If you've been living under a rock—or off Twitter—the last few weeks, you might have missed the Twitter-Musk saga, which appears to be ending in the billionaire successfully taking Twitter private.

On April 4, Twitter broke when Tesla CEO, Elon Musk, became its largest shareholder. The story spread with commentators giving their take on how his involvement may change the company's trajectory for better or worse. As the Twitter-Musk saga is nearing its conclusion, we look back on the company's performance, the challenges it is trying to overcome and how it intends to capture the creator economy. But we particularly dig deeper into why it matters to Africa's creator economy.

Key takeaways:

-

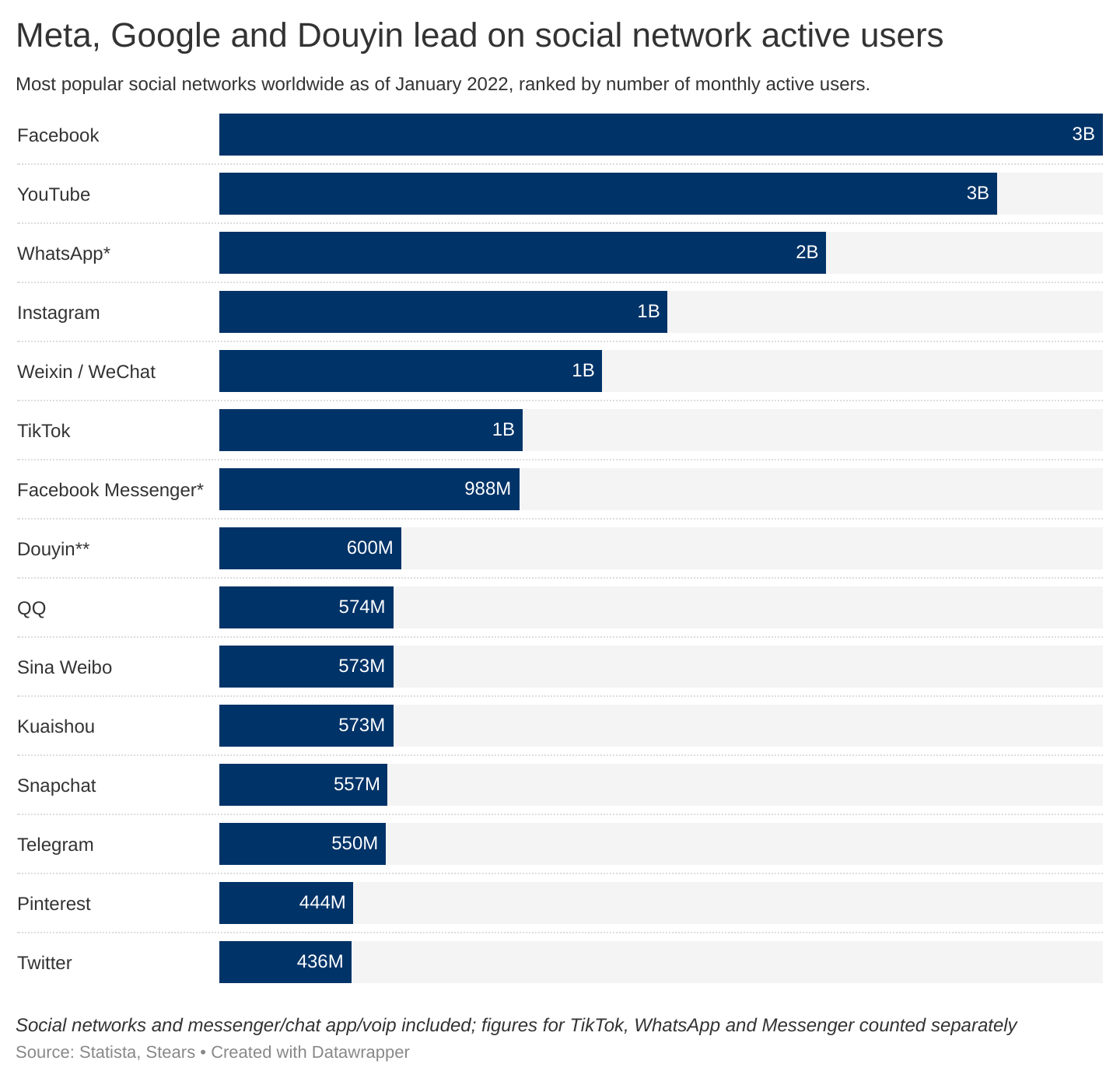

The world’s wealthiest man, Elon Musk, is on the verge of acquiring Twitter, the 15th largest social media site by the number of active monthly users.

- Twitter has struggled to keep pace with its Meta rivals and Google

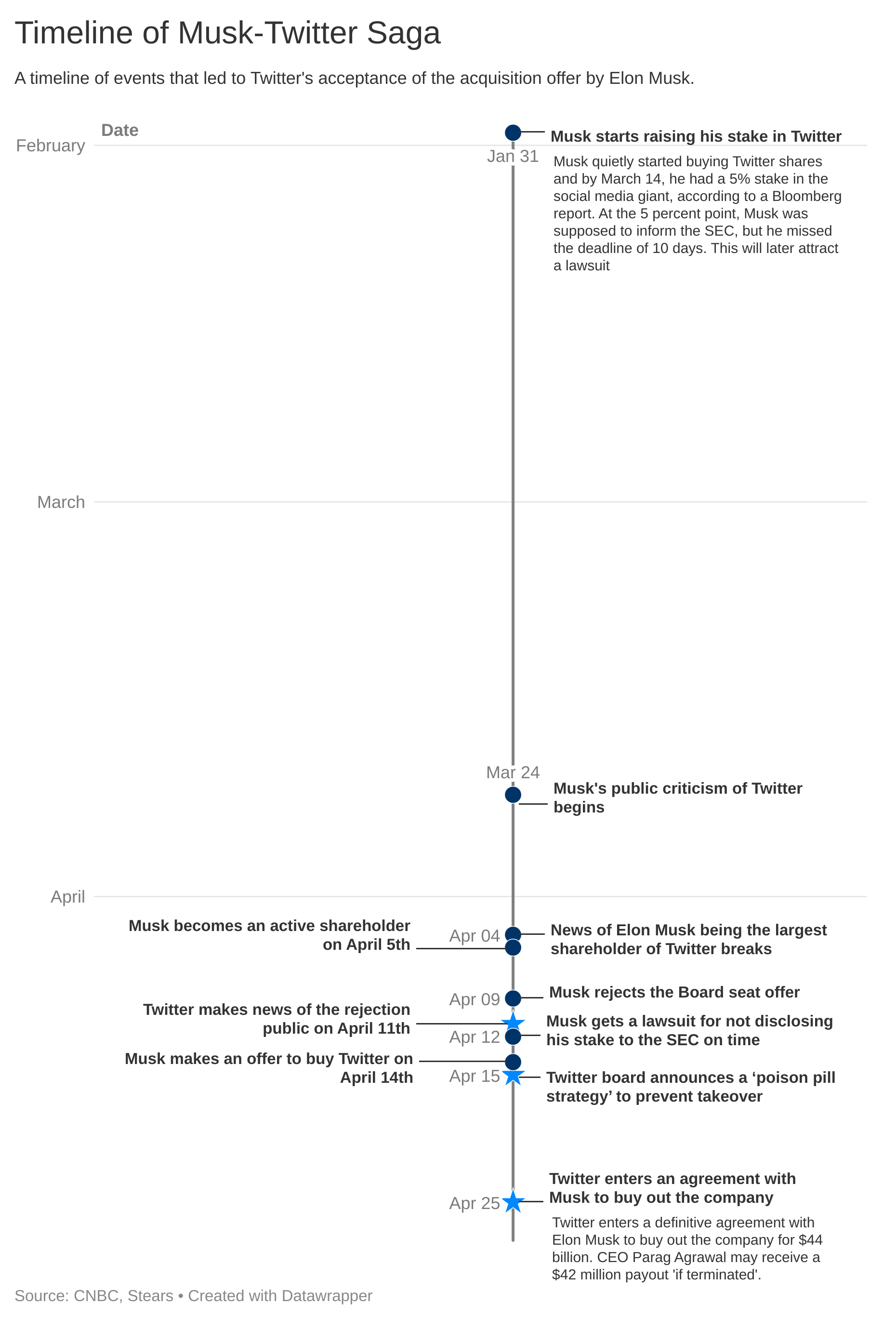

Here is a brief timeline for those who are trying to catch up.

Who said corporate drama could not be fun?

Musk’s tweetstorm has so far given little concrete information on the strategy for the company going forward but he’s indicated two areas of interest. The first is Twitter’s role as a public space for debate, which in turn needs to be protected, and the second is product improvements to help improve “trust” and user experience. This could also include plans to promote a subscription model so it relies less on advertising.

For now, we focus on Twitter’s performance to date and the opportunity it has to tap into the African creator economy by connecting it with a global audience through direct monetisation models like subscriptions.

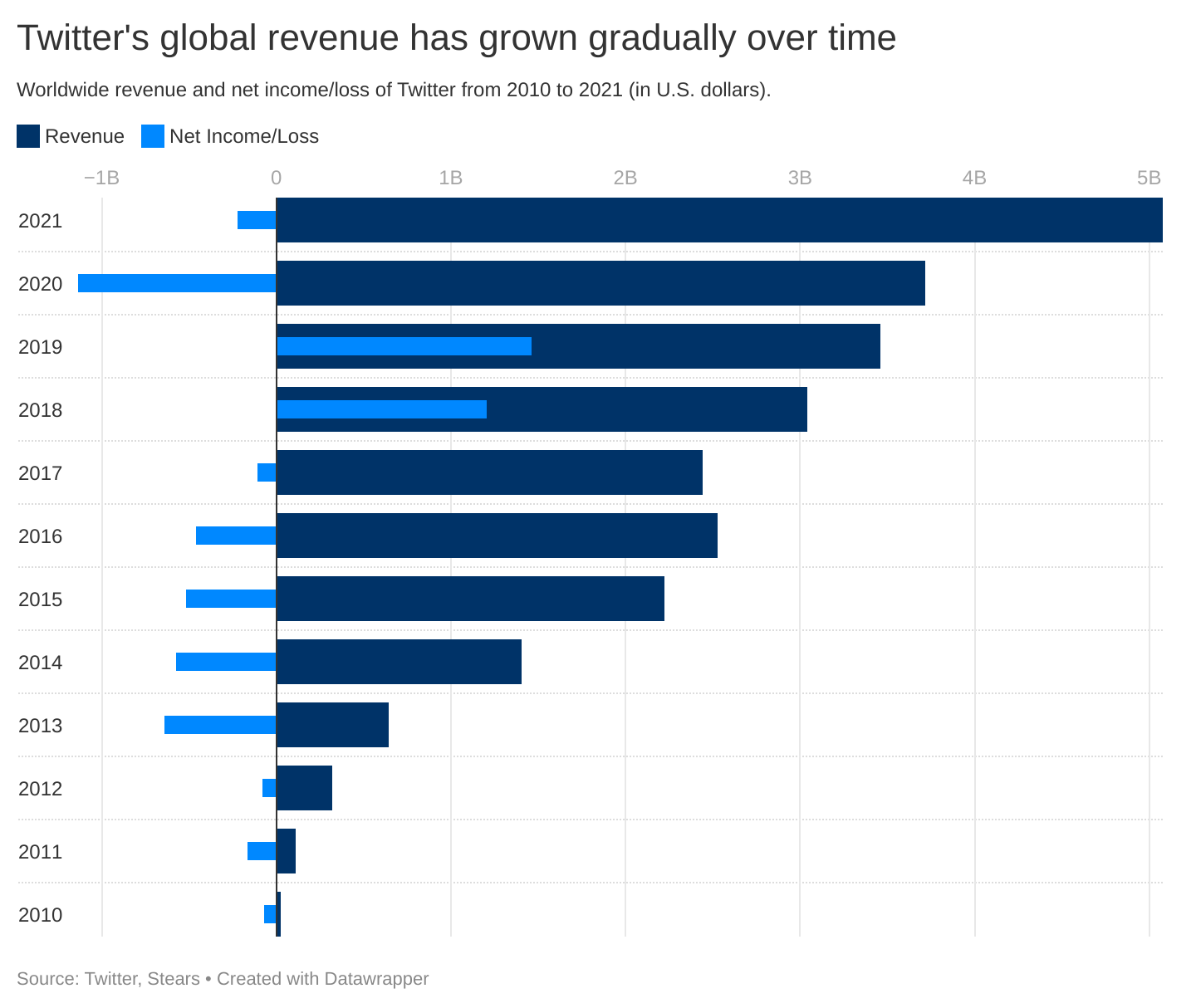

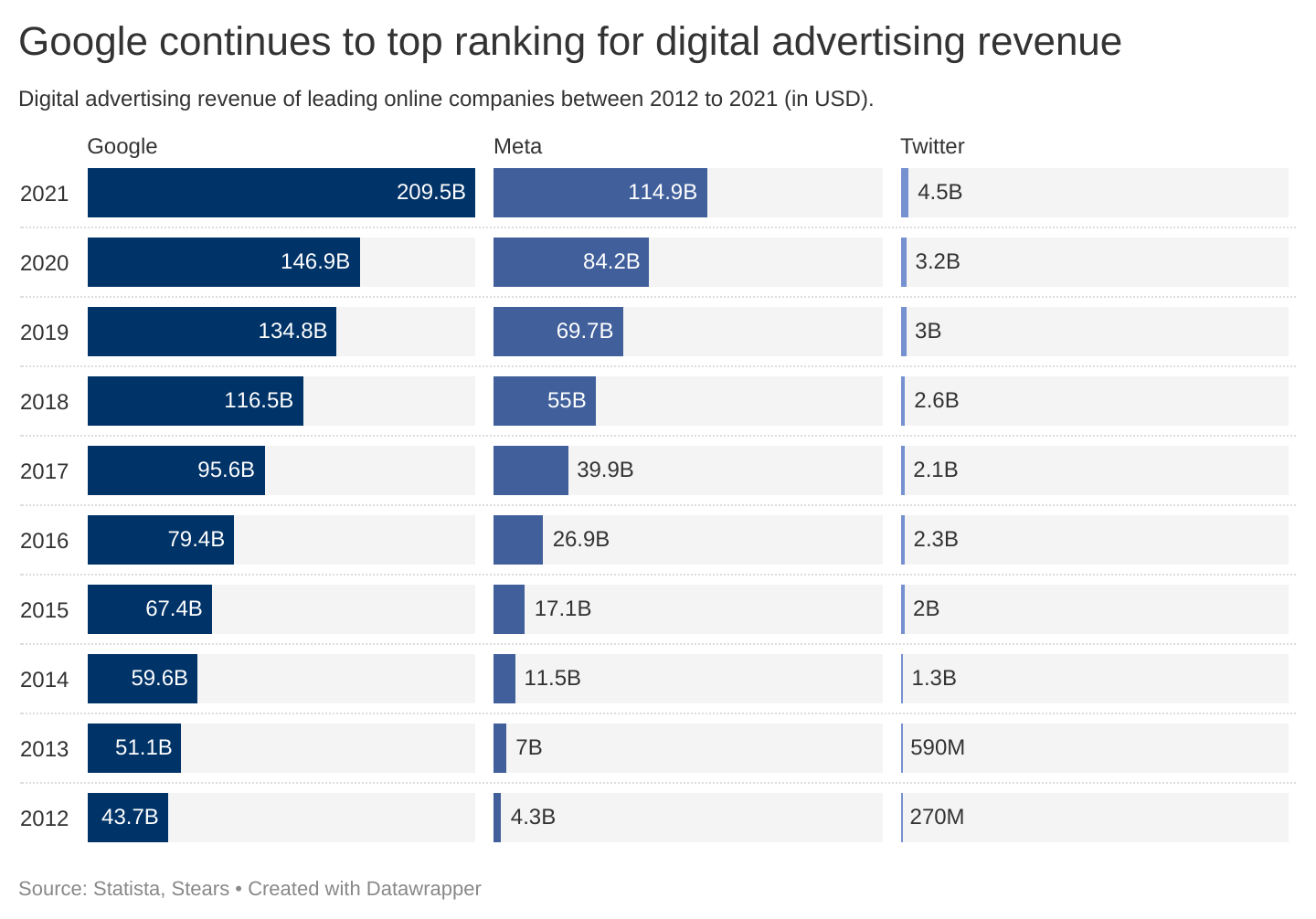

Over the last decade, Twitter has constantly been the subject of scrutiny for its weaker metrics compared to other social networks such as Facebook, TikTok and YouTube. Despite its growing revenue, which crossed a high of $5 billion in 2021 (with $4.5 billion in digital advertising revenue), the social network is not the success some of its investors expected—lagging behind in 2021 digital advertising revenue compared to Google ($209.5 billion) and Meta ($114.9 billion).

According to Chris Sacca, founder of Lowercase Capital, Twitter could have acquired and retained hundreds of millions of users if it made tweets effortless to enjoy, easier to participate in, and allowed everyone to feel heard and valuable. But whether you think Twitter has hit a plateau or is entering a new phase, its effect on celebrity, media, and political culture in just under two decades is undeniable.

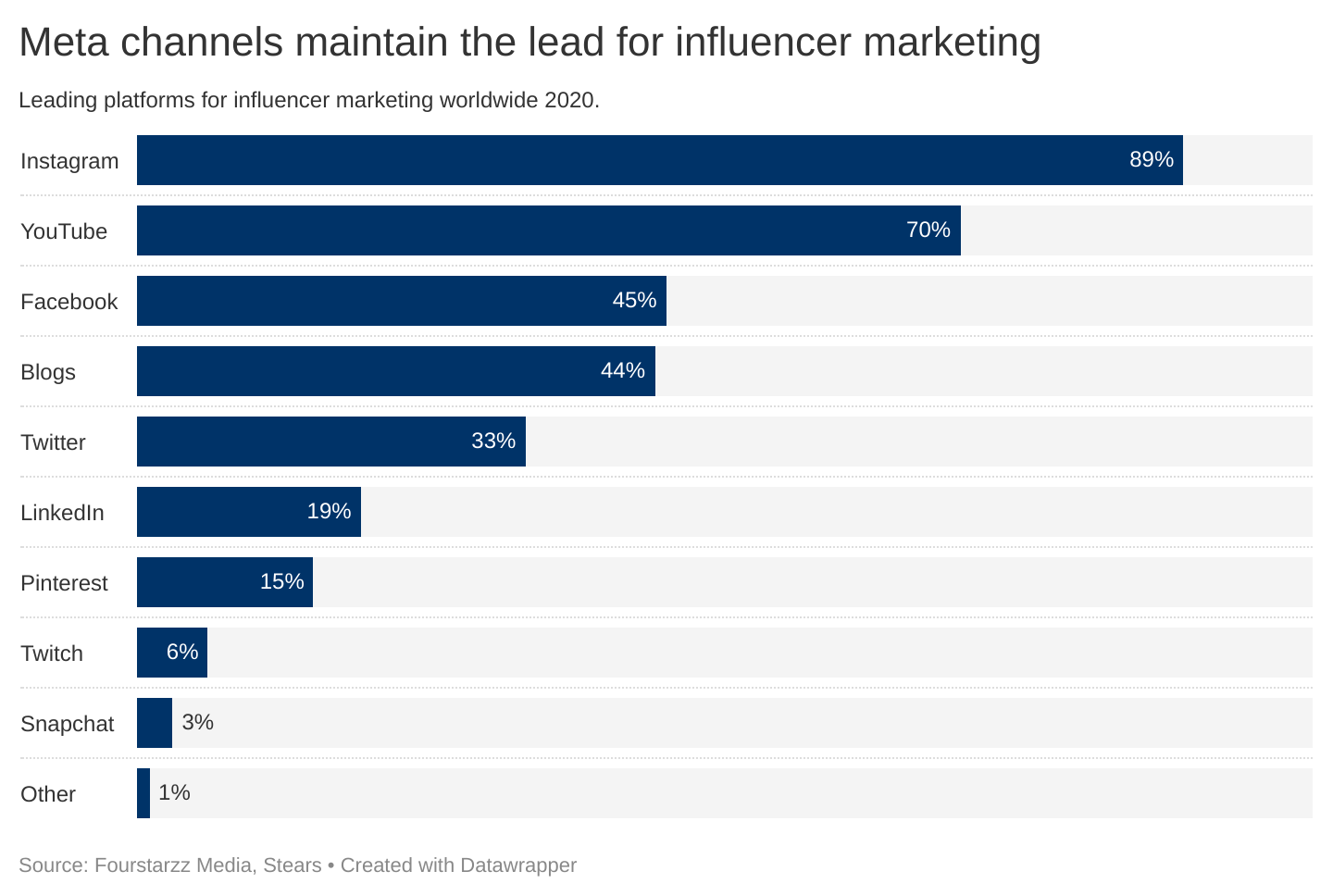

It has also indirectly propped up the creator economy with online platforms like Substack, Gumroad and Twitch, leveraging the platform for user traffic and growth. While the African continent still makes up a smaller proportion of global users, Twitter has, along with Meta and Google channels, provided a primary medium for content creators to build, engage and not necessarily monetise their fans.

A public town square or a high-school popularity contest?

From the start, Twitter has inspired polarised reactions.

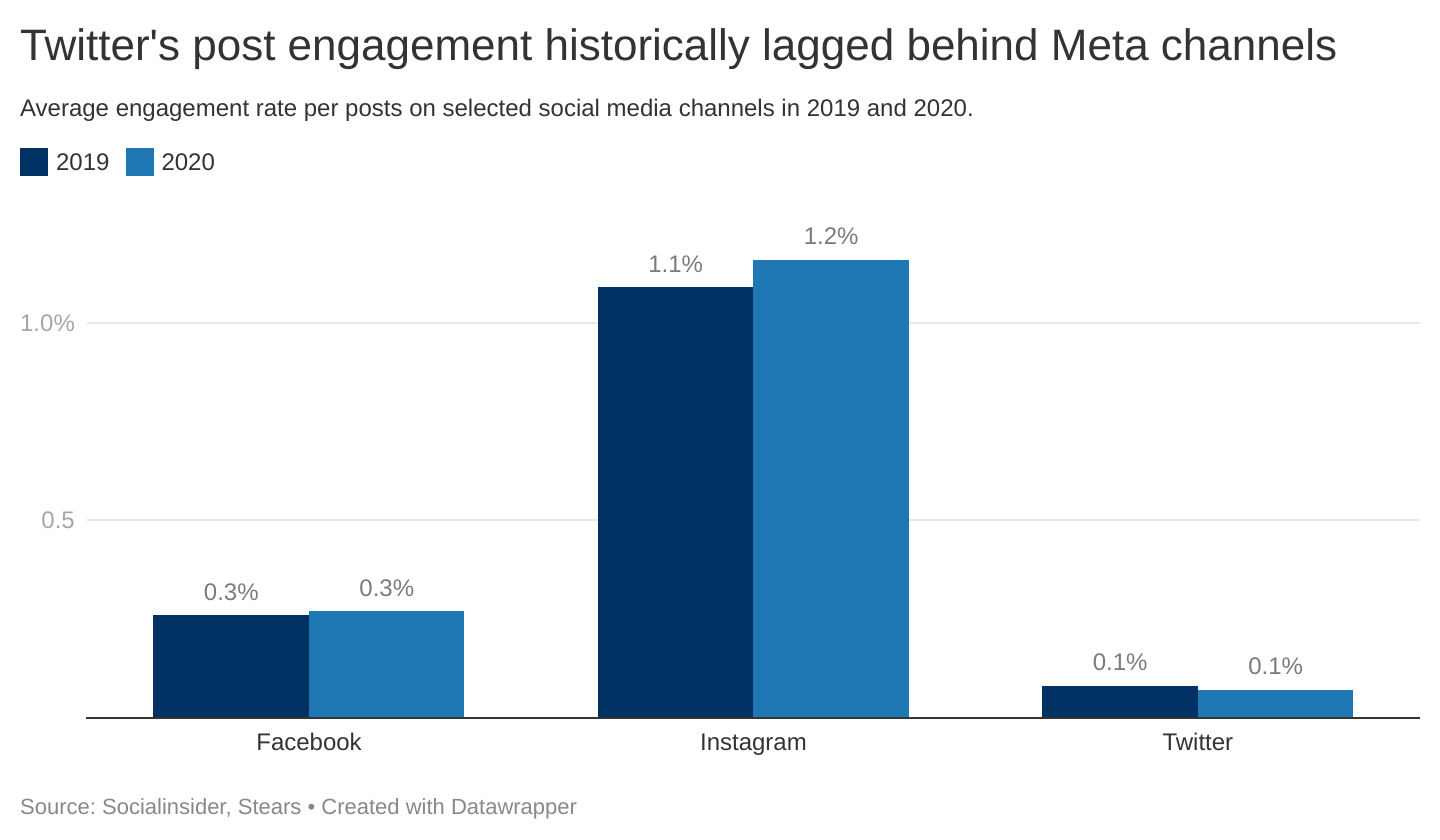

For many of its 436 million monthly active users, it is an addictive source of endless information. A virtual community where anyone can find the latest trends, get a pulse on various communities or push their opinions and agenda. For others, it is a place for trolls, narcissists and shameless self-promoters alike to battle out their irreconcilable differences. However, taking the high road and becoming a passive observer on the platform also creates a sense of FOMO. Some users report that it can sometimes feel like shouting into the void if you don't have a solid follower base. As the platform’s post engagement (0.1%) has historical lagged behind Facebook (0.3%) and Instagram (1.2%), this might explain part of this.

The feeling of constantly engaging or being irrelevant creates both "addiction" and "anxiety". These two words characterise the relationship with Twitter for many users because it feels unhealthy to invest so much time in a service that brings so much anxiety and stress.

As the Financial Times put it, it's as though Silicon Valley created something approximating a perpetual high-school popularity contest.

Another aspect of Twitter, which the company is still grappling with, is its role as a public town square, i.e. where people can gather to form ties around issues that affect them. It has created a free speech quagmire that has threatened governments and social groups alike.

In 2009, the idea of "Twitter revolutions" began with an uprising in Moldova around its elections and caught on during the Arab Spring of 2011. During the Arab Spring, the Egyptian government shut down the country's internet access for five days to stop protesters from co-ordinating online. Fast-forward to 2021, when governments like Nigeria banned Twitter from operating in the country. The ban, which occurred after Twitter deleted tweets by the Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari, was lifted in early 2022 following extensive lobbying by civil interest groups and Twitter.

But this hasn't been the platform's only use case.

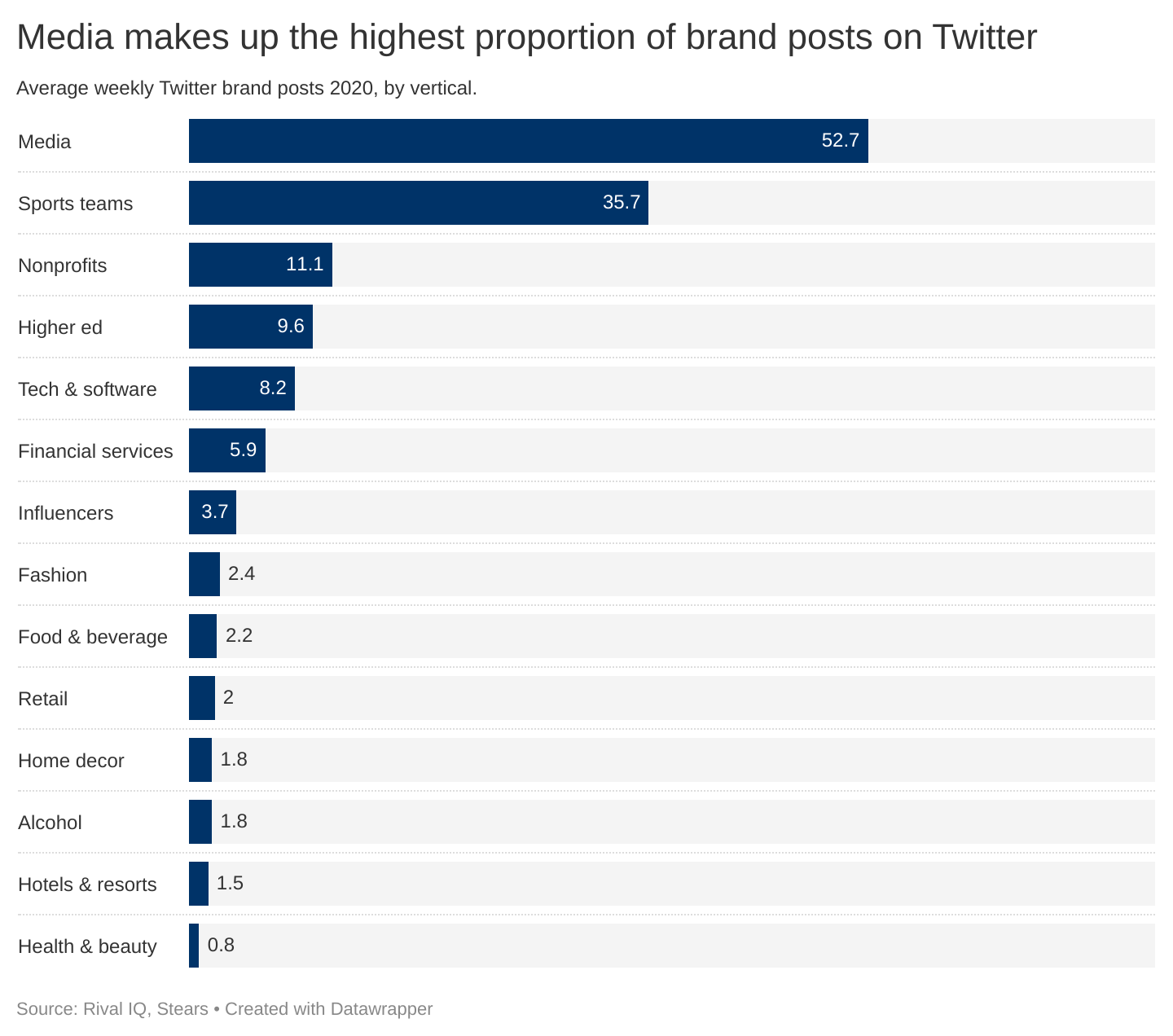

It has served as the perfect platform for some content creators and publishers to promote themselves, carve out their brand identity and engage with fans. Chief among these groups of creators have been media and news outlets.

However, Twitter has seen opportunities lost to other platforms servicing independent creators. For publishers who already had existing modes of monetisation, the platform is simply an advertising channel used to acquire users who engage with their content. But it has performed poorly for independent creators in the "creator economy" as it hasn't provided the infrastructure to monetise their offering effectively.

The idea of a creator economy is a relatively new concept.

According to SignalFire, the venture firm that invested in platforms such as Clubhouse, the creator economy is a class of businesses built by over 50 million independent content creators, curators, and community builders. This includes social media influencers, bloggers, and videographers, including the software and financial tools designed to help them grow and monetise.

In plain terms, these are self-employed individuals and businesses who make money through a knowledge/skill they offer or simply by entertaining people online—and the tools they use to do so.

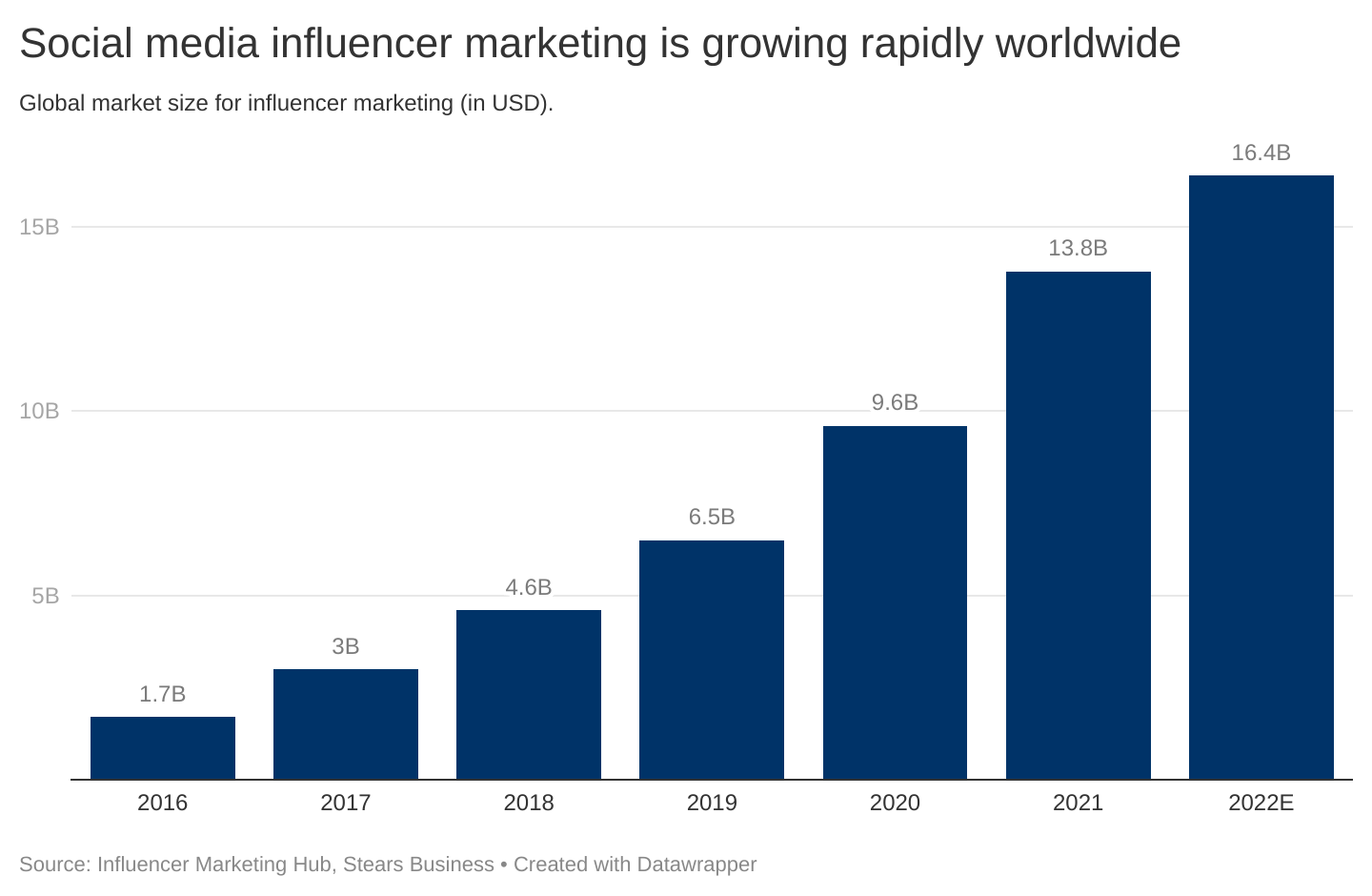

Combined, this industry is expected to grow beyond $100 billion in 2022. Of this, the influencer marketing industry—the creators themselves—should surpass $16 billion this year.

The creator economy represents part of a shifting paradigm.

It's disrupting existing industries such as entertainment and marketing. For instance, 3 out of 4 companies globally now intend to market through influencers in 2022, and of those that do, 68% plan to increase their influencer marketing spend.

But where does this leave Twitter?

Twitter wants to crack the creator economy.

During a Spaces conversation on February 10, Twitter Chief Financial Officer, Ned Segal, admitted that "a lot" of creators are on Twitter and use the platform to build their audience, but they go elsewhere to make money. He echoed the sentiment that the company needs to do a better job at helping creators stay on Twitter for "their customers' benefit, for their own benefit, for our benefit," Segal said.

The platform may still struggle to identify what it is and who for the average user, but it's a bit clearer for content creators.

There are two broad categories of creators you find on Twitter. First, the influencers provide users with entertainment through hot takes, quick-witted responses or memes. Second, you have the experts who try to share knowledge based on their expertise and experiences—think academic Twitter or the endless threads by VCs and start-up founders.

Sometimes these groups overlap, but expert creators trying to monetise their user base are often clear on what they offer to their fans. In particular, they have built their audience on Twitter, but to date, the company has not provided or shown creators the tools to own their audience or make money. That's why creators send their Twitter followers to other platforms—Substack, Gumroad, etc.—to monetise them, even though Twitter might have a competitive advantage for monetisation because it supports different types of content, e.g. tweets, blog posts, live audio and video.

The platform has been experimenting with avenues for people to make money through features like super follows, tip jars and ticketed spaces. However, according to Segal, the issue isn't that creators don't think they can get paid on Twitter. He believes that Twitter hasn't done a good enough job of saying there's a place for creators on the platform.

Over the last couple of years, the company has regularly shipped products and features to do two things; help creators monetise better and make Twitter feel a little smaller and less intimidating for users. It launched communities to allow users to tweet only to a group of people interested simultaneously and spaces for live audio conversations, which some believe contributed to Clubhouse's demise. It also started testing Flock, a way for you to tweet to your close friends and has been rolling out improvements to direct messaging.

The company also acquired Revue in 2021 with plans to tie the long-form newsletter platform to its own in the hope of using the additional features to help individuals follow writers, communicate with creators, and subscribe to their newsletters.

Shortly after the acquisition, Twitter attempted to incentivise creators to move to Revue by opening Pro features to all accounts and reducing the company's subscription take to 5%.

But every social media platform is trying to figure out how to appease creators. TikTok, Instagram, YouTube and even Pinterest are fighting for creators to use their short-form video tools, while Spotify wants all the audio creators.

From Segal's comments, influencers have not yet embraced Twitter's audio tools, and the company has only just started to play around with more video features. So it remains to be seen whether these changes are likely to attract content creators flocking to Substack, Medium, and Gumroad, especially if those content creators already have substantial Twitter followings.

Nevertheless, Twitter has made it clear that it's willing to pay creators. It just needs to figure out how and who.

And African creators?

Well, it's tricky.

So far, commission structures for content creators who rely on advertising have been based on the value assigned to their demographic by marketers, which significantly disadvantages African creators. It does create an opportunity to help creators on the continent capture more direct monetisation from their fans.

Youtuber Fisayo Fosudo (@Fosudo on Twitter) provides a good example. The young finance and tech product reviewer has a strong base of over 247,000 subscribers on Youtube. Fosudo explains that his monetisation strategy as a creator basically stems from 3 major sources; ads, brand partnerships and creative consulting—but brand partnerships comprises the major part of his income. In one of his posts, he explains that Google paid him more for a video on the Central Bank of Nigeria's decision to ban cryptocurrencies with 150,000 views, in contrast with an earlier video reviewing the Samsung Galaxy A10 with 700,000 views.

Why? It is all about advertising dollars.

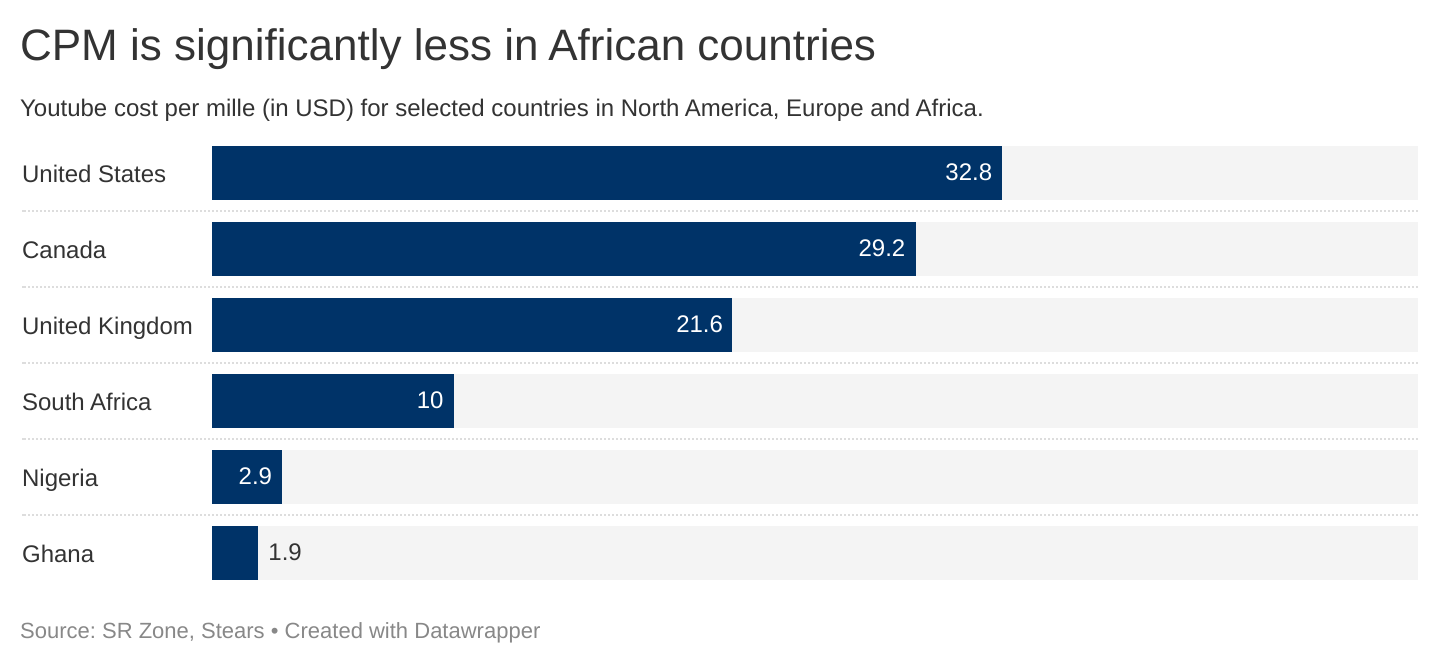

It all comes down to who watches your video and where they are based. Currently, Google's advertising algorithms are heavily skewed by the viewer's location—as well as interest to an extent—because your location determines the consumption power of your viewers and, in turn, the advertising dollars marketers are willing to spend. For instance, a popular Youtube channel on finance will likely earn more per view than a food channel in the same region because the finance sector has more advertising dollars. But, the same Youtube channel on finance will earn far less in Nigeria for the same content and engagement compared to Canada, where the cost per mille (CPM) is 10x that of Nigeria as competing advertising bids in North America are much higher.

CPM is effectively how much advertisers pay content creators per 1,000 views (and/or clicks). For instance, if you get 200,000 views and have a CPM that's $10.50, the video's total revenue is $2,100.

Half of the internet users on Nigerian e-commerce sites go on to make a purchase. However, they spend only a fraction of what's spent online globally, with an average revenue per customer of $96. Globally, it's over ten times this amount, at $1,017. This has implications for the brands that target these customers, the creators' bargaining power when negotiating, and how effectively creators can monetise them.

A way to mitigate this for African creators is by positioning themselves to attract a global audience to create more substantial bargaining power with brands and directly monetise their fan base. But the universal appeal is difficult to attain, especially when your region heavily influences your experiences and content.

Speaking with the Nigerian screenwriter and co-host of the popular I Said What I Said podcast, Jola Ayeye (@Jollz on Twitter), she notes that with their podcast, although the content may, in theory, be relatable to a broader global audience, it's still not easy to attract international listeners. Their appeal to local listeners (and perhaps the Nigerian diaspora) reflects a lot of the mannerisms and style you would expect in a casual conversation with Nigerians. It may be a little louder, at a faster pace, and a little more chaotic than listeners who aren't familiar with Nigerian culture can keep up with.

Ayeye, who also runs an online book club, added that she is generally hesitant to monetise content because she must consistently deliver high-quality content before considering it. Further, the primary options available for African creators primarily include brand partnerships and sponsorships. "Monetising [this way] is easy if you sacrifice your freedom," she jokes.

What she alludes to, though, is essential not just for choosing the right sponsors to partner with but also for what content creators produce and how to monetise their fans directly. For local creators who want to adapt their content to attract a global audience, a challenge is considering how it affects their existing brand positioning—but that's for the creators to figure out.

On the other hand, Twitter has a product issue to fix that could potentially create a new market for African creators.

It should be easier for a global audience to find local content on the platform. The success of Mark Angel, Nigerian producer of the globally-acclaimed YouTube comedy series Mark Angel Comedy should be less of an exception for African creators.

Both Ayeye and Fosudo iterate the view that Twitter has amplified their voice, helped cultivate their following and indirectly led to monetisation. They’re fans of the social network and appreciate the opportunities it provides to learn and connect with potential collaborators.

Yet, it could be so much more for them.

By unlocking the discovery opportunities on the platform, Twitter opens up the world and itself to new content lines that are local but relatable across global communities. Admittedly, African users make up a smaller proportion of Twitter users compared to North America and Europe. However, what African creators need isn't necessarily more fans in Africa but fans worldwide that get them paid. Mainly to communities where spending power is more substantial, and it's easier to export their content.

Chris Sacca got a few things wrong about the future of Twitter back in 2015—apparently, Periscope was meant to be a game-changer for the company, but alas, it wasn't. However, an area that he rightly identified, which many new users continue to struggle with, is the high barrier to entry and discovery on the platform.

Unlike Meta (Instagram) and TikTok platforms, which appear to have hacked the algorithm to reduce this barrier, Twitter users often require more effort to discover the content they like and find the communities they want to be part of. It makes the platform less sticky for new users but leads to high switching costs for those who have overcome the barriers.

Easing this barrier for new users to engage without compromising the influence power users have built will be necessary to fix this problem.

For now, Twitter users may be at the mercy of Musk.

And like the company's Board on January 30, 2022, a day before Musk started building his stake in the company, it's hard to predict how this will play out. For one, with Musk at the helm of the social media platform, it may lose its appeal to certain users, which could be a good or bad thing depending on how you look at it.

Perhaps the platform becomes flooded by Musk fans who adore his chaotic brand on Twitter? Maybe more the civic-minded users might object to his control and boycott the platform? These may not be bad for the company's bottom line if a core base of its users and creators keeps growing and engaging with the platform.

It just might not be as fun for the rest of us.