnt so far: Nigeria’s inflation is predominantly a food inflation problem, but we can’t use the data to trace what is driving food prices. We need to turn to agriculture and food production experts for answers here. But anyone familiar with Nigerian agriculture or food production will tell you that the issues are rarely demand related as we have many mouths to feed and even the poorest Nigerians spend nearly all their income on food. Instead, Nigerian agriculture is hampered by supply bottlenecks, from legacy issues like poor transport and storage infrastructure to policy mishaps like border closures and erratic FX policy. None of these (except the FX policy) can be addressed by the CBN or interest rates, so the case for higher interest rates is weaker.

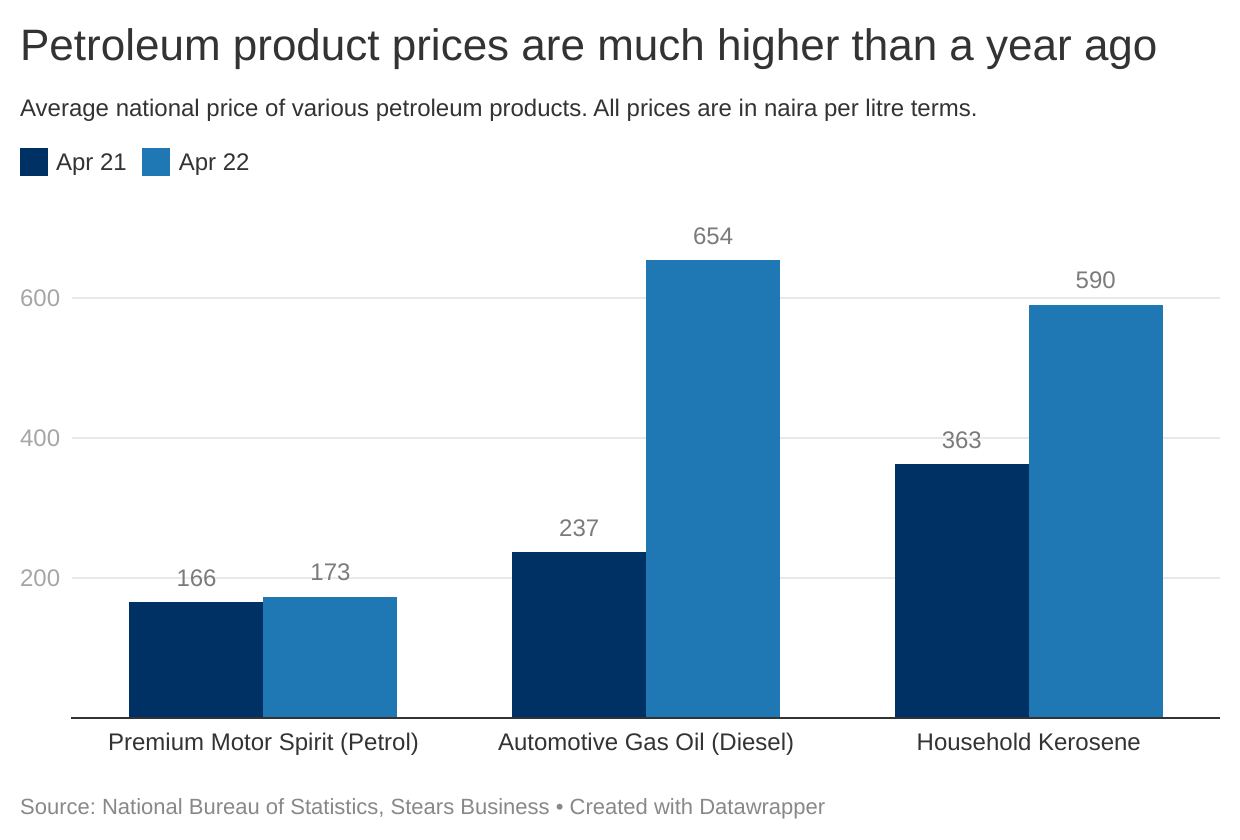

The other supply-side issue Emefiele blamed was energy prices. Energy prices are interesting because the lived experiences and the CPI tell different stories. We know that energy prices are much higher year-on-year. Anyone who pays for electricity or any fuel will attest to this. The data does too. The chart below compares the price of key fuels in Nigeria in April 2022 to their April 2021 value. Everything is up.

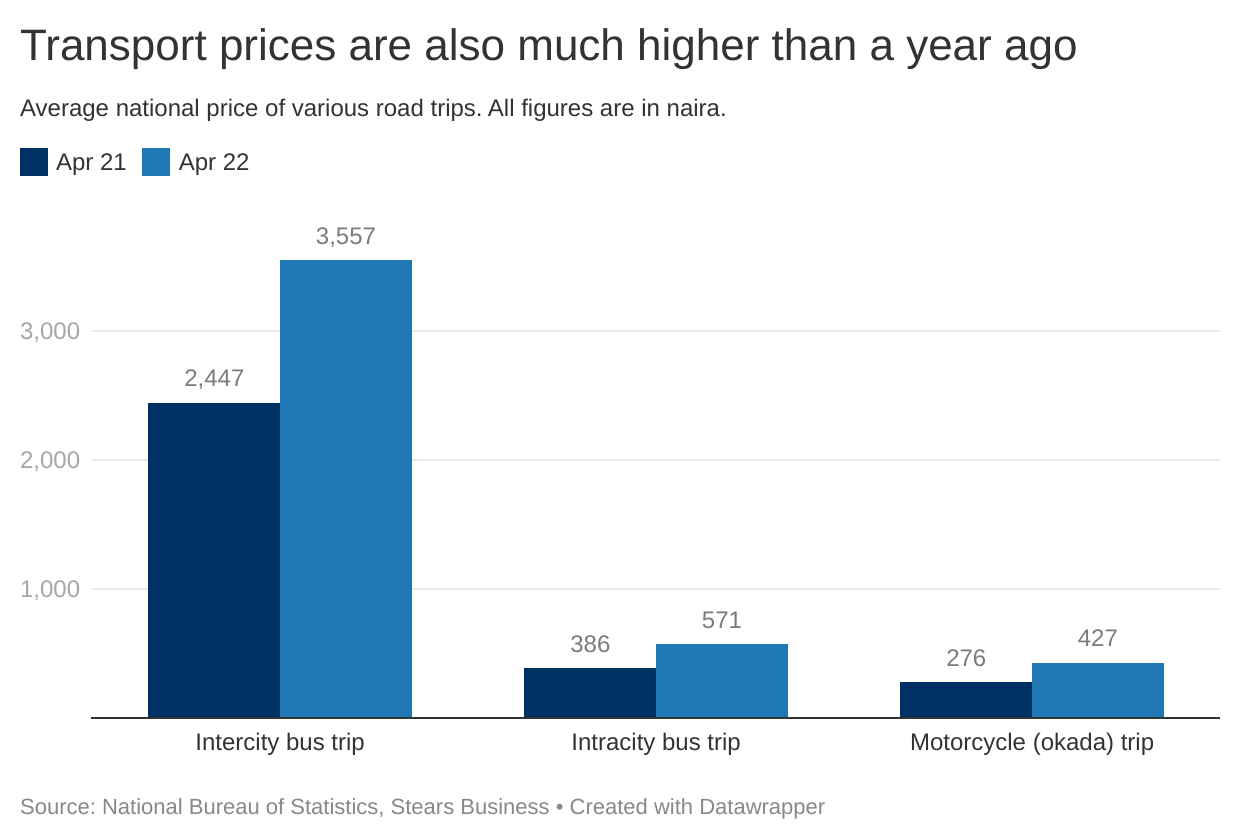

Unsurprisingly, higher fuel prices have filtered through to transport costs. This chart shows the change in average national transport fares for various modes of transport. Again, everything is up.

The problem here is that none of this helps us figure out how much of Nigeria’s inflation is driven by energy prices. How do we translate a 45% increase in average bus fares to the overall inflation rate?

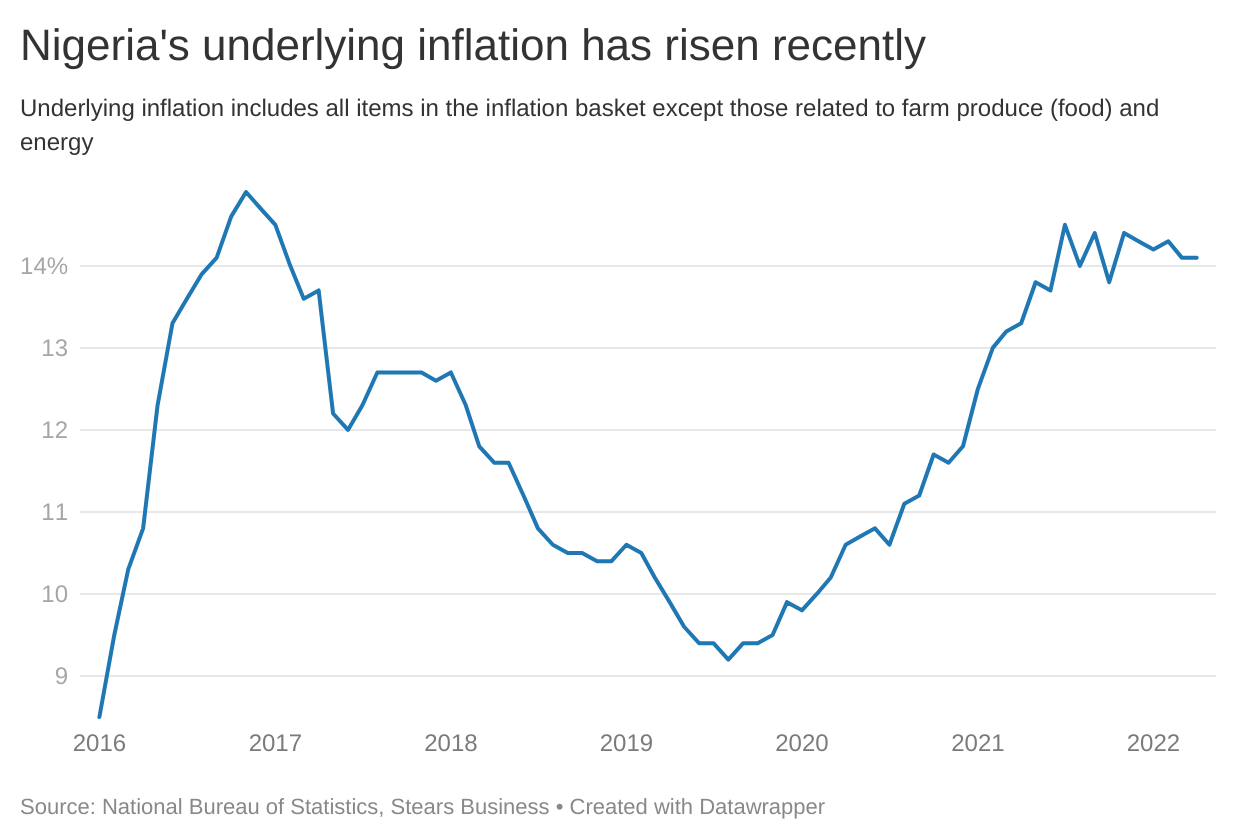

The NBS does not publish energy inflation, so the best gauge we have is comparing core (non-food) inflation to core minus energy. We will call the latter "underlying inflation" as it strips out food and energy prices, which are often very volatile and will not always reflect underlying economic conditions. The problem is that there is barely any difference between the published figures for core inflation (which includes energy prices) and underlying inflation (which doesn’t). If you compute the correlation between core and underlying inflation from 2016 to date, you get 0.88. This means that even when we see (and experience) large swings in energy prices, it’s hard to trace the effect in the CPI numbers. To compound this problem, we know that energy prices also affect the prices of almost every other product, via transport and production—especially true in a country where most transport and production activities are powered by petrol and diesel. This is a critical point as the CBN’s decisions are based on CPI estimates and not anyone’s lived experiences. Although the MPC knows that energy prices are worsening Nigeria’s inflation, it is doubtful that they know by how much.

For us, it makes it harder to conclude that Nigeria’s inflation is driven by energy prices. The data just isn’t there.

The case for higher interest rates

The data can help us make a case to support the rate hike.

Let’s go back to underlying inflation (no food and energy prices). Underlying inflation was 14.1% in April, lower than headline (16.8%) and food (18.4%) inflation. When you remember that some of this underlying inflation is capturing the indirect effect of higher energy prices, Nigeria’s inflation picture looks less bleak.

Furthermore, underlying inflation has barely changed this year, compared to other prices. In the first four months of 2022, the average month-on-month rise in underlying prices has been 1.1%. In 2021, the average month-on-month rise in underlying prices was 1.1%. Again, this makes sense. Remember, we strip out most of the recent shocks to food and energy prices (global & local) when looking at underlying inflation.

In contrast, in the first four months of 2022, the average month-on-month rise in aggregate prices in the economy has been 1.7% (so prices have risen roughly 1.7% each month). In 2021, that average was 1.2%. Although these figures look similar, they have very different effects over time. It would take an extra eighteen months for prices to double if we had 1.2% monthly inflation compared to 1.7%. When it comes to percentages, little differences compound over time.

The summary is that Nigeria’s underlying inflation picture doesn’t look like it has changed much. If the MPC wasn’t worried about inflation this time last year, why should it worry now, when inflation is mainly driven by energy and food prices?

But this is a classic case of when numbers lie. If we look at the numbers another way, we will see that underlying inflation is rising after all and is a legitimate concern.

The chart above makes the perfect case for the CBN. Two years ago, in April 2020, underlying inflation was 10.6%; now, it’s 14.1%. An argument can be made that the CBN has responded too slowly, and they should have raised rates sometime around late-2020 or early 2021 when underlying inflation began to spike.

Looking at this data, we can only conclude that there are genuine underlying inflation pressures in Nigeria outside energy prices and food prices, and these have been around for a few years at least. The challenge is figuring out the cause. Unfortunately, drilling further into the NBS inflation data will not help us here. The truth is that very few people can make a coherent argument for what is causing this inflation.

The verdict

Data challenges notwithstanding, we have seen that Nigeria’s main inflation drivers are energy and food prices (currency depreciation and imported inflation are significant too, but that’s a story for another day). These are not issues that can be solved by increasing interest rates.

However, we have also seen that there are underlying inflation pressures that higher interest rates may tackle, but we don’t know for sure. And chances are, neither does the CBN.

Where does all of this leave us? You could make a case for higher interest rates, but most judges would rule against you, looking at the available data.

It is possible—likely, even—that the CBN has not used the same inflation-consequentialist framework we have used here. Despite the Governor’s reminder that price stability is the bank’s core mandate, the interest rate hike is more justifiable if you optimise for more than just price stability.

The CBN’s game looks similar to 2016. As global interest rates rise, Nigeria’s rates need to increase as well for our investment climate to remain competitive. Traders & investors shop around for the highest interest rates they can get on their short investments. This group (foreign portfolio investors) is an important source of foreign exchange for Nigeria.

Emefiele may have shown his hand here as the final paragraph of the MPC’s considerations for their decision echoed this view. “[The] MPC feels that tightening would narrow the negative real interest rate margin, improve market sentiment and restore investor confidence. Equally, members believe tightening would moderate inflationary pressure pass-through to exchange rate depreciation and moderate the speed of capital flow reversal, provide incentives for foreign capital inflows and sustain remittances.”

This argument is more convincing (who wouldn’t want more foreign investment and a more stable naira?). But I suspect that we are shutting the stables long after the horse has bolted. Stears has covered foreign investment in Nigeria previously. It’s hard to see a two percentage point increase in treasury bills enticing foreign investors who are not sure they will be able to remit their returns when they want to in the lead up to an election year. It looks a lot like putting a plaster over a gunshot wound.

Alas, the victim has been shot, and something must be done. The CBN has signalled its intent to fight inflation in Nigeria, a signal that could make a legitimate difference in shaping investor sentiment and inflation expectations—remember, this is a long-term determinant of inflation.

The CBN may need this signal to work because the data tells us that increasing interest rates will not make a material dent in Nigeria’s inflation.