One thing you might notice from our articles at Stears is that we are bullish about the technology ecosystem in Nigeria (tech ecosystem). But this is just not blind excitement, the data backs this up. In this article, we showed how the Telecommunications and Information Services sector (the best proxy for the ecosystem in Nigeria) is growing faster than the overall economy, attracting new investments and creating high-paying jobs for Nigerians.

This excitement has also led us to look at other important issues, such as startup valuations and the question of who is building Nigeria’s startups. The article on the identity of those building Nigeria’s startups has some interesting insights that point to the existence of inequality in the ecosystem. The tech ecosystem with its potential to provide significant financial returns to founders and investors can widen existing inequality.

Key takeaways:

- The Matthew effect refers to the tendency for initial advantages to

This article explores this further by focusing on a potential source of inequality—the Matthew effect. If you are curious about what the Matthew effect is and how it affects the tech ecosystem, you should read on.

As told by Matthew

In 1968, Robert K Merton, a renowned sociologist released a seminal study where he identified a phenomenon in scientific research, where famous scientists received recognition for their discoveries over and above lesser-known scientists that had the same discovery; Essentially, famous authors outshine lesser-known authors, reinforcing the initial fame and pushing the other authors into relative obscurity.

He titled this phenomenon “the Matthew effect,” drawing the name from the book of Matthew in the bible (13:12, 25:29), which goes something like this—'those who have will be given more, and those who have less will see that taken from them'. In other words, the “rich” get richer and the “poor” poorer. The Matthew effect notes that initial advantage tends to lead to more advantage and at the same time initial disadvantage results in a further disadvantage with the end result of a widened gap between those who started out with the advantage and those who were initially disadvantaged.

To help us get a good grasp of this, I borrow an analogy from Dr Daniel Rigney, author of the book that explores this concept in-depth. A game of monopoly.

For those not familiar, monopoly is an economics-themed board game, where players trade a fixed stock of properties with different values and compete to accumulate assets while driving other players into bankruptcy (basically becoming a monopoly). All players start out with the same amount of “money” and an equal shot at buying properties, accumulating assets, extracting rental income and winning the game. Luck and skill ultimately play a role in this.

Now imagine a modified version of this game, where players start with different amounts of money. Say player A starts with $8,000, player B $2,000, player C $500 etc. In this variation of the game, which more resembles real life, the player with $8,000 has an upper hand and can at the start of the game monopolise the best assets and properties; and since the assets are fixed, other players will be forced to acquire lower value properties and have to keep paying rent until they become bankrupt.

Even though the players with lower starting amounts can possibly usurp the game and end up winning through skill and luck, the odds are stacked against them invariably. This is what is called absolute Matthew effect, where an individual builds on their initial advantage to move ahead of “disadvantaged” others who fall behind with the gap between the “have more” and “have less” widening.

Let us look at a more relatable example. Imagine a secure investment opportunity with a guaranteed annual return of 10% and the offer to compound presented to two individuals—Tolu and Oge. Tolu has ₦10,000 to invest, while Oge has ₦100,000, the initial gap is ₦90,000 only. After year 1, Tolu will have a total sum of ₦11,000 while Oge will have ₦110,000, they have both grown their investments by 10% but the gap between them is now ₦99,000. After 10 years, Tolu will have ₦25,937.42, while Oge’s account will show ₦259,374.25. The difference between their investments now stands at over ₦230,000. Even though both of them have increased their investments, Oge has gotten richer with no extra effort.

You can see how the Matthew effect can play out to widen initial differences in advantages. And as I have shown the tech ecosystem through startups and the investments in them can deliver outsized returns. So we need to look at whether these current and future benefits are accruing to those with some type of advantage

Is there a Matthew effect in the tech ecosystem?

To answer this question, we will rely on data and see what it says. But before we hone in on Nigeria, it is important to explore whether this can be observed in other markets or regions.

This report on the state of fintech in emerging markets by Catalyst Fund and Briter Bridges is a good place to find information on this. The report surveyed 177 startups and 33 investors across emerging markets to understand investment trends, product categories and general performance of fintech. The report states that it has a bias towards the sub-Saharan Africa region.

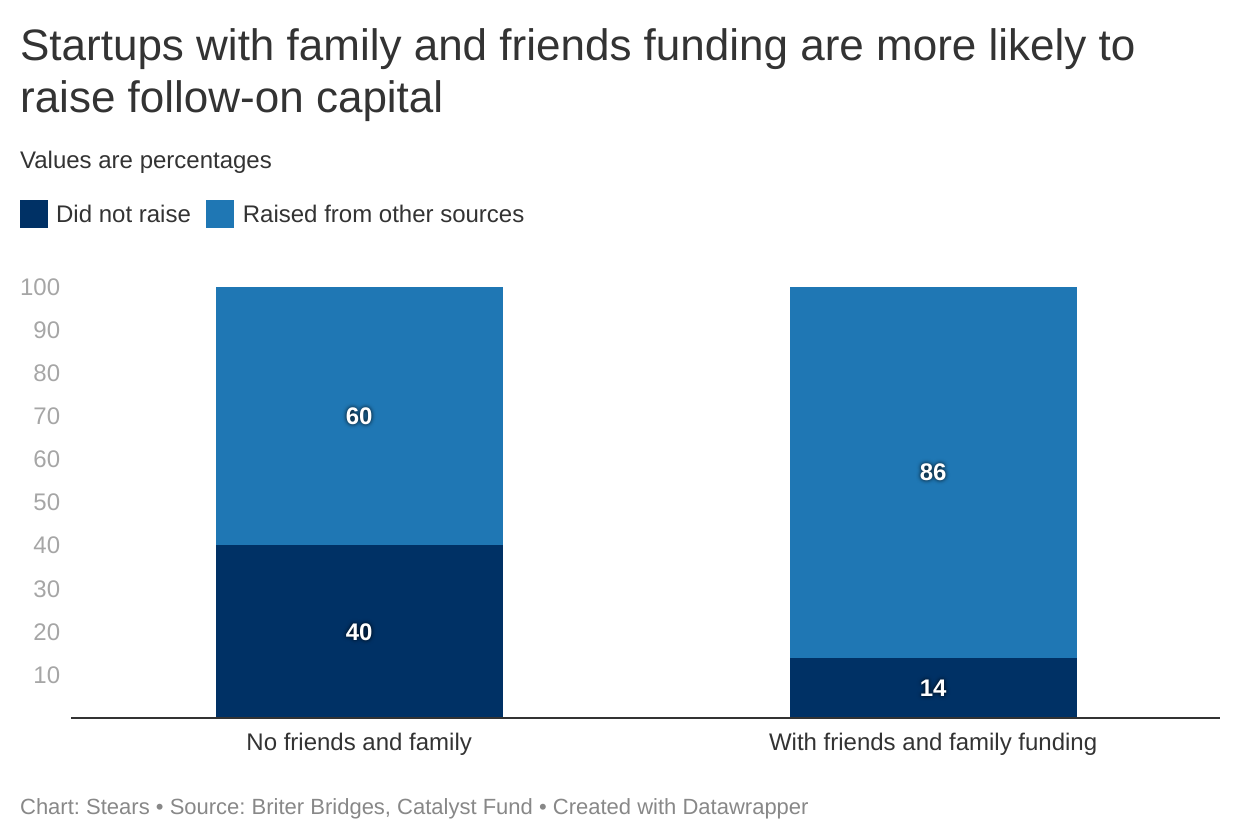

Based on the analysis of responses on startup funding, the report found that the ability to raise from Family and Friends (F&F) and the amount raised was a predictor of whether the company will be able to raise in subsequent rounds and the size of the amount raised. 64% of startups surveyed were able to raise an F&F round and 86% of these companies went on to raise subsequent funding as opposed to 60% of startups unable to raise an F&F round.

An F&F round can range from $10,000 to $150,000. We can agree that having friends that can part with this amount, when a startup most likely does not have a product or traction is in itself an advantage.

And as this shows, this advantage compounds upon itself in a typical Matthew effect fashion, by influencing the amount that the startup can go on to raise according to the report. As capital is important to running a startup and growing it, startups with larger investments have a higher chance to succeed, all things being equal. Indeed, the report in interpreting its findings stated that “founders with limited access to capital-rich communities early in their startup journeys may later face greater fund-raising challenges overall.”

Even though this survey is skewed to SSA, with Nigerian companies featuring significantly, it still does not give us evidence beyond a reasonable doubt to answer our question. So we need to dive deeper.

We turn to the Africa: The Big Deal database on funding rounds in the African ecosystem. We will be relying on data from here between January 2019 and March 2022 for the analysis. Since funding is critical to the ability of individuals to establish and grow their startups, this can help shed light on our question.

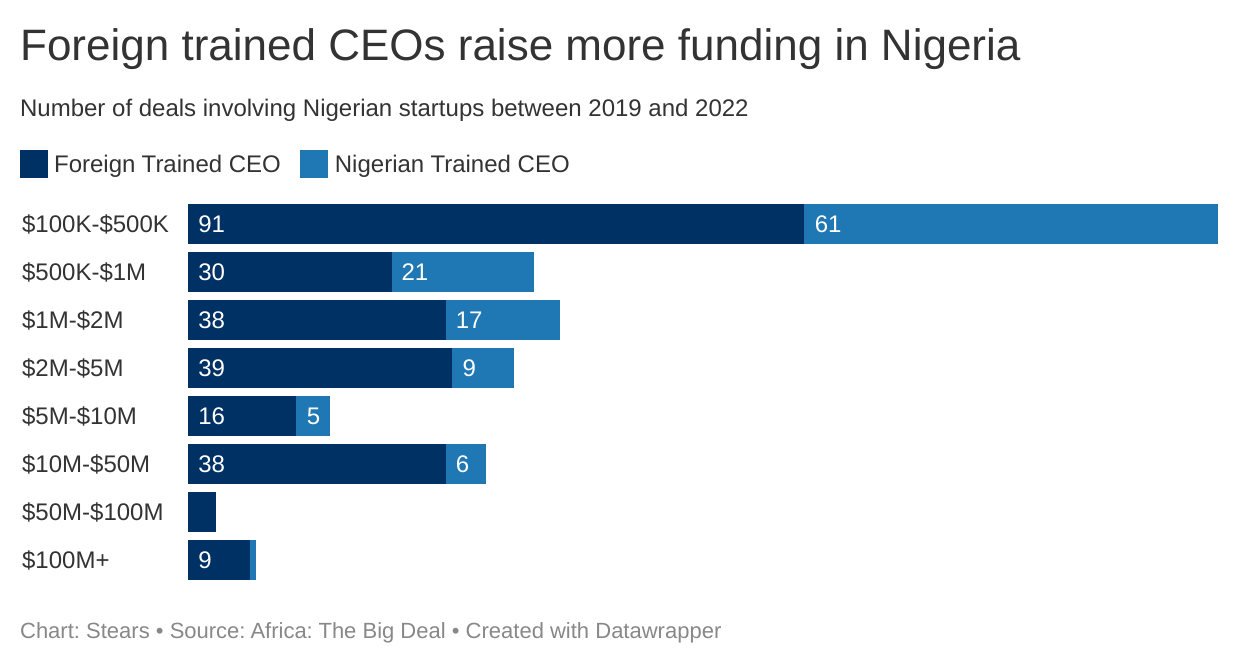

According to information captured by the database, Nigerian headquartered companies account for 390 deals. Of these deals, 389 have the education information of the CEO. Looking through the database, what we find is that startups with foreign-trained CEOs account for approximately 69% of all funding rounds between 2019 and 2022. This in itself should not raise any eyebrows. We can expect founders who are educated outside Africa in countries like the US, where there is a strong startup and risk-taking culture to establish or lead startups in Nigeria.

But looking at the data further throws up some more insights.

In the $100,000 - $500,000 funding range, startups with foreign-educated CEOs were involved in 60% of the funding rounds. And even though this drops by a percentage point when we get to the $500,000 - $1 million range, startups with foreign-educated CEOs dominate subsequent rounds with only foreign-educated CEOs raising in the $50 million - $100 million range.

Essentially, foreign-educated CEOs are able to participate in more fundraising rounds and raise more than Nigerian-trained CEOs, with the effect that they are likely set up for success. Here we see a pattern that mirrors the findings from the Catalyst fund report, except this time the advantage is a foreign education.

Is this the Matthew effect? let us explore this further. For starters, foreign-educated CEOs may be non-Nigerians educated abroad, Nigerian migrants (or their children) or Nigerians who go abroad for education. Any way you slice it, what we come up with is that a foreign education costs money. For instance, in the US, tuition for undergraduate and postgraduate programmes can cost somewhere between $20,000 to $45,000 per year and in the UK, £12,000 – £20,000 (US $16,690 – $27,820).

Not all students who go to school have to pay their way but consider this, in 2020 only 7% (or 1 in 8) students received a scholarship for college education in the US.

So it turns out that being able to afford a foreign education translates into an advantage that founders can leverage to raise more funding and push their startups ahead. At the same time, while it may seem like foreign-educated founders only have an initial economic advantage, there is more. Foreign-educated CEOs would also have relationships by being in alumni networks, and this may be crucial to open doors when they intend to raise funding. As this article from Harvard Business Review notes, relationships are key to fundraising for startups.

Interestingly, this trend mirrors the Africa-wide trend as observed in this analysis. Also, there have been similar findings in a country like the US, where 50% of top ten schools that produced the most startup founders are Ivy league and elite colleges.

If it’s not broken, don't fix it

At this point, someone might point out that it is not just the tech ecosystem that is affected by the Mattew effect, seeing as we can observe it across Africa and even in the US. In other words, maybe this is just the natue of the ecosystem and we do not need to interfere with it. This would be a fair argument, but we need to remind ourdelves of why the Matthew effect is important.

At its core, what it does is to widen the gap between people within a field or society, leading to more inequality. This is even worse when there is existing inequality in a society, such as is Nigeria with a gini coefficent of 35.1. This becomes more important when we consider a feature of the tech ecosystem, it has a potential for significant rewards to the founder; imagine a liquidity event like an acquisition where a founder can become a billionaire, as was the case with WhatsApp. Look at another point, the technology sector is the industry that has the second-highest number of billionaires globally.

High levels of income inequality hurts everyone in a society. An analysis by the OECD finds that reducing income inequality boosts economic growth. Additionally there have been studies, such as this one, which finds a relationship between inequality and prevalence of health and social problems such as violence, low interpersonal trust, mental health issues, drug abuse. When you consider that Nigeria has its own fair share of violent crimes and social issues, this becomes all the more relevant.

Another indirect effect of rising inequality is a reduction in people with effective demand. This medium article from partner at DFS lab shows that in Nigeria only 3.7 million people are able to spend over $10 per day. A reduction in this population will likely shrink the Total Addressable Market for consumer facing startups.

Finally, a system that favours those with initial advantages prevents us from backing and benefitting from some brilliant and impactful ideas from those who are not able to break in.

And history gives us a tale of caution. In the 50s the discovery of crude oil must have been believed to improve incomes for Nigerians, at least Chief Sunday Inengite and his kinsmen must have felt so on the day oil was discovered in Nigeria. But despite this, the number of people living in extreme poverty increased from 36% in 1970 to 39% in 2021 according to the World poverty clock. If this looks like a small jump consider that the 1970 figure translated to 20 million people, but in 2022 we have over 83 million people, a four fold jump in 50 years. And research has found that inequality is a key contributor to poverty in Nigeria.

Know which other sector is now being referred to as “the new oil”?

What can the ecosystem do?

So far we have been analysing funding and the ability of founders to raise based on their educational backgounds. What the data shows is that there is an observed Matthew effect.

But there is one thing to bear in mind; especially from the side of where the funds are coming from. Investors have a huge and difficult task—identifying startups (ideas and teams) with potential to justify and return the investment. This is even more so for foreign investors, with insufficient context and understanding Nigeria’s market. They then likely rely on signals like education or intros within the network as a key factor in making an investment decision.

What this translates to, is limited opportunities for those without those signals. So solving this will entail increasing the opportunities available to these people.

One way to do this is by empowering local Nigerian investors with more capital. Investors that are able to identify underrepresented Nigerian-trained founders both male and female with ideas that can scale. While in this case it may be those without economic and social capital, it can also be backing more women founders, such as firstcheck is doing.

Another way is by increasing the number of local competitions and programs that identify entrepreneurs and give them access to funding based on the viability of the idea. One example that easily comes to mind is the Tony Elumelu Entrepreneurship Programme (TEEP) that takes entrepreneurs through a selection programme and gives them a $5,000 seed grant based on their performance in the programme.

Finally, we can make the ecosystem more inclusive by funding ideas and startups that create opportunities for other founders; this can be through crowdfunding or crowdraising platforms like GetEquity. These make it easy for startups to raise from retail and institutional investors and increase the overall funding channels or opportunities.

Ultimately mitigating the Matthew effect requires us to first accept that this is happening, it then requires us to prioritise it as we have seen that it will continue in its path without any deliberate and conscious intervention.