Last week, I went through the onboarding process for six African fintech apps.

Why? I needed to send money from Nigeria to Uganda, and I learned a thing or two.

First, I'm not an early adopter. Try as I might, the uncertainty surrounding whether a new application or software will meet a job to be done is nerve-racking and simply uncomfortable. Second, sending money to Uganda is not as easy as I expected. With a growing number of applications offering cross-border transfers in Africa, I expected something as easy as a 1, 2 step.

Key takeaways:

-

The whole market does not adopt innovations at the same time. Instead, we embrace them over a period, and different adopter categories do so at varying times, based on their willingness and ability to try new ideas.

- Nigeria is still in the early adoption phase for digital payments, with 22% of respondents surveyed by

Admittedly, I may have complicated the process by conducting my due diligence on each application. For this, I needed at least one recommendation from my network and the ability to directly contact an employee at the company to help resolve any issues that came up—and no, the regular customer success email or number did not suffice.

Finally, if you want to send money to Uganda, Eversend is not a bad option. You might hit a few bugs in the process, but Olaoluwa got me over the line, and I thank him for that.

What does this rant have to do with the market for fintechs in Africa?

It prompted the question: where is market adoption for fintech products, and how much more could the market grow? If spending power in Africa is small but growing, how much adoption is required to justify the price tag for the companies? How long will it take to get there?

After encountering the friction in cross-border transfers, I considered if previous experiences with new applications differed. They weren't. For instance, I logged onto Kyshi ten or more times before I caved and used the platform to convert British Pounds to Nigerian Naira. Now, I occasionally use the app if I can't find someone in my close network to exchange with. Over the last few months, I created accounts on Chipper Cash, Lemonade Finance, Abeg and Brass. Yet, I'm unsure if or when I will eventually use the applications.

But this is just one user's perspective, and we have to concede that it takes time to build apps such as Revolut or TranserWise.

I often create these accounts to stay on top of new trends and tools, but I do not become an adopter until later in the cycle. My personal best for late adoption is Twitter. After creating an account in September 2009 on my 15th birthday, I only became an adopter over a decade later—after the launch of Stears.

This is not unusual and tracks with the Diffusion of Innovation theory.

A successful innovation that reaches significant market adoption goes through stages of adoption by different adopter groups.

The whole market does not adopt innovations at the same time. Instead, we embrace them over a period, and different adopter categories do so at varying times, based on their willingness and ability to try new ideas.

Adoption is facilitated through interpersonal network interactions. Thus, assuming an initial adopter discusses the innovation with two or more people in their network, and they become adopters who pass the innovation along to two or more peers, and so on, the resulting distribution follows a binomial expansion (as in the chart above).

Identifying where users stand in the adoption cycle is key to determining who your change agents will be. These are the power users and evangelists that will sing praises in their networks to improve the adoption of an innovative product.

Non-consumption meets innovation

Where the market is in the innovation diffusion curve has implications for how we value innovative products.

Although it is impossible to reach full market adoption, the stage of innovation (and the resulting products) on the diffusion curve is influenced by factors other than whether it satisfies a job to be done. These factors could include the product's cost, inconvenience and complexity, and a host of other factors.

In low-income countries, these factors are characterised by traits of non-consumption.

Non-consumption is the inability of a person or company to purchase and use a product or service required to fulfil an important objective, e.g. sending money to Uganda. It is important to highlight that non-consumption isn't just a result of low incomes (affordability), though it contributes significantly. The inability to get the right product or service to fulfil a need can result from a lack of accessibility and availability to the consumer.

Take, for instance, attempting to make an online transfer without access to mobile internet or a smartphone. Context-specific innovations like USSD codes provide a solution in this case, but there are many other barriers to conducting seemingly simple financial transactions.

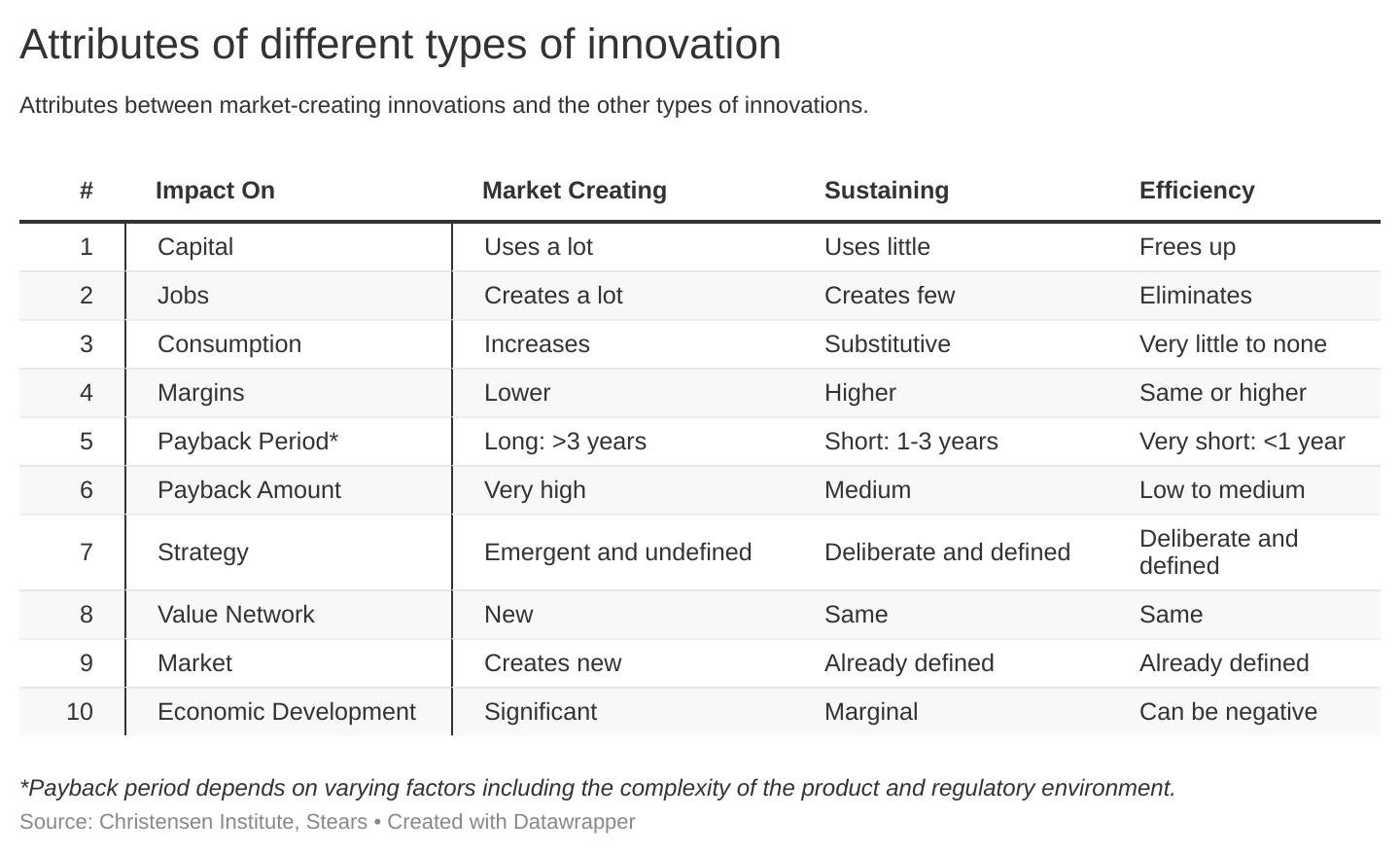

Innovations that target non-consumption expand the market for a particular product by bringing new users into the market. These are known as market-creating innovations, as defined in The Innovator's Dilemma by Clayton Christensen. Some key characteristics of market-creating innovations include its margins, which are lower than other types of innovation, and the payback period, which tends to be longer.

Mobile money is another example of a product that targets non-consumption. Millions of lower-income consumers who needed to access banking services—save, transfer funds, etc.—had to make long and expensive trips to the bank, which inevitably meant a smaller proportion of them used banking services. However, access to mobile money services brought those non-consumers into the market for banking services.

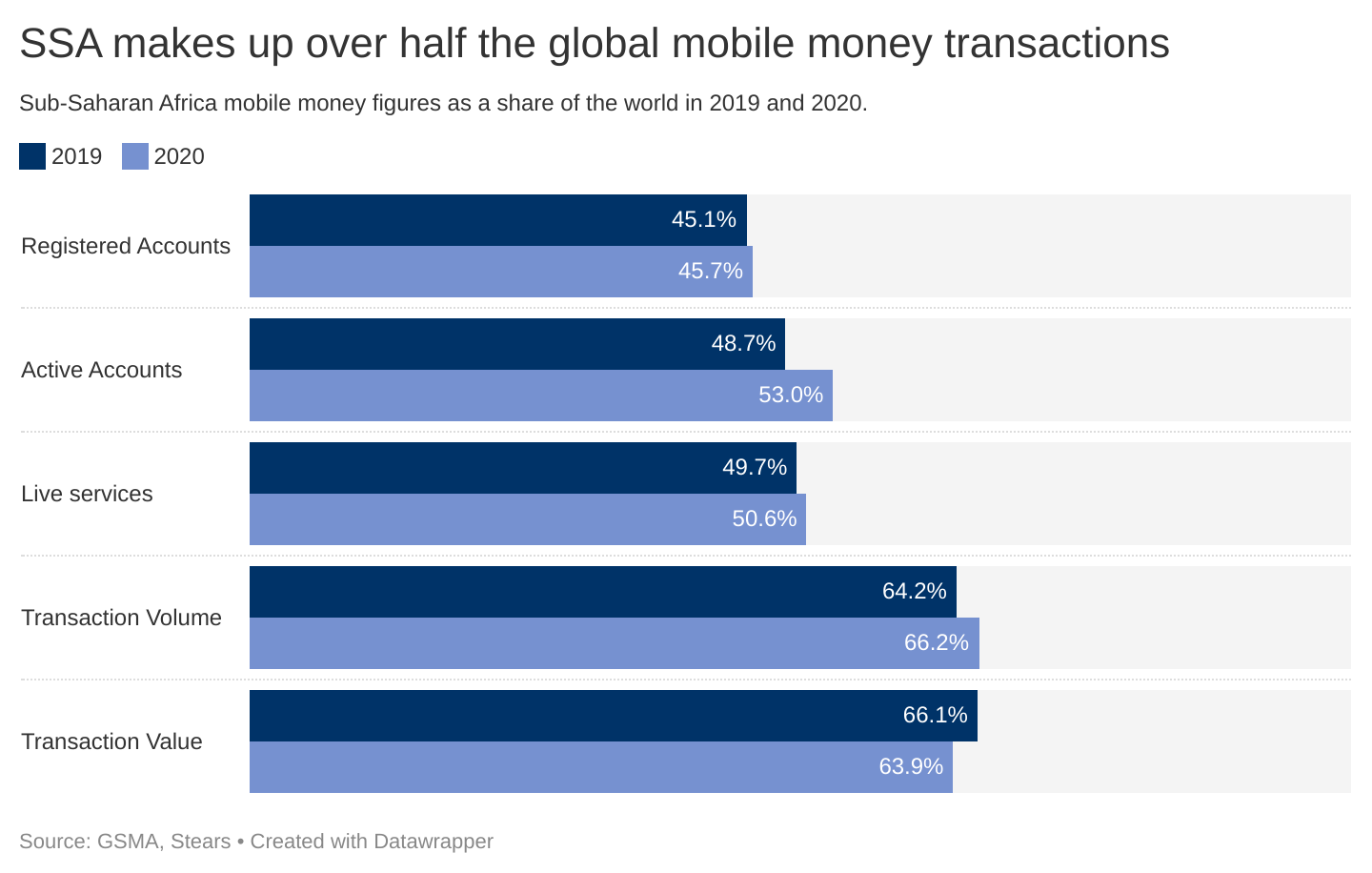

Today, Sub-Saharan Africa makes up around 66% of transaction volumes and 64% of transaction value conducted using mobile money.

Targeting non-consumption is tricky as the absence of a market is a lot more difficult to notice than the presence of a large market. It's also counter-intuitive: to target non-consumers, you do not necessarily go to a large market; you go where there is no obvious market. You look for places where consumers are using workarounds to tackle fundamental problems.

Before the world of mobile banking products, consumers relied on creative methods to transfer money. Some used envelopes and physically sent them to people in other cities via taxi drivers. At the same time, some acted as informal money agents making transactions on behalf of people who didn't have access to banking services. These are less common today, but it is clear that where solutions are hacked together to tackle common problems, that's usually a sign of non-consumption.

M-Pesa, the mobile money service success story that began in Kenya in 2007, capitalised on this opportunity. But today, it is not expanding into Nigeria. Instead, its most recent expansion plans include Ethiopia and, surprisingly, Romania, which raises the question of what a European version would look like and whether there are barriers to entry that make Nigeria unappealing.

Have Nigerian digital payments moved past early adoption?

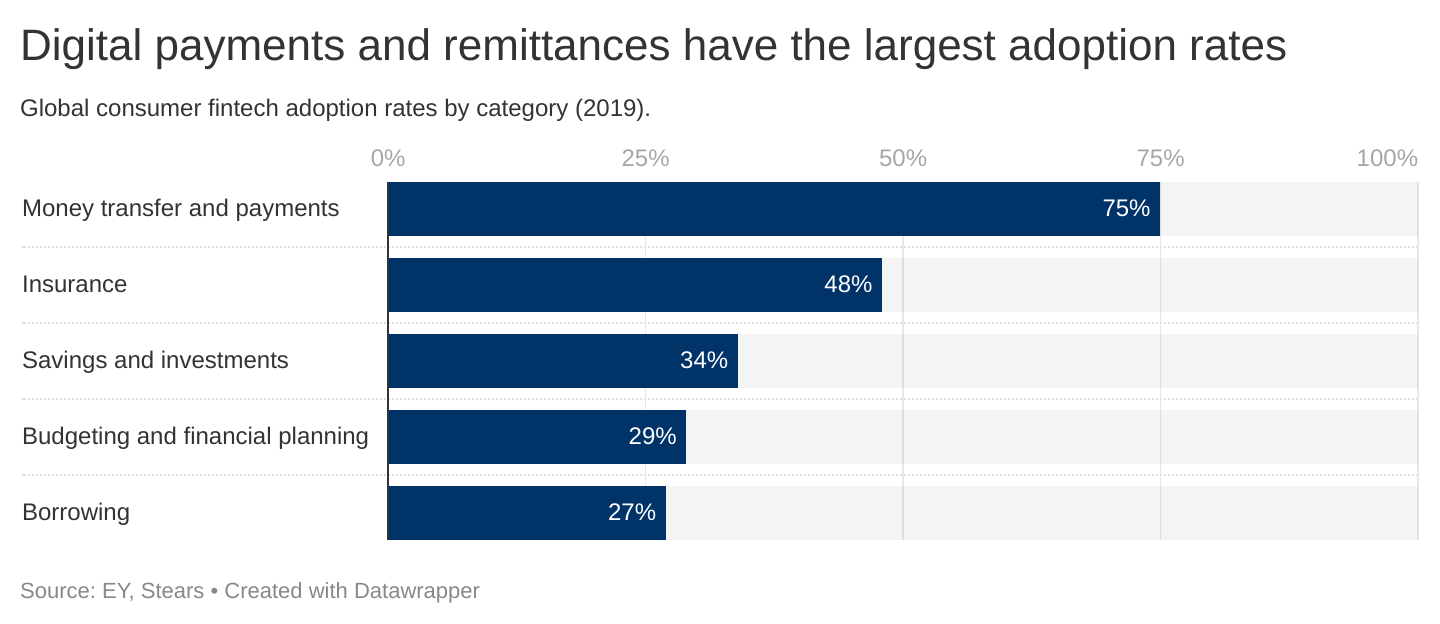

As a sub-category of the fintech sector, digital payments (including remittances) have seen the quickest adoption globally and in Africa.

But not all countries have seen similar progress.

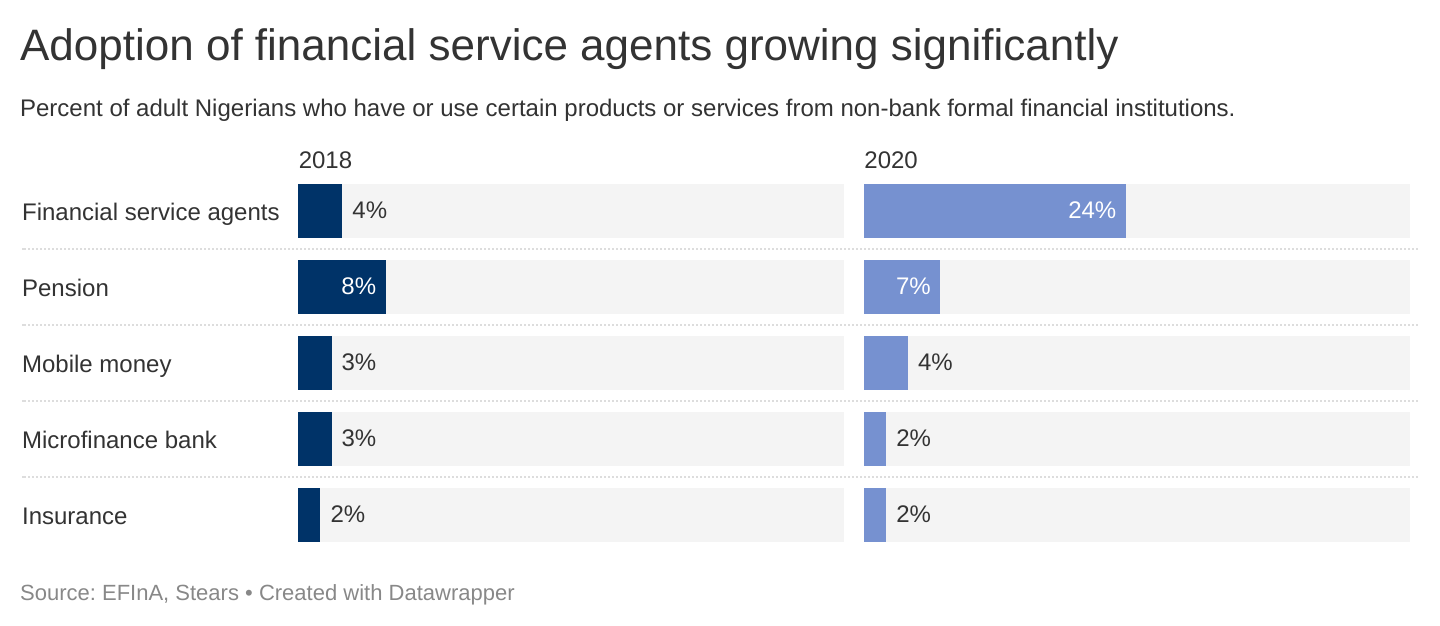

Nigeria is still in the early adoption phase for digital payments, with 22% of respondents surveyed by the Enhancing Financial Innovation & Access (EFInA) programme reporting they were aware of mobile money and 4% stating they had used it.

Less than 30% of adult Nigerians still had or used products or services from non-bank formal financial institutions.

A significant issue still faced by companies offering financial services products to customers in Nigeria is awareness and the ability to reach customers where they are. As these are often customers with even lower spending power, it is challenging to get them cost-effectively.

Payments systems realise significant benefits of scale when network effects kick in and average cost drops—both for individual providers and at the market level. According to McKinsey's estimates, above scale, mobile money can be a 35% margin business; but small providers need to spend over two times what they earn to maintain their size. Providers can break even once there's sufficient value flowing through their systems, estimated at around $2-3 billion in annual transaction value and revenue of roughly $20 million to $30 million.

It is not a surprise that companies like Flutterwave in their early days focused on enterprise clients, where one customer could be equivalent to 10,000 small to medium-size businesses in total payment volume. And with adoption still at an early stage, it is difficult to imagine how many payment companies can make their margins work. Getting to a $3 billion in annual transactions is no easy feat, and less so in a single country. Since its inception, Flutterwave has processed just over 200 million transactions across Africa valued at over $16 billion, which averages just under $3 billion in annual transactions.

Not every company will hit Flutterwave's reported numbers, so it is fair to assume that progress may be slower for the rest of the market.

Gradually, then suddenly

To gain the benefits of scale, payment providers must invest heavily and with long time horizons. This holds worldwide for internet players in network businesses—firms such as Alibaba and Google have invested significantly in long-term growth and market capture, even when this means immediate losses. Since a rosy end-state business model means little without the ability to make the initial investment, successful providers have to draw on their reserves, find long-term investors, or look to partner with larger international organisations.

Without a doubt, international plays will be required. We've already seen partnerships between the likes of Paystack with Apple Pay. Mobile network operators (MNOs) may also look to group-level mobile money strategies and resource sharing for their country-level businesses to succeed. Individual providers or partnerships that already have the capabilities needed to grow will have an easier time attracting investment than those that need to build competencies.

This means there's work to be done and it has a knock-on effect on the expected payback period for investing in the market.

However, suppose the payback period could be longer for the African market. In this scenario, operators will have to justify the high value placed on fintech companies as they can't always wait for the complete adoption cycle to run its course. Given the pressure of venture investment, it makes sense to keep expanding into new markets even if innovators and early adopters form a small proportion of the market. By starting the process sooner, entrepreneurs and investors spread their bets across markets.

But expectations still need to be tempered. It is more realistic to anticipate extended payback periods in African markets. The uncertainty operators are frequently challenged with, whether from regulation or infrastructure—the list is extensive—should provide reservations to entrepreneurs and investors alike on time required to overcome these challenges.

Technological change often happens gradually, then suddenly. Small changes accumulate, and suddenly the world is a different place.

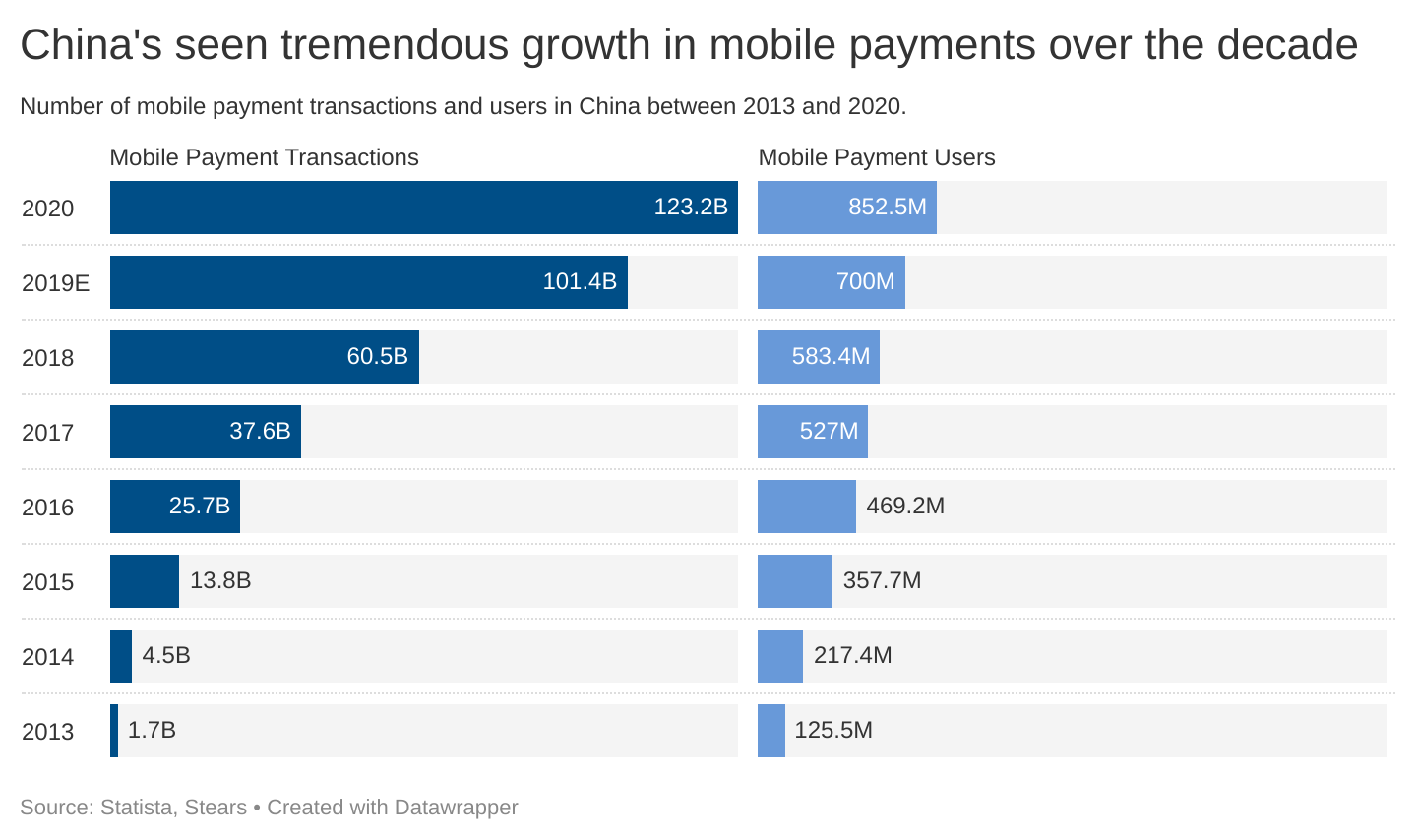

We've seen a similar trend in other markets, and it is likely to be the same in the African market. China provides an excellent example here, as back in 2009, there were just around 70 million mobile transactions conducted by a population of 1.3 billion. Contrast this with 2020, where the population now stands at 1.4 billion and mobile transactions are over 123 billion.

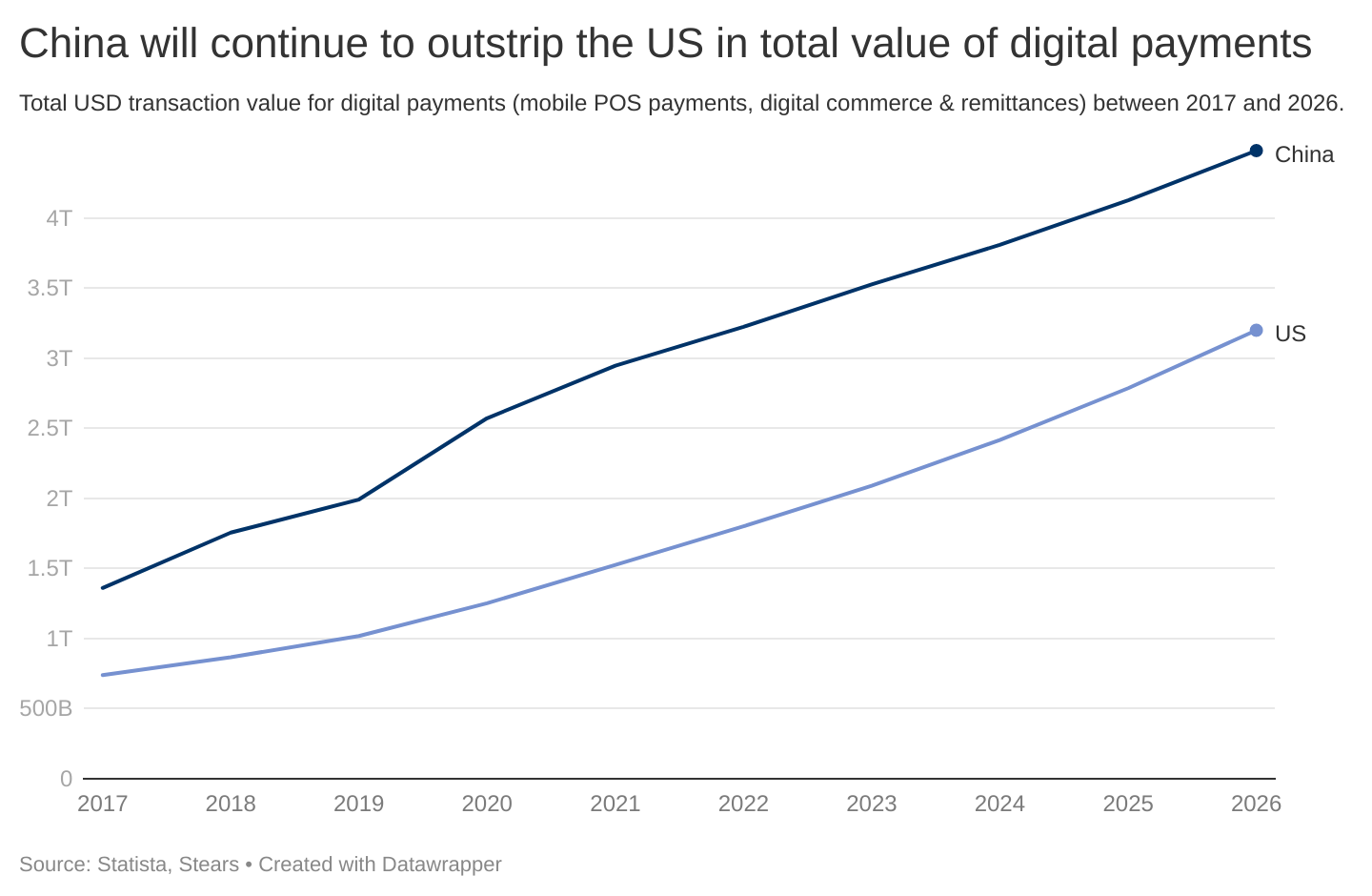

By 2026, the value of digital payments in China is expected to reach $4.5 trillion versus $3.2 trillion in the US. Considering just under a decade ago, China was processing transactions that were a fraction of its current volumes, it shows that exponential growth compounds over a longer period. The value of Africa's digital payments today stands at $98.5 billion (Nigeria makes up roughly $11 billion). Compared to the US and China, this may seem like a drop in the bucket, but digital payments are growing faster in Africa.

We can also expect to see new entrants in the market. It was recently announced that MTN and Airtel, two of the leading African MNOs in Nigeria, have been awarded licenses to operate Payment Service Banks (PSBs). The reach of these two MNOs in Nigeria should lead to the quicker adoption of mobile money as a payment method and a reduction in cash usage. This "payment method switching" trend will continue to grow in Nigeria and other African countries.

As for whether the market is big enough for African fintechs? The frank answer is not today, but tomorrow might be guaranteed.