It’s open season on Shell, Exxon Mobil and Chevron assets as they divest from Nigeria’s onshore and shallow water oil assets.

Onshore oil assets are found on land, while shallow water assets are found underneath bodies of water less than 150 metres deep. Therefore, extraction and production occur on land or shallow water (creeks). However, international oil companies (IOCs) are still keeping their deep offshore assets found at sea.

Key takeaways

-

Due to Nigeria’s high-risk oil and gas industry, international oil companies like Shell and ExxonMobil are divesting from Nigeria’s onshore and shallow water oil assets.

-

Local oil companies are first in line to acquire these assets thanks to the local content act, but the financing structures we’ve seen have been aimed at attracting a diverse pool of investors.

- Due to significant risk factors in both the global and Nigerian oil and gas industries, we expect more innovative finance structures

Thanks to the local content act, this is good news for local oil companies that top the list of prospective buyers. The local content act aims to increase Nigerian oil and gas industry participation by setting minimum thresholds. Nigerian companies have a fair shot at increasing operations and playing more significant roles in the oil and gas sector thanks to the act. This means local companies like Seplat and Sahara energy can increase their oil production and revenues to contribute more meaningfully to the Nigerian economy. Additionally, these expansions could create more job opportunities for Nigerians as local companies are more likely to employ local talent and empower more Nigerians to attain high ranking positions in the oil and gas industry.

Naturally, Nigerian oil companies have reported acquisitions of assets and shares of international oil companies (IOCs). Last year, in January 2021, the Trans-Niger Oil & Gas Limited (TNOG) and Transcorp plc, owned by Nigerian billionaire Tony Elumelu, acquired 45% of OML 17 (an oil block) by buying up stakes from Shell (30%), TotalEnergies (10%) and Eni (5%). And this year, Seplat announced that it was in the advanced stages of acquiring the entire share capital of Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited (MPNU), Mobil’s onshore unit, from Exxon Mobil.

Essentially, it’s acquisition season in the Nigerian oil and gas industry. Interestingly, there have been quite a number of popular acquisitions and acquisition rumours recently. From Elon Musk’s on-again, off-again Twitter acquisition to Chelsea Football Club’s and even Zinox’s rumoured interest in Jumia, the dynamics can differ from deal to deal. On the surface, acquisitions happen when one company purchases most or all of a company’s shares or assets. But, digging deeper, the dynamics vary depending on the reasons behind the acquisition and even the players' industries.

Consequently, we need to understand the dynamics of acquisitions in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry, mainly as it affects available funding, and what we can expect from future acquisitions.

Nigeria’s risky oil and gas industry

Elon Musk’s Twitter takeover journey has been dramatic, to say the least. Right now, we’re not even sure he’s going to go through with it, given his latest shenanigans around spam accounts.

Thankfully, the acquisitions in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry shouldn’t be anything like Twitter's. For one, they aren’t hostile. International oil companies (IOCs) are voluntarily exiting, and selling off their assets and shares is how to achieve this exit.

Amid an oil price boom, they're leaving because of how expensive it has been to operate in the Nigerian upstream sector. Vandalism, oil theft, and operation shutdowns have become the norm, and the margins aren’t worth it for IOCs.

You’re probably wondering why Tony Elumelu’s TNOG or Seplat would want to wade in Nigeria's oil assets' murky onshore and shallow waters. The reason is that while the margins aren’t significant for IOCs, they’re adequate for local oil companies. You see, the IOC business model is hinged on economies of scale. Economies of scale mean that a company performs better and its costs are lower when production is increased.

In the oil and gas industry, the commercial viability and feasibility of projects majorly depend on the economies of scale. Crude oil production is a high-risk endeavour. It requires initial investments that run into millions of dollars, and these investments do not guarantee that commercial volumes of oil will be found. Companies have invested millions into wells without producing any oil in the end. So, the higher the expected volume of reserves, the higher the investment companies are willing to make. Higher volumes translate to higher profits and lower costs per unit.

IOCs operate hundreds to thousands of oil assets worldwide. Their investment decisions are based on the projected reserves and forecasted oil prices—the two factors that determine revenue. Other risks with oil production include price risk (oil prices are volatile), and stakeholder risk (interfacing and getting agreements from host communities, governments, regulators, etc.).

This affects Nigeria because while IOC-owned oil reserves are promising and oil prices are high, the added risk of theft and vandalism has increased the cost of producing oil in Nigeria. With vandalism being the leading cause of production shortages in Nigeria, it’s a high-probability, high-impact risk.

The Nigerian asset margins aren't commercially viable for IOCs with billion-dollar assets worldwide with better margins. Also, with the pressure to transition to clean energy sources, IOCs are prioritising relatively low risk, high margin investments. Essentially, IOCs have a wide range of investment options with better returns that they don’t have to deal with Nigeria’s issues. For instance, Shell’s Nigerian production in 2020 from onshore and offshore assets was 223,000 bpd on average, but this dropped to 175,000 bpd in 2021, a 21% drop year-on-year. For context, in 2021, Shell produced about 615 million barrels, an average of 1.7 million bpd.

On the other hand, lower production volumes are still viable for relatively small local oil companies. And while the risks are still high, oil production is still profitable even with smaller volumes, so the risks aren’t deal-breakers. For instance, Seplat’s acquisition of MPNL will bring up production capacity to 146,000 barrels per day, still a fraction of Shell’s global production.

These acquisitions are significant for local oil companies. They allow local companies to grow their production capacity and increase revenues when oil prices are over $100 per barrel and show no signs of declining.

So far, the TNOG OML 17 block acquisition is the only closed deal announced since the recent spate of IOC divestments. It’s a $1.1 billion deal, and the biggest acquisition in Nigeria since 2014, when Oando completed a $1.5 billion acquisition of all ConocoPhillips’ Nigerian assets and Aiteo acquired Shell’s OML 29 stake for $2.7 billion in the same year.

But, the global oil and gas industry has come a long way since 2014. Before we unpack what has changed, we need to understand the dynamics of recent acquisitions.

Luckily, the details of TNOG’s OML 17 acquisition are publicly available.

Following the money

The TNOG OML 17 block acquisition structure aims to reduce risk and maximise returns.

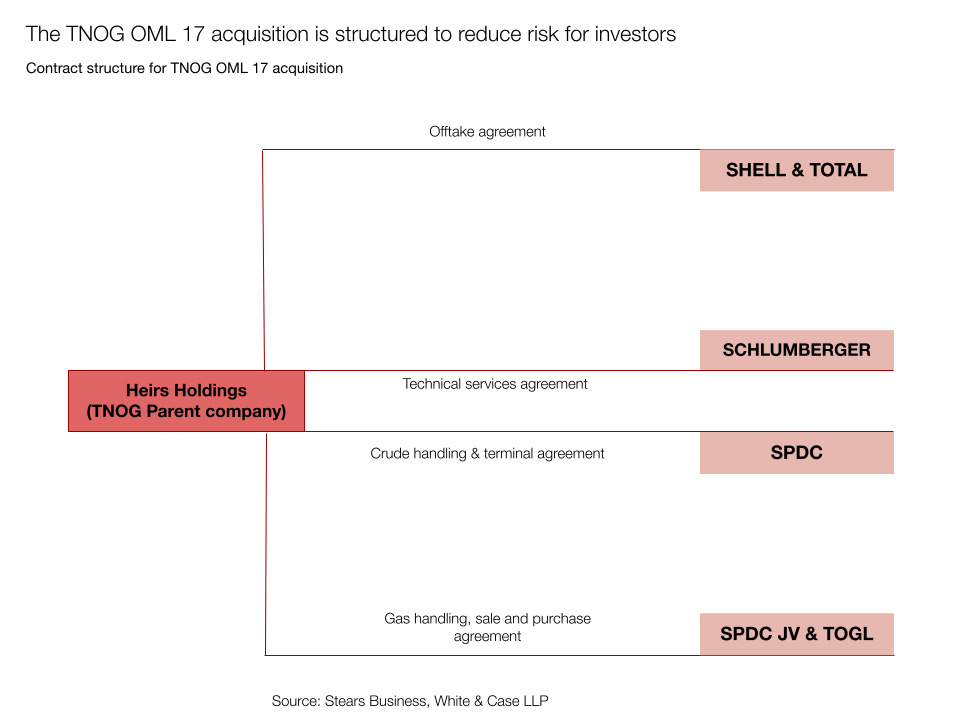

First, the acquisition involved TNOG finalising contracts with a buyer, a company that would buy the oil produced. In this case, the buyers were Shell and Total. It also required an agreement with Schlumberger, where Schlumberger would offer technical support services to enable TNOG to optimise operations. TNOG also had to enter a deal with SPDC, Shell’s Nigerian onshore company and the seller, where TNOG would be charged a tariff to use the Trans Niger Pipeline. Lastly, a gas purchase agreement was signed with SPDC and TOGL to purchase gas produced.

These contracts ensure that the deal is secure from the beginning (production) to the end (sale). So, for an investor who might have worries about the feasibility of the project, you know already that even though TNOG is relatively new to the oil sector, they have Schlumberger as a strategic partner to optimise production. You also understand that Shell owns a pipeline to transport the oil, so the infrastructure is sorted. Finally, you know that there are contractually obligated buyers for the oil and gas produced.

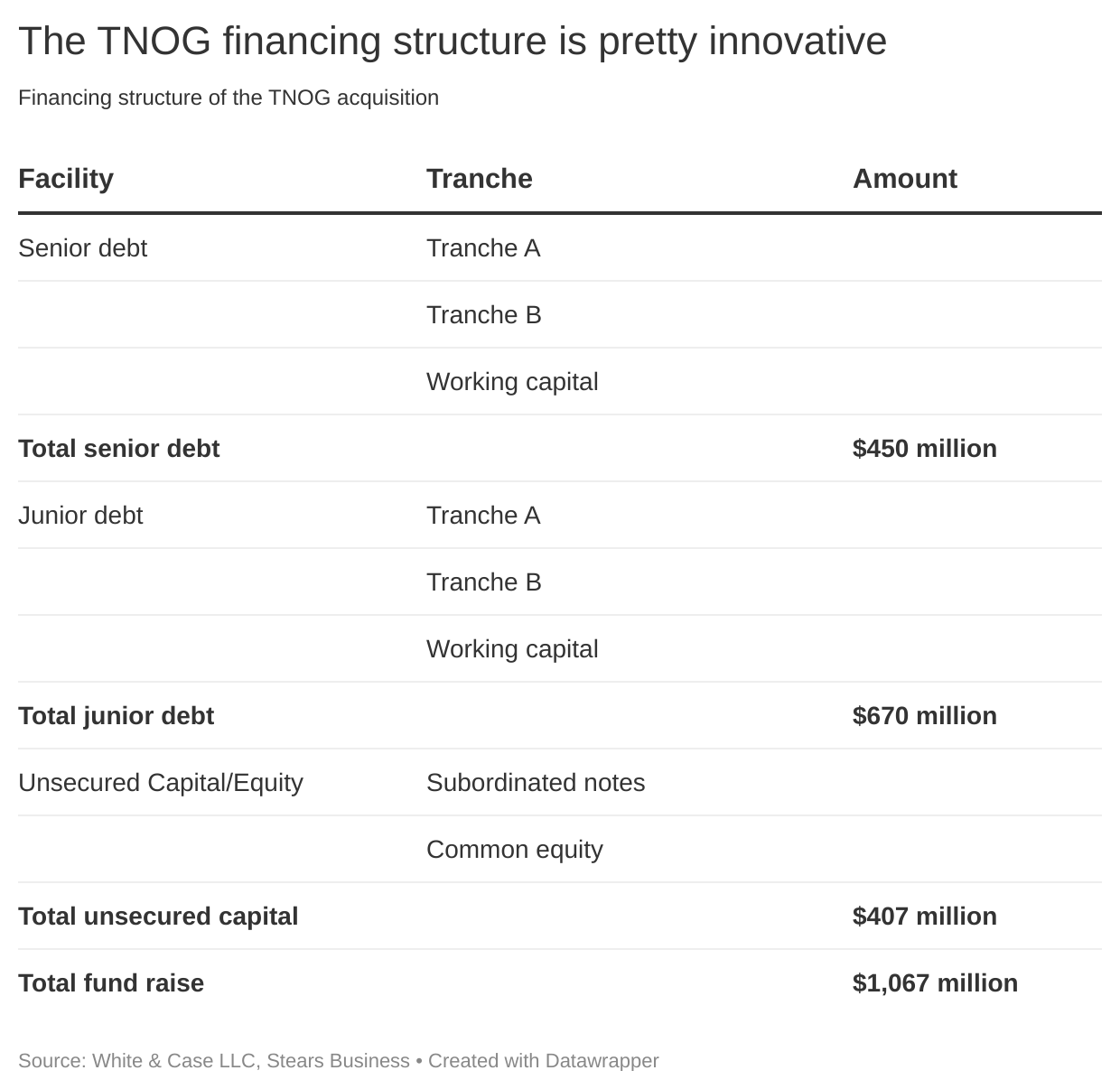

Then there’s the financing structure. According to White & Case LLP, the financing structure was highly innovative. I’ll provide a brief overview for the finance buffs.

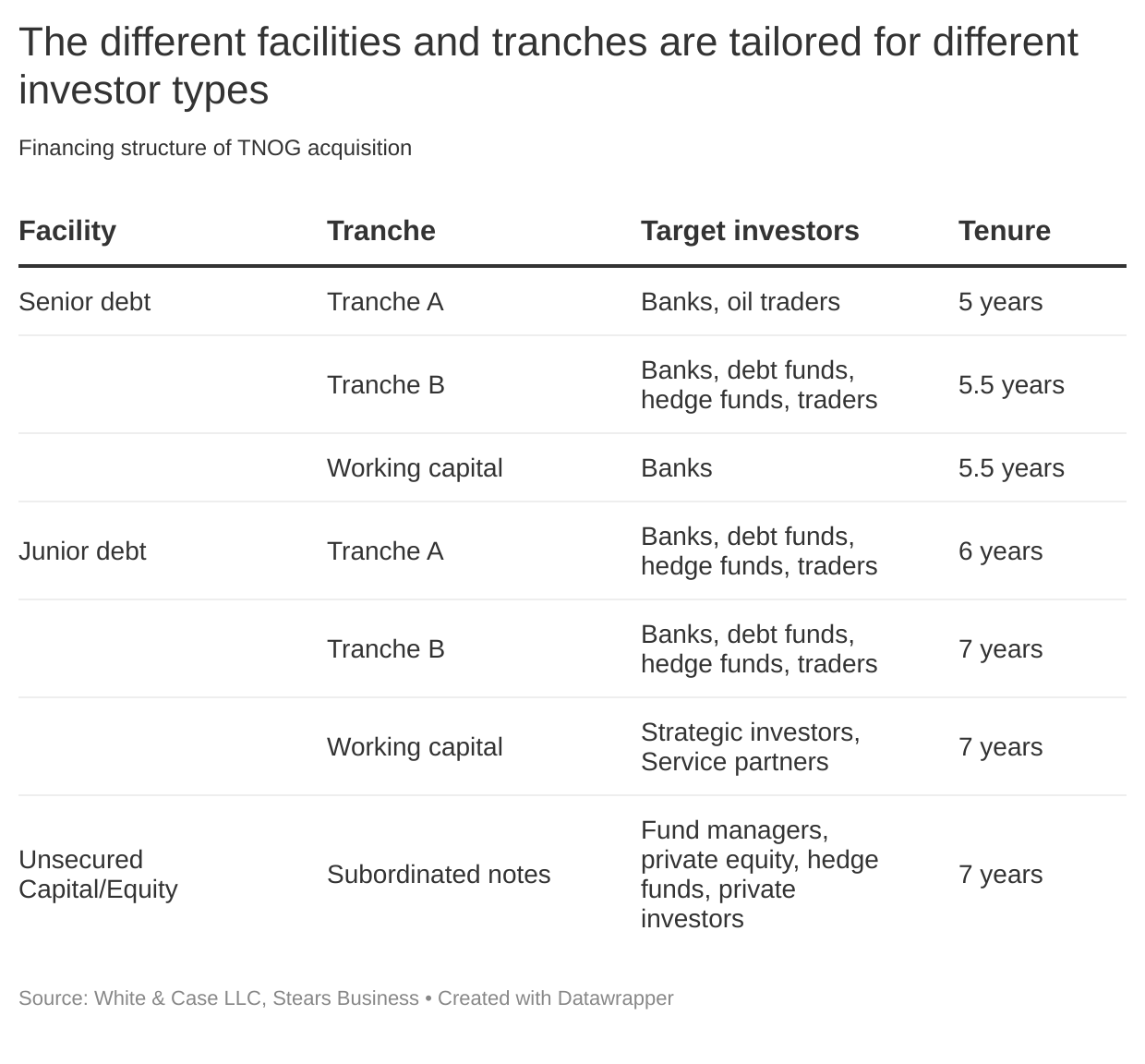

For people who aren’t in finance, what’s important here is that the debt is ranked in order of priority and risk, also known as a payment waterfall. The payment waterfall determines the creditors' rights and negotiating positions and reflects the ranking of the different loans. Senior debt gets paid first, then junior and finally unsecured capital. Also, the higher the rank, the lower the risk, which means lower interest rates and shorter tenures.

The structure of the financing is also in tranches. A tranche is simply a collection of loans that can be split up and sold to different investors. So, there’s senior debt tranche A and tranche B, junior debt tranche A and B. But each tranche has a different set of creditors. For instance, senior debt tranche B in this deal has diverse creditors like banks, hedge funds, debt funds and traders.

The same goes for every other tranche. Each tranche has specific characteristics that appeal to different investors. For instance, a relatively risk-averse investor looking for a short tenure will buy into senior debt tranche A. With the payment waterfall arrangement, this investor will also get paid first if there’s a default on the loan. A default on the loan could happen if TNOG goes bankrupt. In this case, senior debt A investors are sure they’ll be paid after TNOG’s assets are sold. But, a junior debt lender will have a higher interest rate, longer tenure and a higher risk of not getting paid if there’s a default on the loan. Simply put, investors need compensation for taking more risk, so the less senior the debt, the higher the interest rate. And for unsecured funding, these have the highest chance of not getting paid if there’s a default.

Why’s the debt structured like this? The primary reason is to attract a wide range of investors with varying risk appetites. The biggest lender in the TNOG deal is AfreximBank, with a $250 million senior debt tranche A loan, making up roughly a quarter of the $1.1 billion deal and over 50% of senior debt. AfreximBank is essentially a development finance institution (DFI) with a mandate to finance and promote trade within and outside Africa. Other lenders include Africa Finance Corporation (AFC), Union Bank, Shell, Hybrid Capital (an investment management firm) and Schlumberger.

So we’ve broken down the intricacies of the financing structure. We can now unpack the implications and why the financing structure needs to be innovative.

What are the implications?

We’ve said that the debt was structured this way to attract a wide range of investors. But why do oil and gas companies need a wide range of investors?

Before the recent price boom, the oil investment scene hasn’t been so hot. One primary reason has been the increasing popularity of activist investor tendencies toward preventing climate change. Investment banks, development finance institutions, and other lenders had either exited the oil sector or wound down on existing portfolios while rejecting any new business opportunities. The Covid-19 shock to the oil sector (where oil prices hit sub-zero prices) also didn’t help matters, and globally, oil investments shrunk.

This means that there are (or should be) fewer investors interested in oil financing activities. But this creates an opportunity for other non-traditional investors that you wouldn’t ordinarily see in oil and gas transactions. While some investors are still committed to oil and gas, others are still cautious.

On the one hand, commodity prices are fantastic, and oil and gas companies globally (except the NNPC) are swimming in dollars. But, oil prices are known for their volatility. While prices are expected to be high for a while, we don’t know how long this good turn will last. However, one clear thing is that to prevent an economic recession, oil prices need to be stable, and that requires some level of investment to bridge the supply gap caused by sanctions on Russian oil exports. For instance, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management firm with over $10 trillion in assets, consistently aligned investments to climate goals. But now, their new stance is that they will not support most climate change resolutions because the Russia-Ukraine crisis has highlighted the need for more short-term investment in traditional fuels to prevent an energy crisis.

This is good news for the global oil community. But, on the other hand, location matters. Remember, oil and gas returns are driven not only by price but also by volumes, and while prices are globally determined, volumes are not. Hence, regions or locations with high volumes will attract more investors. For Nigeria, oil theft and vandalism are significant issues that have caused wariness from foreign investors. If I were an investor, I would be cautious about how TNOG would be able to deal with vandalism and theft, especially given the government’s lacklustre response so far. Even Tony Elumelu has publicly shared that 95% of production is lost to oil theft and vandalism.

It also doesn’t help that local banks have said that it will be difficult to raise financing for these deals given that foreign currency is required. Due to lower oil revenues and the CBN’s forex stance, Nigeria's foreign exchange earnings have been lacking. The GT Holding company CEO said in September last year on the issue of raising money for oil and gas acquisitions: “when I look at the books of Nigerian banks today, I don’t see a lot of dollar liquidity. It is becoming a very difficult deal for people to pull off.”

It’s acquisition season in the Nigerian oil and gas industry as more local players take control of Nigeria’s assets. But while oil prices and a global energy crisis might be attracting investors, Nigeria’s high-risk industry and lack of local lending capacity is still a significant blocker.