27th June 2022.

A day we have been anticipating for five years. The day history will be made when Nigeria repays the principal of its $300 million diaspora bond.

Forgive the hyperbole; Nigeria’s first diaspora bond was once considered quite a big deal. For a little while, news reports were filled with stories of Nigeria’s first-ever diaspora bond. Shortly after the launch, one of my articles on the topic was even featured on Brookings alongside Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Akinwumi Adesina, and President Paul Kagame.

Five years on, I may be the only one that still cares about Nigeria’s diaspora bond.

Key takeaways:

-

Nigeria’s first-ever diaspora bond will be repaid in June 2022 when the Federal government settles the $300 million debt. Even as Nigeria has binged on Eurobonds in the past few years, we have shown little interest in issuing another diaspora bond.

- Diaspora bonds sit somewhere between charity and investment,

From pioneer to anecdote

A lot has changed in five years. Over that period, Nigeria’s fiscal authorities experimented with three new debt instruments in a bid to diversify its debt portfolio: Sukuk, the federal savings bond (FSB), and the diaspora bond.

Of these three, only the diaspora bond was never repeated.

The Federal Government (FG) issued its first Sukuk in 2017, raising ₦100 billion from Shariah-compliant investors. Since then, it has issued two more Sukuk totalling ₦260 billion. If you have gone past Eko Atlantic, Lagos any time in the last eighteen months, you would have seen a prominent billboard indicating that the road (Ahmadu Bello way) was funded with a Sukuk.

Meanwhile, the federal savings bond (FSB) was introduced around the same time as a way of improving Nigeria’s retail savings rate. In the 2017-2020 Economic Recovery & Growth Plan, gross national savings were estimated at 11.3% of GDP, with the government setting a 2020 target of 21% of GDP. The FSB was considered an important tool to help achieve this.

At the time, many economists were puzzled by the FSB. Although it was packaged as a bond and a long-term investment alternative to treasury bills, FSBs were missing many of the features of a regular bond and had more in common with a standard fixed deposit you would get at a commercial bank. Compounding matters, interest rates on these savings bonds were much lower than inflation and similar-tenored debt. This remains true today as the Debt Management Office is currently selling two-year savings bonds at 7.3% and three-year savings bonds at 8.3% in a country where inflation has averaged over 10% for years. All of this made me think that FSBs would die a silent death, but they have kept going and Nigerians keep buying.

So, both the Sukuk and savings bond have had follow-ups. And both were launched for the first time in 2017. Just like the diaspora bond. Yet the Federal Government seems to have abandoned the diaspora bond experiment (for now, at least) even though we have raised about $15 billion in Eurobonds since then.

That $300 million diaspora bond that was much-vaunted back in 2017 is a drop in Nigeria’s external debt ocean. That's 1.9% of Nigeria’s total outstanding Eurobonds (roughly $16 billion), and 0.8% of all of Nigeria’s external debt (about $40 billion). The diaspora bond is so insignificant that when we repay the principal on the 27th of June, it would only be slightly higher than the interest payments made on external debt in the last quarter of 2021 ($286 million).

All of this is to say that five years later, Nigeria’s diaspora bond is an anecdote that few will remember.

The diaspora vault

Despite all this, Nigeria’s diaspora bond is actually very important for the simple reason that the diaspora matters. And I don’t just mean this in socio-political terms. Nigeria’s diaspora matters a lot for its development.

Setting aside the unimpeachable reality that Nigeria needs as much financing support as it can get to escape its present economic rut, the diaspora is a particularly attractive demographic of potential financiers. More specifically, diaspora bonds still hold an allure—there is a reason why the 2017 issue was accompanied by so much fanfare.

Here is the simple economic logic of diaspora bonds.

As an issuing country, you benefit from a patriotic discount where you can sell your bonds below market rates. They also strengthen the relationship between a country and its diaspora, which should be a good thing for economic development.

Crucially, we have seen this work in practice, most famously in Israel, where diaspora bonds were first issued 70 years ago. More than $30 billion has been raised since then, making Israel the undisputed standard for diaspora bonds. Other countries have used them more sporadically and still found success. For example, India tapped its diaspora multiple times when it faced balance of payment crises in the 90s—who better to help stabilize the country’s exchange rate than its economic army of citizens abroad?

The benefits to the diaspora are also pretty clear. You get a chance to invest in Nigeria’s development from the comfort of your Shanghai or Paris home and you become less reliant on friends and family back home that sometimes divert your remittances to other uses.

Alas, none of these would matter without the fact that the Nigerian diaspora is a potential cash cow (in the nicest possible way).

In 2009, Sub-Saharan Africa’s diaspora savings were estimated at more than 3% of the region’s GDP. Since then, more than $250 billion has flown into Nigeria in remittances alone. Back in 2009, Nigeria had the largest remittances per emigrant—just under $12,000 came into the country for each emigrant. Apart from Lebanon in 2nd place, the next country was China with about $6,000 per emigrant. A lot has changed since then, but it is unlikely that Nigeria has fallen far down this table.

These numbers will only rise in tandem with Nigeria’s recent Japa wave, especially when you consider the millennial and tech-oriented dominant demographic riding this wave.

Nigeria urgently needs funds to avoid a prolonged fiscal crisis. The diaspora has money. Nigeria, meet diaspora.

The diaspora is loyal

The most amazing thing about diaspora inflows or remittances is their stability over time. Given that Nigeria’s unstable foreign exchange (FX) environment is a primary cause of many of our present economic woes and a crippling constraint on investment and policy, finding a stable source of sizable dollar inflows is like locating candy mountain.

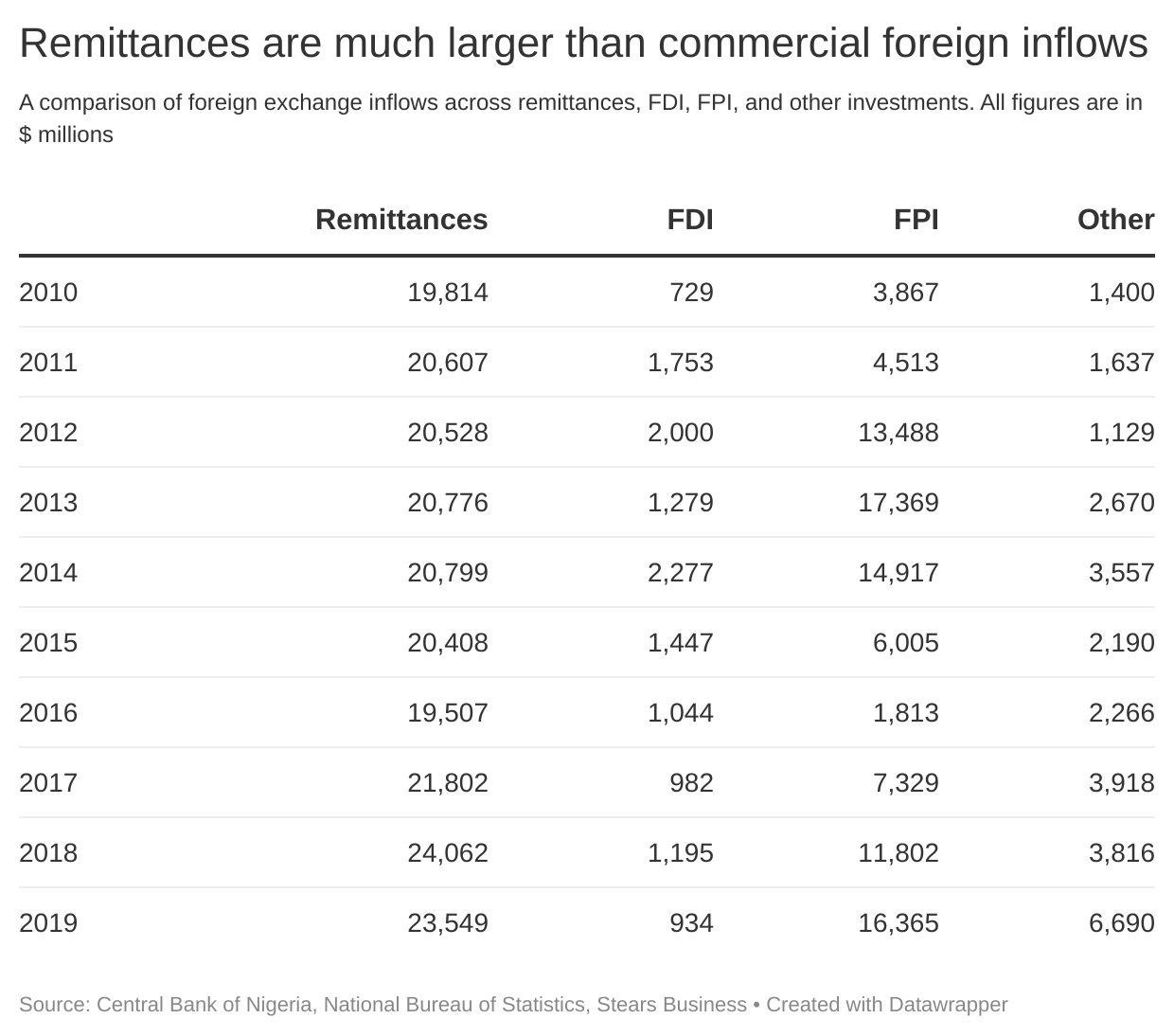

We can see this clearly by comparing remittance inflows to foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign portfolio investments (FPI), and what the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) refers to as “Other investments”, which is basically made up of FX loans to the government (e.g., Eurobonds) and other miscellaneous inflows.

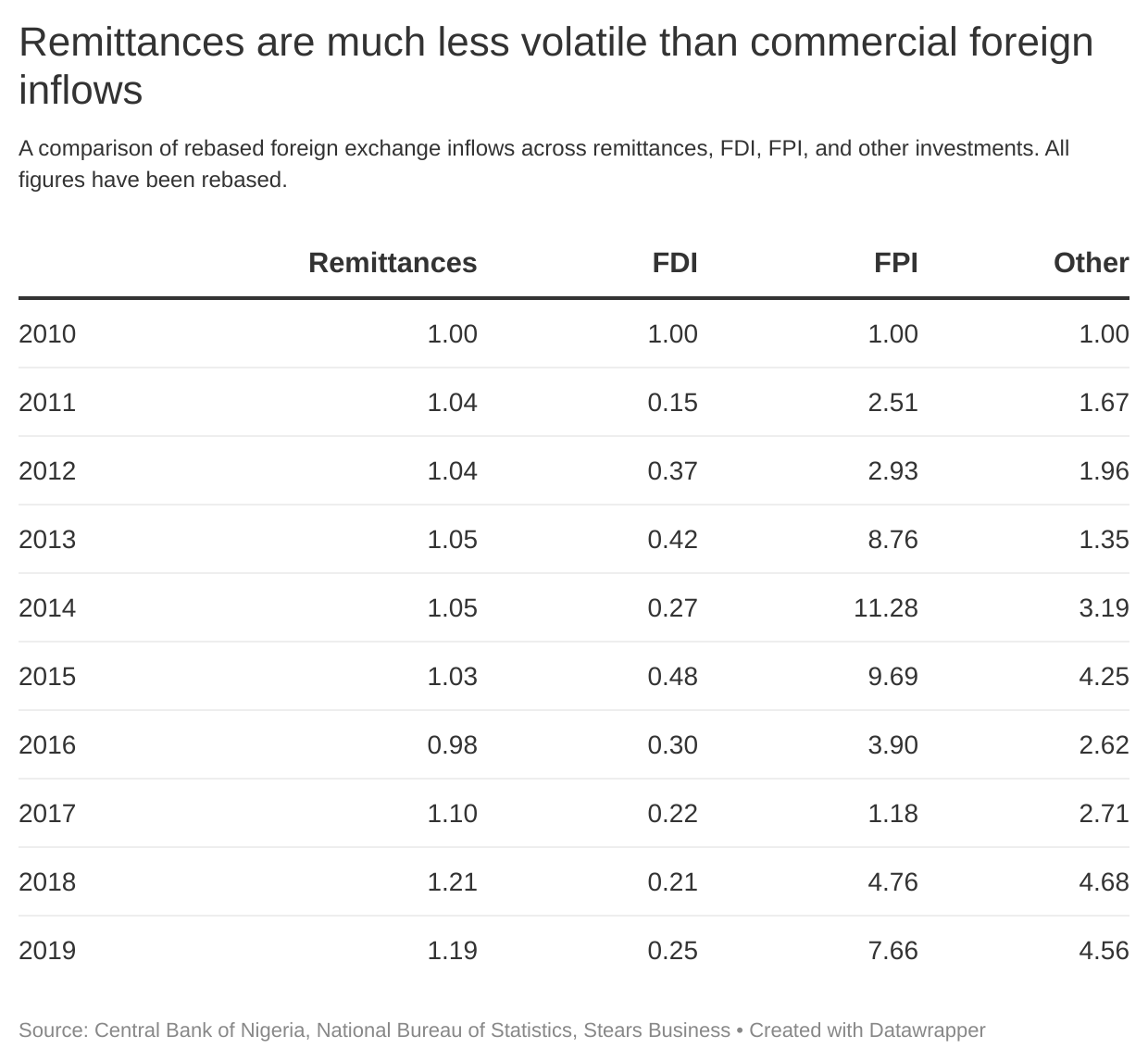

We cannot directly compare the volatility of all these inflows because they have different magnitudes; for example, remittances were twice as large as FPI in 2019 and almost 20 times greater than FDI. To get a true comparison of their volatility, we must “rebase” them. In layman’s terms, we take each indicator’s values and divide them by its starting value (e.g. for remittances, we divide the 2010 value by 2010, 2011 value by 2010, and so on).

The effect of this is that all the indicators now have starting values of 1 (because we divide their 2010 values by their 2010 values) and values for subsequent years are *multiples* of the starting year. You can see what this looks like in the two tables below.

The first table shows the original amounts, and the second table shows the rebased amounts. Taking FPI as an example, the rebased table tells us that 2013 FPI was almost nine times greater than 2010 FPI, while 2019 FPI was almost eight times greater than 2010 FPI.

Now that we have the rebased amounts, we can directly compare these inflows to see which is the most volatile. We can actually do this mathematically by calculating the variance of each of the inflows over the period. The variance is a commonly used measure of how widely spread numbers are, so more volatile inflows should have higher variances, and less volatile inflows should have lower variances.

Here are the variances for each indicator:

- Remittances: 0.005

- FDI: 0.054

- FPI: 12.362

- Other investments: 1.628

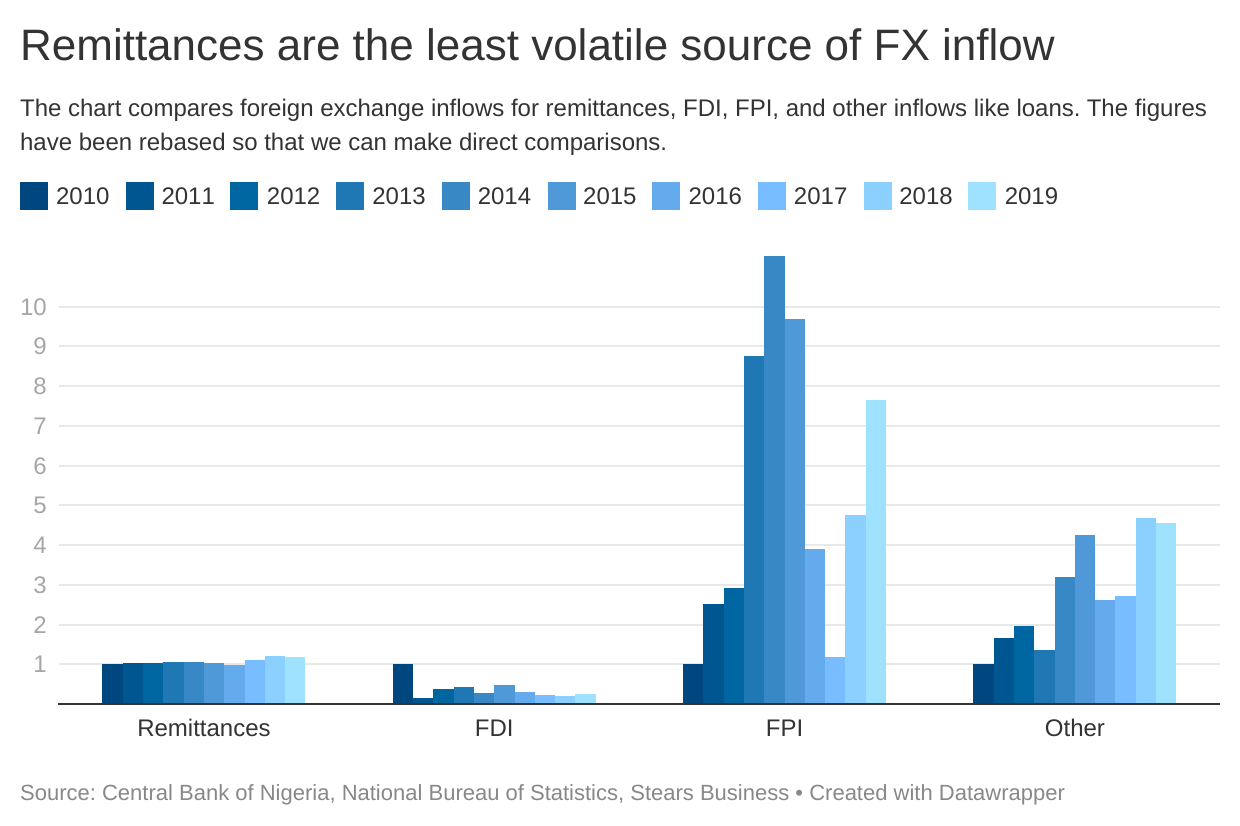

No surprise that remittances have by far the lowest variance—proof that they are the least volatile inflow. You can also see this visually in the chart below (the chart also uses the rebased numbers). Notice how the remittance bars are the most stable over time.

The slight caveat here is that remittances used to be very stable until they dipped in 2020. This was partly a global trend triggered by the coronavirus pandemic. But in Nigeria’s case, the 2020 dip happened because Nigerians living abroad were increasingly using informal or semi-formal remittance channels like peer-to-peer cryptocurrency transfers. So, although remittances tracked by the Central Bank of Nigeria fell between 2019 and 2020, actual remittances likely remained resilient, so the underlying point about remittances being stable remains true.

Do you really want my money?

If diaspora bonds are so great, why has Nigeria not issued any since 2017?

Well, it’s not for a lack of investor appetite. Consider that Nigeria’s 2017 diaspora bond issue was more than 30% oversubscribed, while countries like Ghana, Kenya, and Ethiopia failed to meet their issuance targets.

By all accounts, Nigeria’s maiden diaspora bond has been a success, so why haven’t we seen a follow-up?

One easy explanation is that for Nigeria, Eurobonds are a much easier sell and could easily crowd out diaspora bonds (which would be lower-yielding). This is a country that could raise $1.25 billion in Eurobonds a few days after the Minister of Finance publicly said it would be a bad idea to do so, and when its debt service bill for 2021 swallowed basically all the government’s revenues.

In the last five years, Nigeria has raised roughly $15 billion in Eurobonds. At this point, it comes easy.

In contrast, diaspora bonds are trickier because they come with more strings attached. Apart from the fact that they are harder to sell because only the diaspora can purchase them, they also lock the country into a social contract with the diaspora (at least that’s the idea) that has political and social implications. When you look at countries that have issued multiple diaspora bonds (e.g., India and Israel), they have strong diaspora ties, which also means that the diaspora has a greater say in how economic activities are organised in the issuing country.

When the ministry of finance can tap commercial investors for $1.25 billion impromptu, with no questions asked, you can see why they would be less keen on the diaspora bonds and the socio-political baggage they bring.

This baggage partly explains why few countries have experimented with diaspora bonds despite their purported benefits—and diaspora remittances rising each year.

According to the World Bank, global diaspora receipts were just over $125 billion in 2000. These receipts grew steadily before peaking at $705 billion in 2019. By 2019, there were at least 16 countries that received more than $10 billion in diaspora inflows (including Nigeria). More impressively, there were 28 countries where diaspora receipts were more than 10% of GDP (Nigeria not included). There is clearly potential for galvanising diaspora flows, yet outside Israel and India, few countries have made much progress. Ethiopia famously paved the way in Africa with its 2008 Millennium Corporate Bond issued to fund Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation projects. However, the sale underwhelmed amid scepticism over the viability of the projects and heightened political risk at the time.

How do we turn things around?

The good news is that if Nigeria ever decides to revisit diaspora bonds, we will not have to figure it out on our own as enough clever and curious people have tried to crack the nut of how to galvanise diaspora investments sustainably.

Making Finance Work for Africa (MFW4A), DMA Global, and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) designed a toolkit to help governments figure out a good diaspora investment strategy, from identifying opportunities to boost diaspora investments to designing investment instruments like diaspora bonds.

Some of the recommendations included in the toolkit are ideas I have previously hinted at. For example, one of the highlights of the toolkit is that “countries need to leverage the clear non-financial link to their home country that many migrants have” but are novel lessons too. Like the claim that although the consensus is that many diaspora investment efforts have been unsuccessful, there is less agreement about what success looks like outside trying to emulate Israel.

Likewise, the toolkit suggests that diaspora investments are more likely to succeed if the investment areas or projects are not just selected by the government (as is usually the case) but emerge from consultations with other groups like DFIs and the diaspora itself.

Ultimately, the toolkit reinforces the point that getting diaspora investments right is hard work, even if it pays off in the long term. Commenting on the issue, the Chief Executive of DMA Global stressed that “developing a diaspora investment programme is a thorough process that requires long-term commitment, involves considerable time in planning and product design, and significant resources in execution to reach and mobilise the diaspora”. As I advised back in 2017 before Nigeria issued its diaspora bond, “The diaspora should not merely be seen as a source of funds but as genuine stakeholders in the development of the economy and society.”

The truth is that regardless of what policymakers do here, remittances will keep flowing into Nigeria. Even more so now that digital innovators are dismantling barriers and driving down the costs of cross-border transfers in Africa. At the end of last year, Chipper Cash, a cross-border payments startup, was valued at $2 billion, barely four years after its founding date. And older fintechs like MPesa and MFS Africa continue to grow, with the latter securing an additional $70 million equity investment in a Series C in 2021. Encouragingly, the market is maturing, evidenced by the rise in bespoke diaspora investment solutions like Bongalow, a startup that facilitates diaspora mortgage investments in Nigeria and Ghana.

As we saw earlier in the article, the remittance market is huge. Nigeria alone receives $20 billion or so each year—and these are only recorded inflows. If policymakers dither over leveraging these funds, you can be sure that Nigerian entrepreneurs will not.