The Nigerian government's current revenue position needs serious attention. Just last week, the Stears newsroom published a fascinating thread on Twitter setting out our challenges with revenue. The lowdown: we can no longer call Nigeria an oil-based economy (a sector that was previously a significant revenue earner).

In the recently revised 2022 fiscal framework, the Senate Finance Committee revised our oil production estimate to 1.6 million barrels per day from 1.88 million barrels per day. Sadly, this decline in revenue is happening at the same time that the government's spending has ballooned to an estimated ₦17.13 trillion as subsidy payments rose from ₦443 billion to a whopping ₦4 trillion, effectively widening the budget deficit to ₦7.35trn from ₦6.25trn (3.99% of GDP).

Key Takeaways

-

The drastic reduction in oil revenue has made it imperative for the government to hasten its steps toward increasing revenue from non-oil sources.

- Cocoa is an excellent

The recurring revenue problem has emphasised the need for the federal government to diversify its income base. This unsurprisingly involves considering other non-oil income sources, including agricultural commodities and taxes. We know from the latest fiscal framework that the government has plans to increase non-oil revenue from ₦2.2 trillion to ₦2.6 trillion.

Previous articles have extensively covered the government's approach to raising money from taxes. So today, I want us to look at the other potential source of revenue—agricultural commodities.

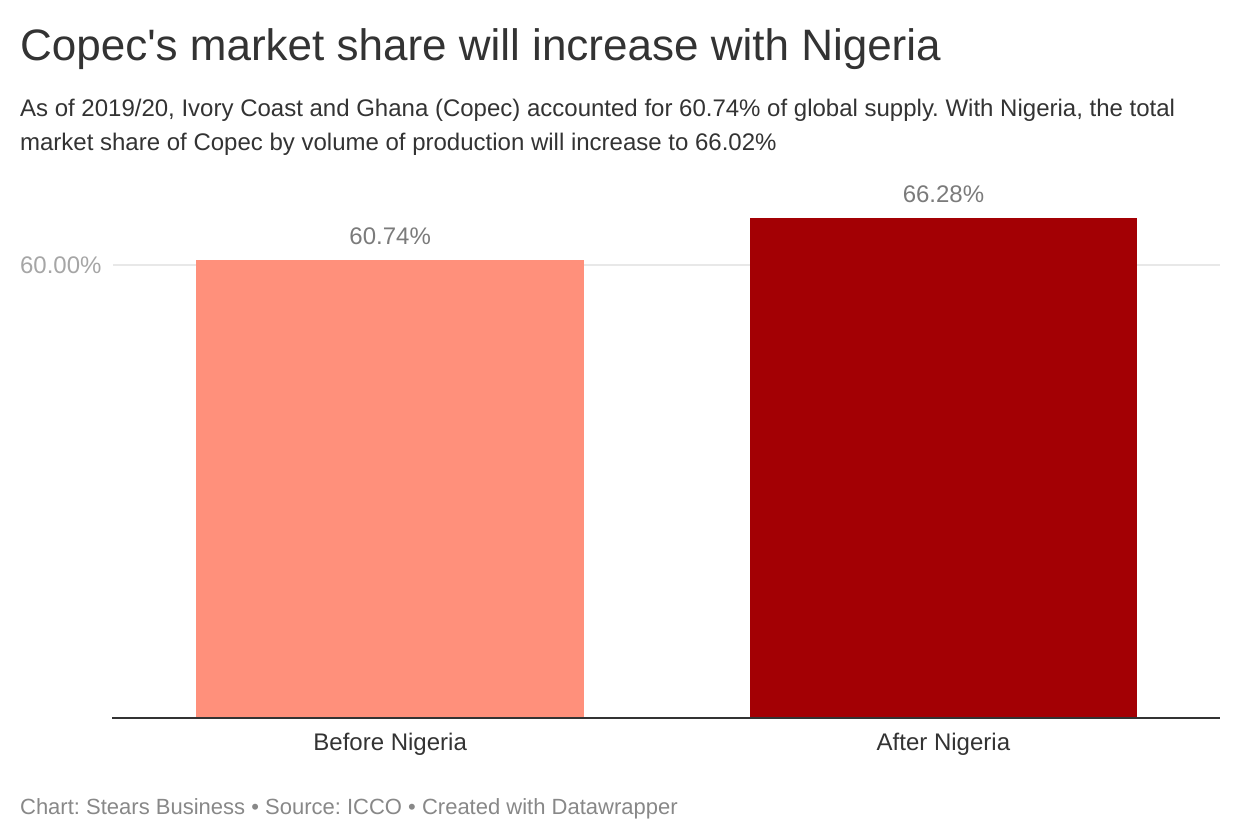

Recently, the Nigerian government announced plans to join COPEC—the cocoa cartel that supplies over 60% of the world's cocoa. But who exactly is COPEC, and what does joining the cartel mean for Nigeria?

Cocoa is an excellent place to start

Before unpacking the cocoa cartel and the implications of Nigeria joining the alliance, let's talk briefly about Nigeria's cocoa industry.

Cocoa—the raw ingredient responsible for the edible delight we call chocolate—used to be Nigeria's top export commodity in the 1950s and 1960s until crude oil. Nonetheless, cocoa is Nigeria's top traded agricultural export product and is the sixth most traded commodity contributing 1% to total exports in Q4 2021.

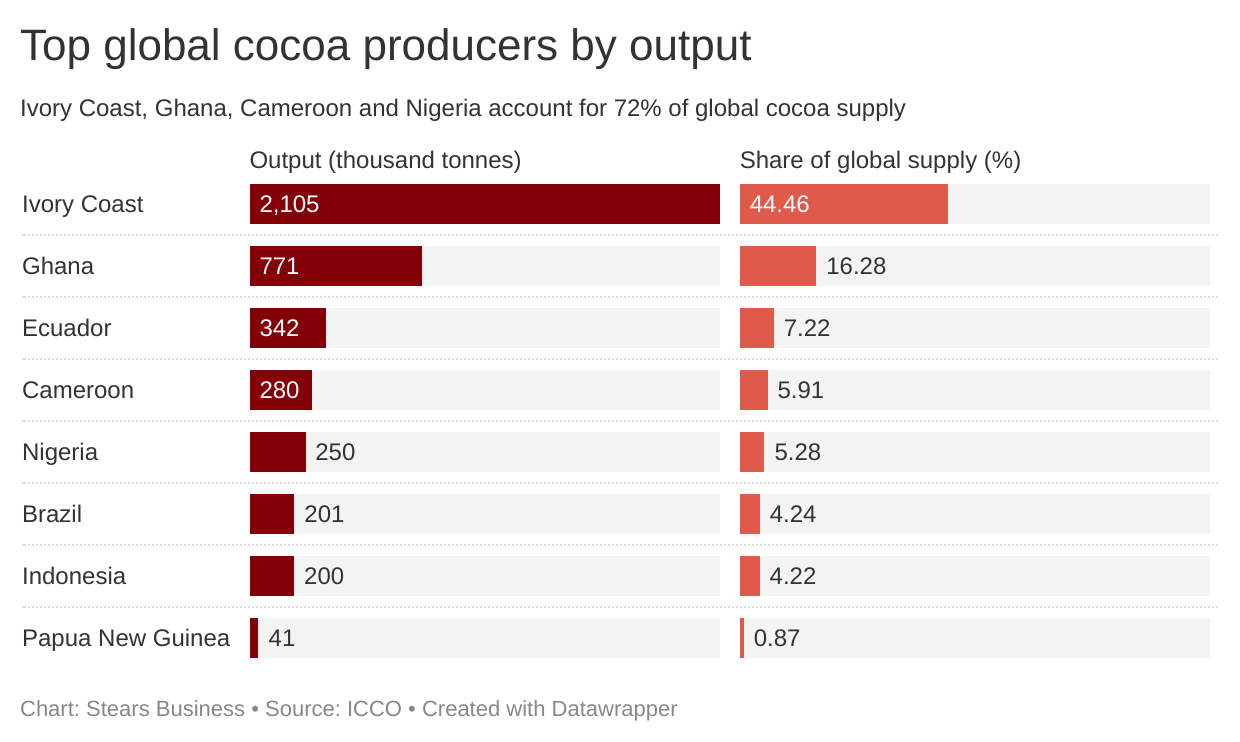

Nigeria is the 5th largest global cocoa producer, after Ivory Coast, Ghana, Ecuador and Cameroon, with an annual output of 250,000 tonnes produced predominantly in the country's southwestern region (Ondo, Oyo, Osun, Ogun and Ekiti). About 300,000 smallholder farmers active in the country's cocoa industry cultivate an estimated 800,000 hectares of land yearly to harvest and process the bean (ferment and or dry). In Q4'2021, cocoa beans (raw and fermented) fetched Nigeria a combined export revenue of ₦72.84 billion compared to other agricultural commodities like sesame seeds (₦40.72 billion) and cashew nuts (₦5.2 billion).

Despite the good news, there are issues.

As is typically the case with other commodities, the price of cocoa has been volatile over the years due to supply issues from the major exporting countries in Africa. In Nigeria, the cocoa industry's problems range from poor storage facilities to lack of fertilisers and pesticides, inadequate infrastructure, and, most significantly, farmers' poverty. Farmers in this industry have often beckoned on the government to increase infrastructure investments and provide fertilisers.

These measures should help farmers hedge against the volatility in global and domestic cocoa prices, mitigate the impact of adverse weather conditions beyond their control and reduce pests and diseases that negatively affect crop yields. Farmers require the kind of support that reduces the cost of cocoa production and improves their income levels. This year alone, the Cocoa Association of Nigeria stated that Nigeria could see its 2021/2022 main crop harvest (October 2021- September 2022) slump by 20%. The association noted that output could be around 250,000mt - 260,000mt from the estimated 320,000mt as late and heavy rains threaten the crop and raise the risk of pod disease. In terms of cocoa processing, the only by-product Nigeria extracts to a reasonable export quantity amongst the various options (powder, liquor, husk and butter) is cocoa butter. Cocoa butter is currently the eighth most traded agricultural export product in Nigeria, generating ₦652.43 million in Q4'2021.

So far, we have established a revenue problem facing Nigeria, which underscores the need to explore alternative sources of income for the government. With a focus on agric commodities, we have identified a former powerhouse, cocoa, that could do an excellent job of boosting the government's purse. And for the government to gradually milk the benefits of the commodity and address problems with its cocoa market, it intends to join the latest cartel in the commodities space, Copec. We only hope that the government does not overly depend on cocoa as with oil.

Now let's find out what the cocoa cartel is all about.

'Copec' - The almighty cocoa cartel

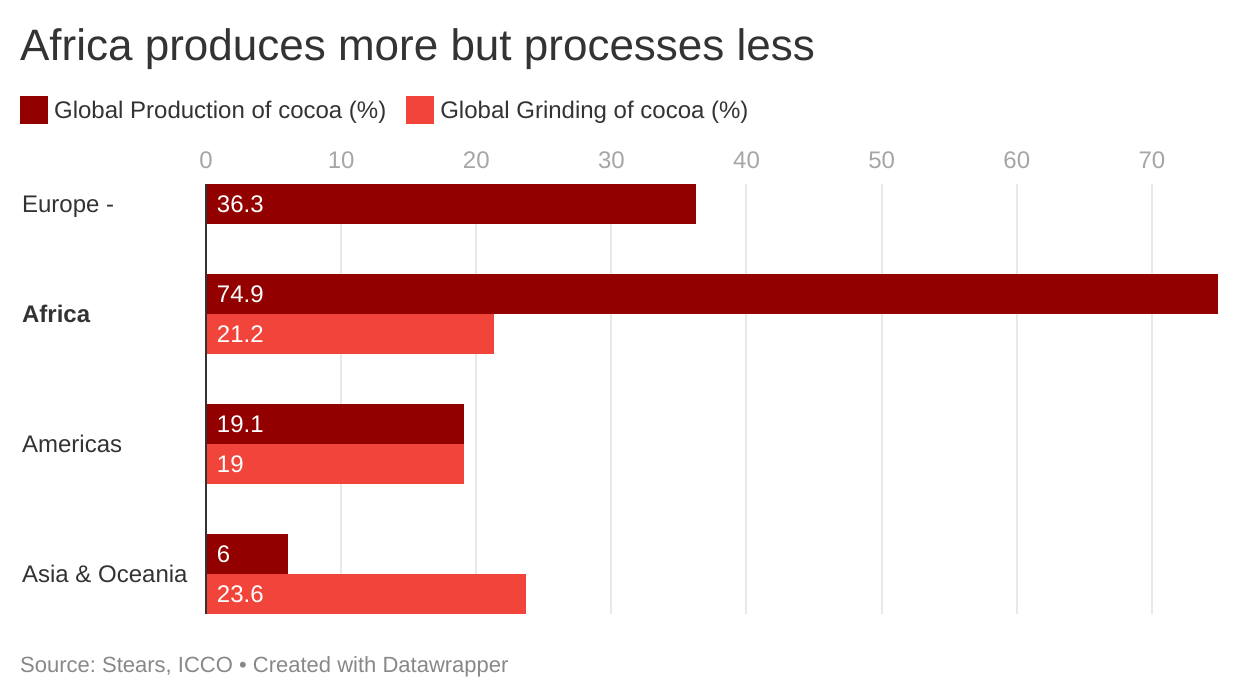

Copec was created in 2019 by the Ivory Coast and Ghana, the two West African nations that account for over 60% of the global cocoa supply. Taking a cue from the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the cartel running the oil market, the cocoa cartel operates an oligopolistic market structure (few sellers and many buyers). Their sole aim, like OPEC, is to manage cocoa output/supply, thereby controlling the global price, keeping it high enough to break even and improving the living standard of cocoa farmers in their respective countries. Eventually, they intend to enhance cocoa processing, add more value to the commodity and continue to increase export revenue. The cartel's processing and value addition goals are critical because, despite being the top global cocoa producer, the region barely accounts for 20% of the total global cocoa processing market, valued at $12.4 billion (2020).

To achieve its primary goal of alleviating farmers' poverty, COPEC, by leveraging on its collective market dominance, agreed to a minimum export price of $2,600/mt and a farmer price floor by attaching a Living Income Differential (LID) of $400 per tonne on every cocoa contract sold. This is the leading parallel between OPEC and Copec. A price floor is a government or group-imposed price limit, and it is the lowest possible price that can be charged for a good or service. For the price floor to be effective, it has to be higher than the market price, which, more often than not, is determined by the forces of demand and supply. With the global price of cocoa still bullish between $2,500mt and $2,700mt, the cartel's price floor of $2,600 plus the LID of $400/tonne is adequate to achieve its goal.

The LID, simply put, is an initiative centred around the farmers to boost their income. Farmers at the bottom of the cocoa production and processing stage essentially make less income, which trickles down to their standard of living. The issue of poverty amongst cocoa farmers has been often attributed to unequal distribution of profit margins, increasingly becoming a widespread issue that raised concerns around the sustainability of the supply chain.

From 2019 to 2020, Africa supplied 75% of the world's cocoa, but farmers received only 3% to 6% of the final consumers' price for refined products like chocolate. West African farmers are also exposed to climate issues that expose their crops to pests and pod disease. This often reduces their output levels and waters down their bargaining power for a better selling price. Basically, the farmers take on a lot of risks and are not adequately compensated for it. Further, most cocoa farmers generate about 66% of their total household income from just cocoa. So, when sales are meagre, their entire household feels the pinch. According to a report by the KIT Royal Tropical Insitute, even if you multiply the net income generated from cocoa by 3, it would not be sufficient to close the living income gap for cocoa farmers fully. This is why Copec wants to solve the problem.

With Nigeria planning to join the cartel, the market share and dominance of COPEC will increase, thereby raising their price-setting capacity and ability to increase income for farmers. Meanwhile, the benefits accrued to Nigeria from the alliance range from improved revenue to wealthier farmers (an incentive to more farmers coming on board), increased investor appetite for the domestic cocoa industry, job creation, and enhanced economic growth and development.

Farmers are the gold mine

We have been able to identify that Nigeria, despite the challenges facing cocoa production and processing, could be on the road to greatness by joining the cocoa cartel.

We have also established that the LID structure is set to alleviate farmers' poverty.

When we look at who could benefit from this arrangement, the three main stakeholders are the farmers, companies, and the Nigerian government. Let's look at how these different players interact: Farmers are responsible for carrying out the primary activities needed to produce cocoa. The cocoa beans are harvested and processed (dried and or fermented) to extract the liquor, pulp and initial by-products, which the farmers then sell to companies like Nestle and Cadbury. These companies use cocoa to produce chocolate, cocoa powder and beverages. The government is also a buyer in this process, intending to export to generate revenue. There are some other chain links, but this is as basic as the interaction between the stakeholders goes.

To reiterate, farmers are the gold in this arrangement.

Why?

Improving the livelihood of cocoa farmers can go a long way in encouraging more people to find employment in this industry. Aside from that being Buhari's dream, Nigeria is currently facing its worst unemployment crisis in decades so this could be a meaningful opportunity for those looking for work but cannot find any. Of course, as any labour market economist worth their salt will tell you, this depends on the pool of labour available. That is, we will want to ensure the available labour supply matches the skills required in the cocoa industry so we don't end up in a situation where people are underemployed (employed in work that does not use their full skillset).

There is also the fact that the agriculture sector is well-known for being our least productive sector (many people are employed here but few outputs are produced). If Nigeria is to join the cocoa cartel, meaningful investment must be made to also boost the production of farmers here to tackle this problem. Currently, the Cocoa Farmers Association of Nigeria (CFAN) ambitious plan to increase the country's cocoa output by 40% to 500,000mt in 2024. To achieve this, we need to see investment in cocoa processing infrastructure and a spread in the value chain.

In addition, for companies mainly in the fast-moving consumer goods industry, it means lower importation costs. For example, Nestle and Cadbury have had to import cocoa beans, despite Nigeria being a global producer, because local supply is falling short of their production needs to satisfy the domestic demand for their products. Reducing their import spending will encourage expansion and backward integration (a situation that allows companies to take control and or support suppliers and improve supply chain efficiency).

It is about acting fast

Ultimately, the news around Nigeria possibly joining a cocoa cartel is a welcome one. However, our experience with OPEC has shown that even belonging to an international cartel does not always spell good news for our local industry. On the one hand, Nigeria has struggled to meet oil production quotas, which has stopped us from benefitting even when oil prices are high. And on the other hand, commodities like cocoa and oil tend to make countries fall prey to the resource curse if they become overly dependent. These are two caveats the Nigerian government must watch out for if it is to switch its focus to the cocoa industry.

Regardless, the benefits abound—from reducing the risks that farmers (who are the most vulnerable in the value chain) to incentivising increased productivity in a sector that could boost export earnings. For Nigeria to realise all that has been mentioned in this piece, it goes beyond deciding to join—it entirely depends on actually joining the cartel and taking the necessary steps to improve the cocoa industry.