What is the digital economy, and what powers it?

These are some of the questions the Estonian government tasked itself with back in the early 90s as it set on a mission to be the “world's most digitally advanced society.” Today, the country is hailed as the role model for governments, “where almost every bureaucratic task can be done online.”

It’s what countries around the world tapping into the opportunities presented by the digital revolution arguably aspire to or borrow from.

Key takeaways

-

Innovations in the digital economy are changing conventional notions about how businesses are structured, interact and how consumers obtain services, information, and goods.

-

A recent report by the World Bank estimates that by 2025, the resulting impact of the internet economy could contribute nearly $180 billion to Africa’s economy.

- Traditional economic statistics are not equipped to capture the nuance of how digitisation impacts economic activity in Africa,

Yet, the digital economy remains elusive and hard to grasp. This underlies numerous discussions at the Stears’ Technology, Innovation & Digital Economy sessions—as the digital economy is a tricky one to pin down, even for economists.

As our Head of Intelligence, Michael Famoroti, notes, it’s hard to pin down a widely accepted definition of the digital economy. Only the telecoms and ICT are formally captured in the GDP measurement in Nigeria. Many other sectors, such as fintech, are subsumed into their traditional industries, i.e. finance, making it difficult to identify their contribution.

Even trickier, elements of digital society, which include governance, security, identity and regulation, are not even reflected in any measurements. He adds that it is unclear how these should be reflected, but we need to account for them as they create economic value. Digital media alone consumes a growing part of our waking lives. Still, these go largely uncounted in economic metrics—think of the value gained from digital tools like Google and Wikipedia. That’s because the measure is based on what people pay for goods and services.

If something has a price of zero, it typically contributes zero to GDP—with certain exemptions.

Today, we focus on a narrow part of the broader digital economy, i.e. how do we measure or capture its contributions, because it matters for making the right decisions and investments in the future of a business, government or people looking to capitalise on the digital revolution.

It is common to find data supporting or negating the potential of African economies to take advantage of the global digital boom. One example is that of the top 20 fastest-growing countries globally, 19 are in Africa, with projections indicating that by 2050 the continent will have a total population of 2.5 billion.

This screams talent!

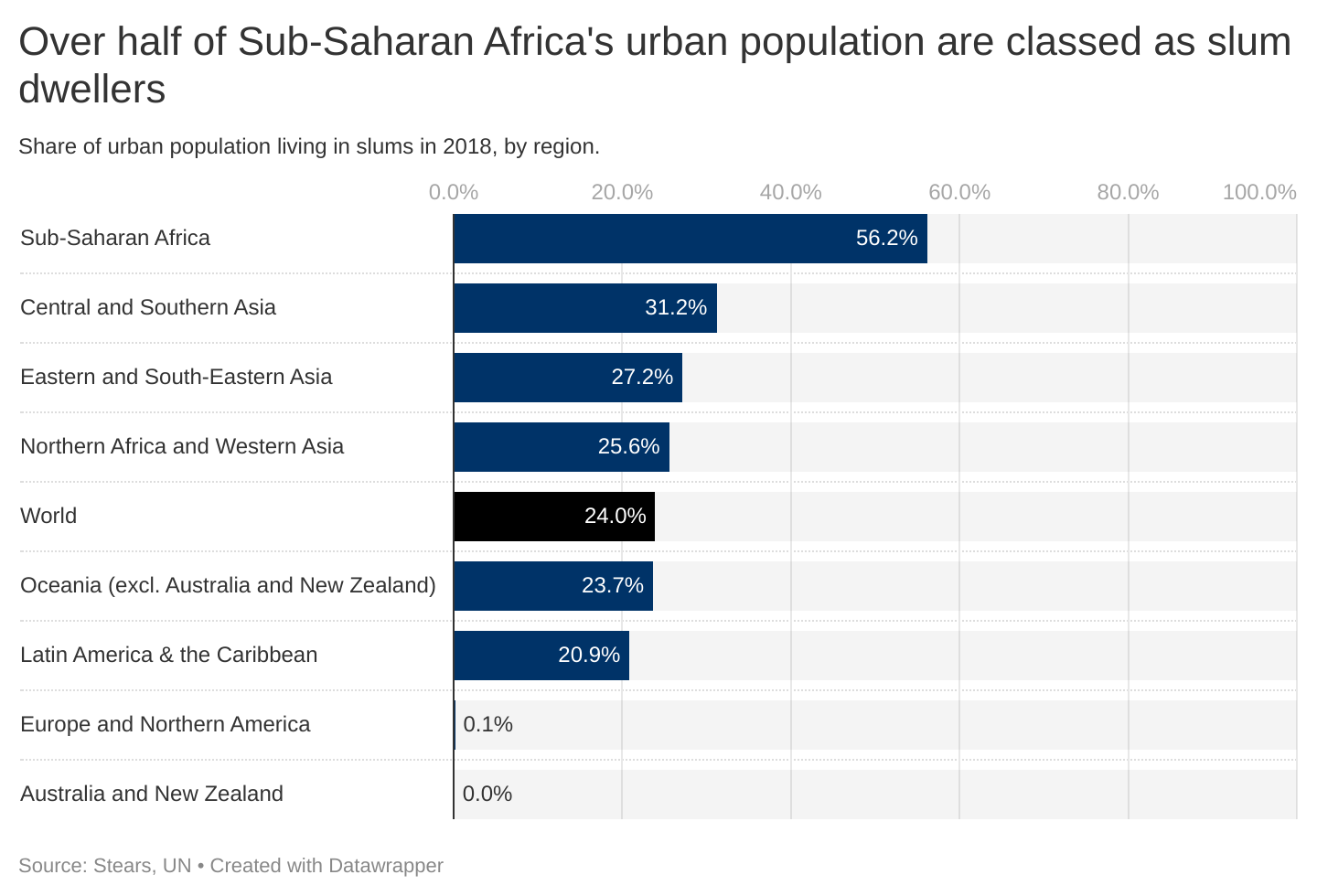

In contrast, reports also that suggest around half of the Sub-Saharan African urban population live in areas classed as “slums” by the UN.

These data points don’t adequately capture the nuance of how digitisation impacts economic activity in Africa, and bad decisions or policies are made with a poor understanding of reality.

To overcome this, we take a step-by-step approach to understand challenges with existing economic statistics for measurement, its impact on business decisions, and provide mental models to assess the opportunities presented.

So, what is the digital economy?

Although the term “digital economy” has existed for decades, it has taken on a new meaning in the last few years.

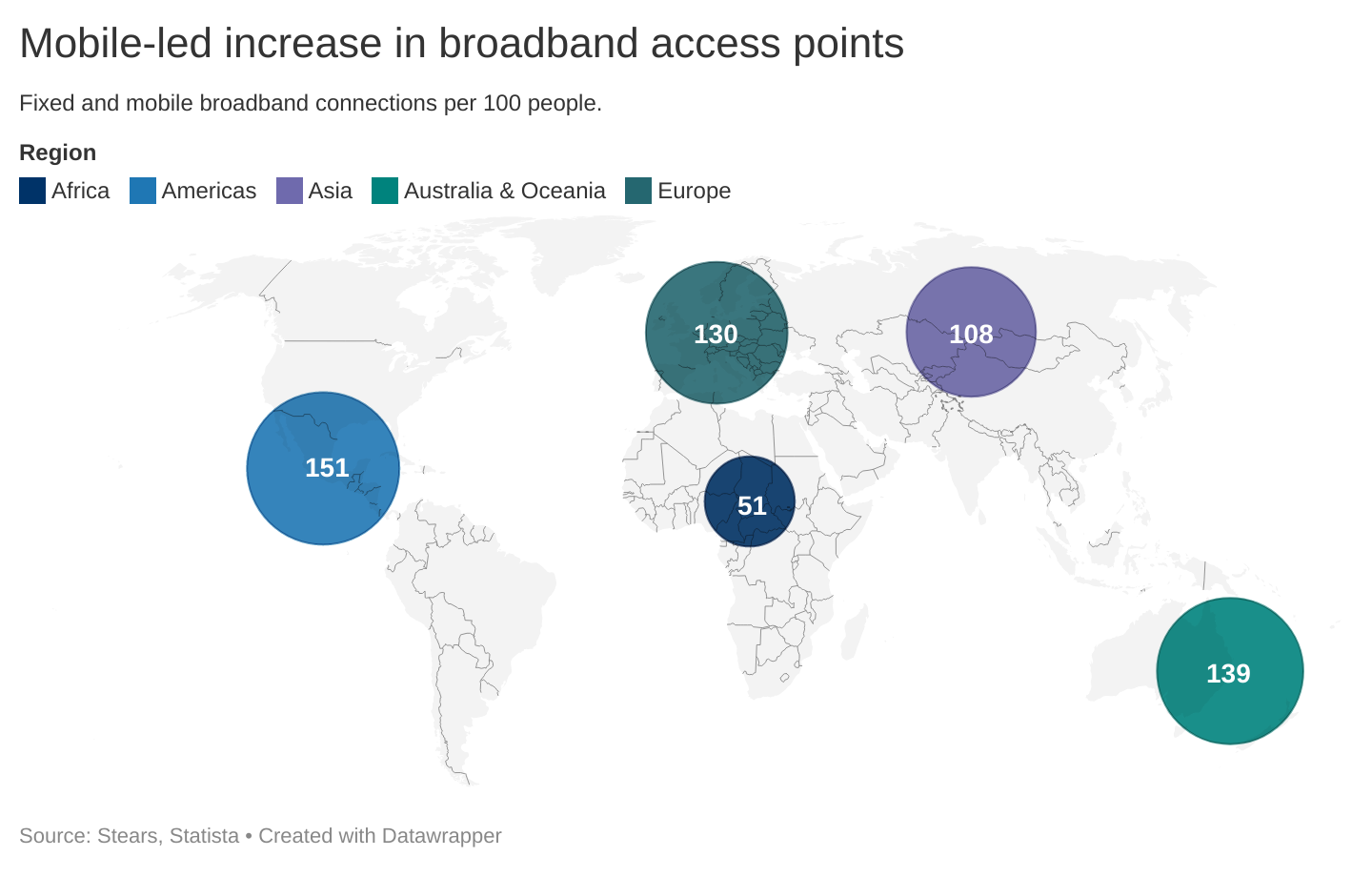

It captures all economic activity that results from billions of daily online connections among people, businesses, devices, data, and processes. The backbone of the digital economy is connectivity which means the growing interconnectedness of people, organisations, and machines due to the internet, mobile technology and the internet of things (IoT) drive the growth of the digital economy.

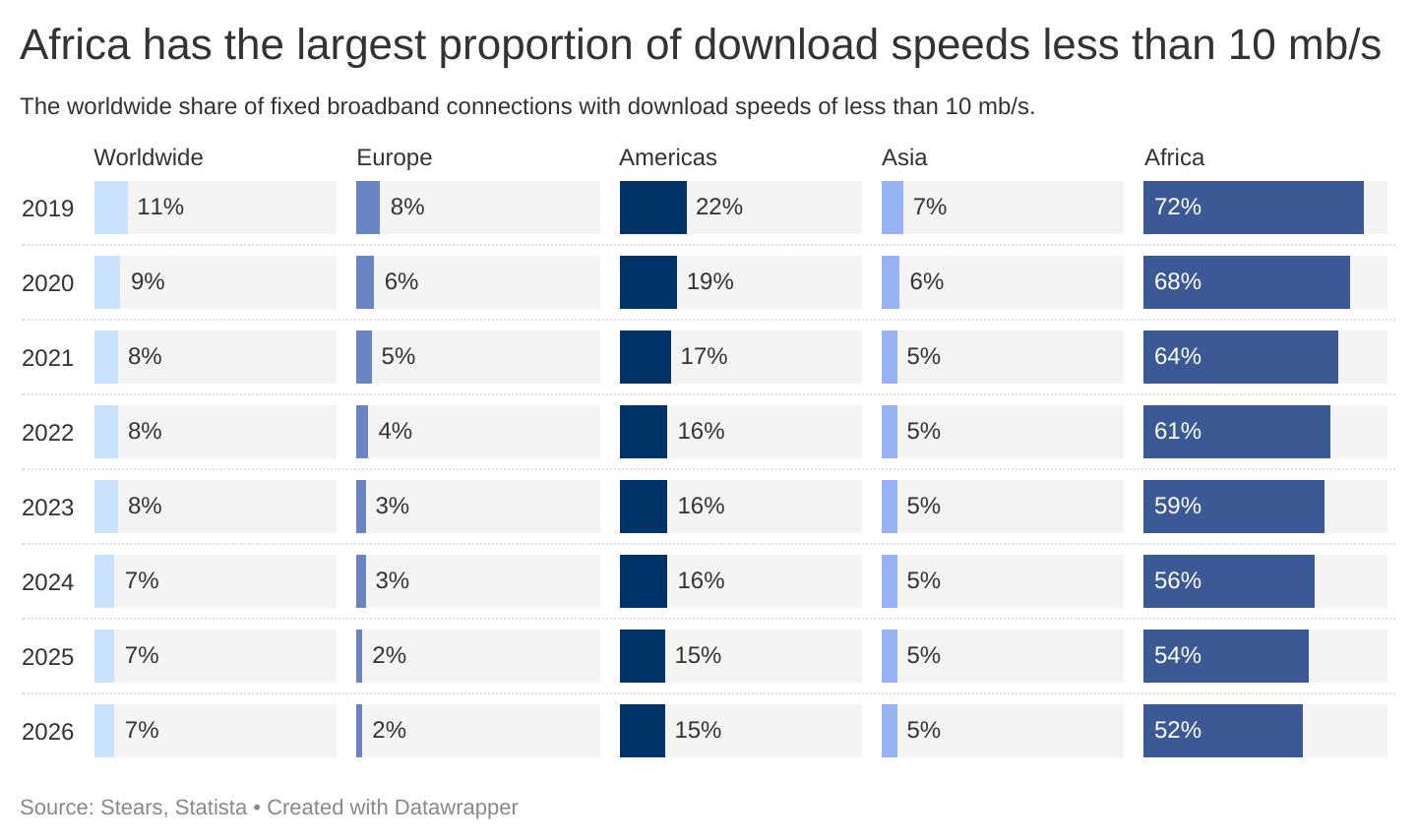

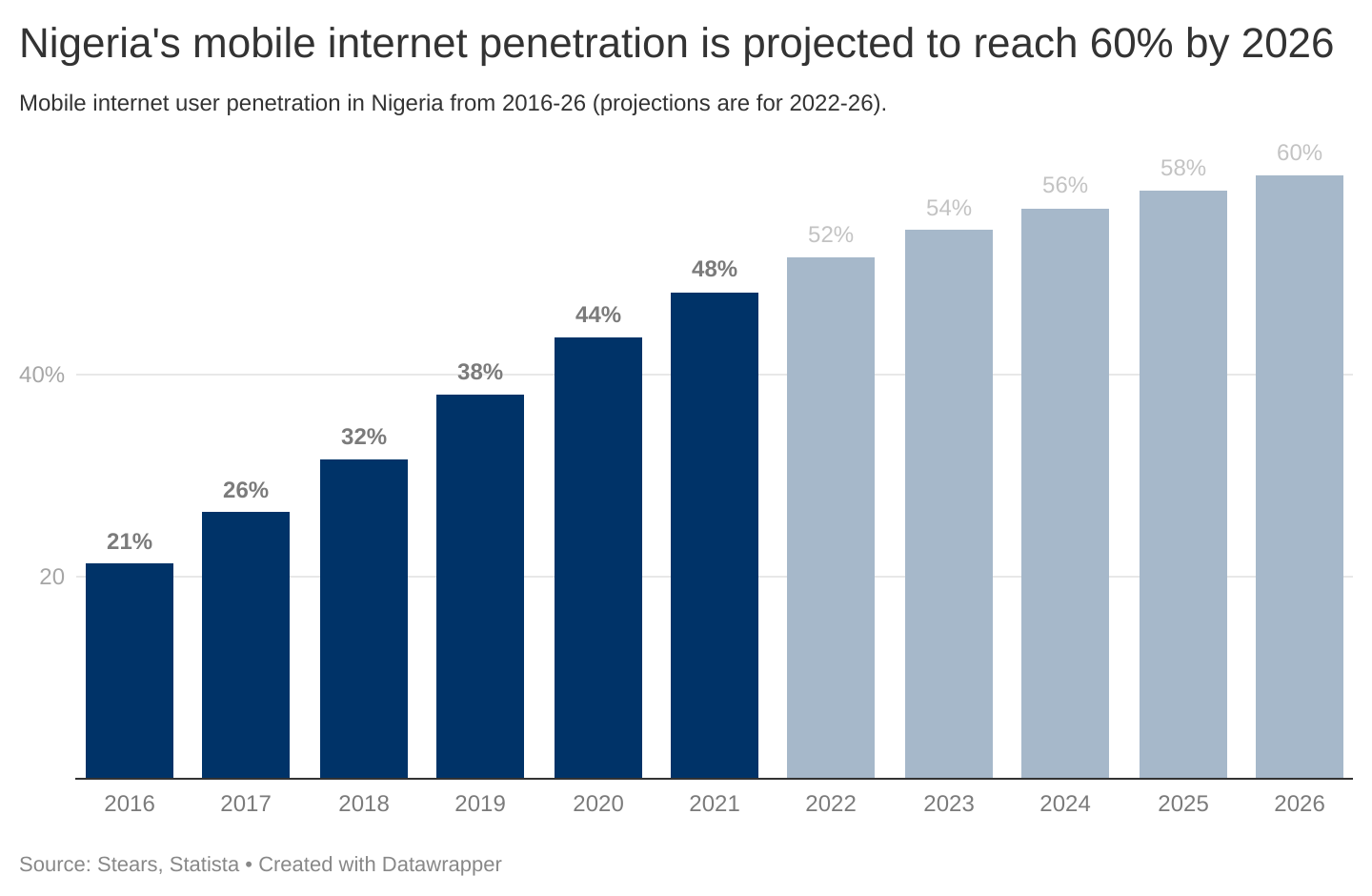

Currently, African economies lag behind the global average for broadband access and speeds. Still, the continent is projected to see improvements in its connectivity with investment being made in projects such as the Equiano Subsea Cable, which should, in turn, reduce the proportion of fixed broadband connections with download speeds of less than ten mbit/s (currently at 64%).

Through innovations in payments, healthcare, banking and much more, the digital economy is changing—and in some cases undermining—conventional notions about how businesses are structured, how they interact, and how consumers obtain services, information, and goods. In a recent report, the World Bank estimates that by 2025, the resulting impact of the internet economy could contribute nearly $180 billion to Africa’s economy.

Our Knowledge Editor, Tokunbo Afikuyomi (Jr.), summarised this shift from an economic perspective in an insightful article.

As he put it, the traditional model for the economy has been transformed from economic output being the result of combining the inputs of capital, labour and land—amplified by technology. Now, data and broadband can be seen as inputs in the production of output in an economy as they can be improved by technological advancements, the same way labour and land can.

Over the past decade, the growth in Africa’s internet gross domestic product (iGDP)—defined as the internet’s contribution to the GDP—has been strong.

Less than a decade ago, Africa’s internet economy was estimated at roughly 1.1%, or $30 billion, of its GDP. A recent analysis by Accenture found that iGDP contributed approximately $115 billion to Africa’s $2.55 trillion GDP (around 4.5%) in 2020, up 15% from 2019.

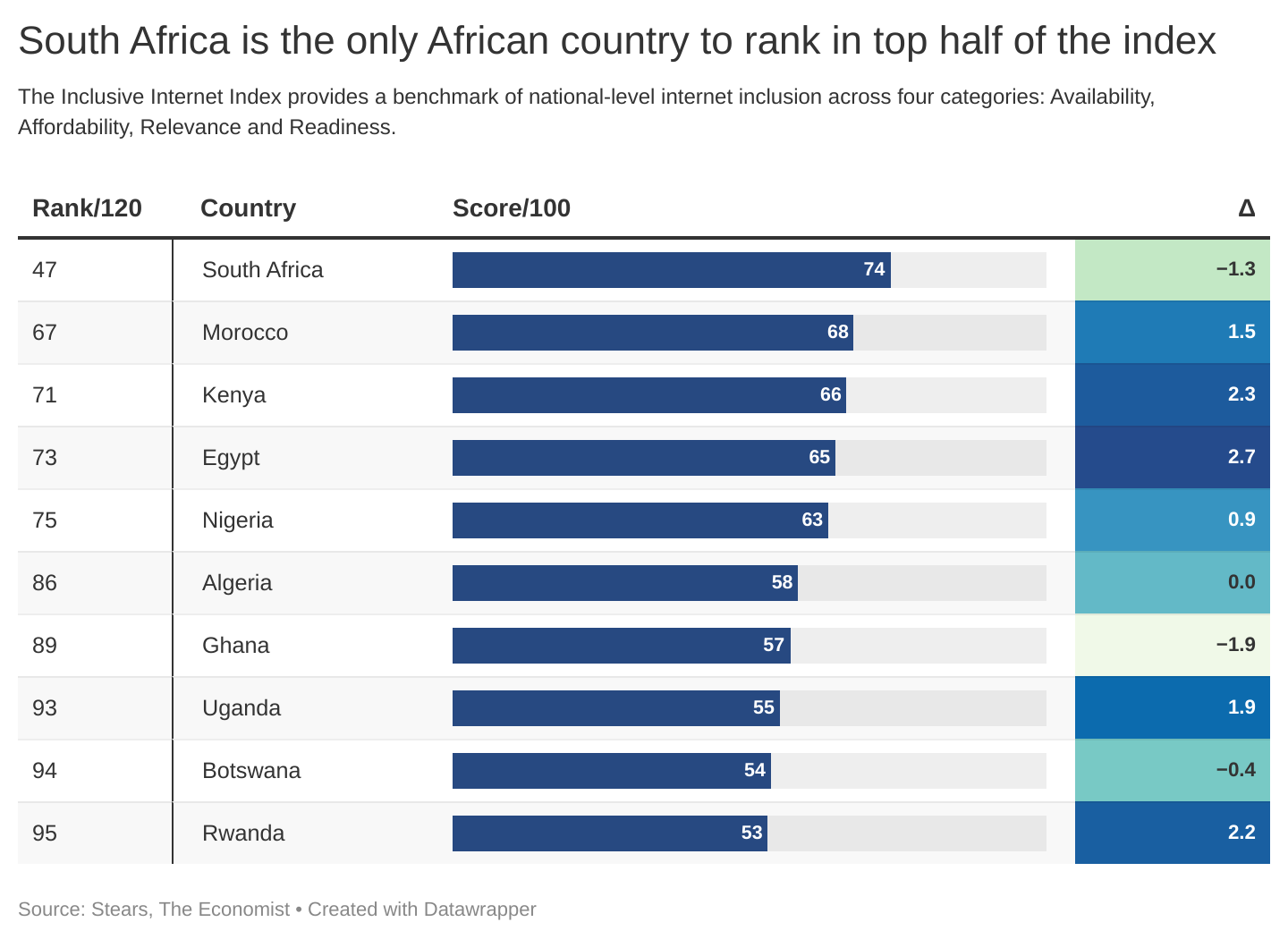

However, as improvements are being made, African countries still dominate the bottom percentile of the Economist’s Inclusive Internet Index, which ranks 120 countries based on their national-level internet inclusion.

But, this data still doesn’t capture the whole story.

Unfortunately, economic data can be misleading.

Last year, Nigerian mobile users between the ages of 16 to 64 spent almost 5 hours a day on the internet.

This captures digital platforms across social networks, navigation apps, messaging, calls, music, smartphone apps, etc. Like most smartphone users, I am lost without an internet connection. We rely on network connections for basic tasks such as listening to music, travelling, and communicating with coworkers and friends. Even my meditation time relies on a network connection to download the latest Calm or Headspace sessions.

But if we look at the economic data, you might question if the digital revolution has happened.

Granted, only about half of the Nigerian population has access to a mobile phone, and even fewer people have a reliable and affordable network connection. Nevertheless, the contribution of the information sector as a share of total GDP barely scratches the surface of the actual activity in the digital economy.

To borrow from the American economist Robert Solow, the digital age is everywhere except for productivity statistics. His original quote referred to the missing effects of the computer age in economic productivity data. This is known as the Solow Paradox, which was resolved by adding the technology, retail, and wholesale sectors to US productivity metrics.

The value of the digital economy is underrepresented in traditional economic statistics because this is based on what people pay for goods and services. But many consumers get immense value from free digital goods such as social platforms.

This is not a new problem.

Trying to measure things the right way is an age-old problem in economics. One challenge, for example, that all development economists battle to this day is how we measure “poverty”.

In the case of economic activity, the underlying problem faced is that economic metrics such as GDP capture the monetary value of goods produced by the economy. Effectively, it measures what we pay for and not the value derived from the goods or services. It is entirely possible for the value enjoyed from goods and services to go up while GDP goes down.

So it can be a misleading proxy when we attempt to use it to capture the activity and trends in the digital economy simply because it only tells us what people paid for and not how much value was created.

Is Airbnb a hotel booking or apartment letting service?

To help grasp this issue with misleading economic metrics and their effect on decision-making, let’s take the example of Airbnb.

In its early days, Airbnb struggled to explain its market to investors. Was it a hotel booking service competing with the likes of Expedia or a short-term apartment letting service competing with the rental agency market?

Well, the answer was neither.

The idea for Airbnb was born in 2007 out of a struggle between two friends to pay their rent, and they leveraged their only asset to overcome this problem, i.e. unutilised space in their apartment. Fast-forward a couple of years, and they scaled the concept to accommodate conference and convention attendees looking for accommodation solutions from locals with spare rooms or empty spaces when hotels in the area were sold out.

If Airbnb were classed as a hotel booking service, its market size would’ve been pegged to the number of hotels operating in a defined area. If it were classed as a short-term rental service, it would’ve been grouped with other agencies who rely on a property’s negotiated rental value, i.e. the real estate services market. While both of these are established sub-sectors, deciding to invest in Airbnb based on the economic statistics for these markets would’ve missed the point of Airbnb altogether.

The company played on the emergence of new business models made possible by the digital revolution.

There were many unused spaces and properties across cities undervalued by existing statistics because they did not account for the potential value that could be derived from those spaces. Instead, traditional activity measures in these industries relied only on the price paid for the asset or rental. But, with greater interconnectedness, a collaborative business model made peer-to-peer rentals possible as a better-defined category in the industry.

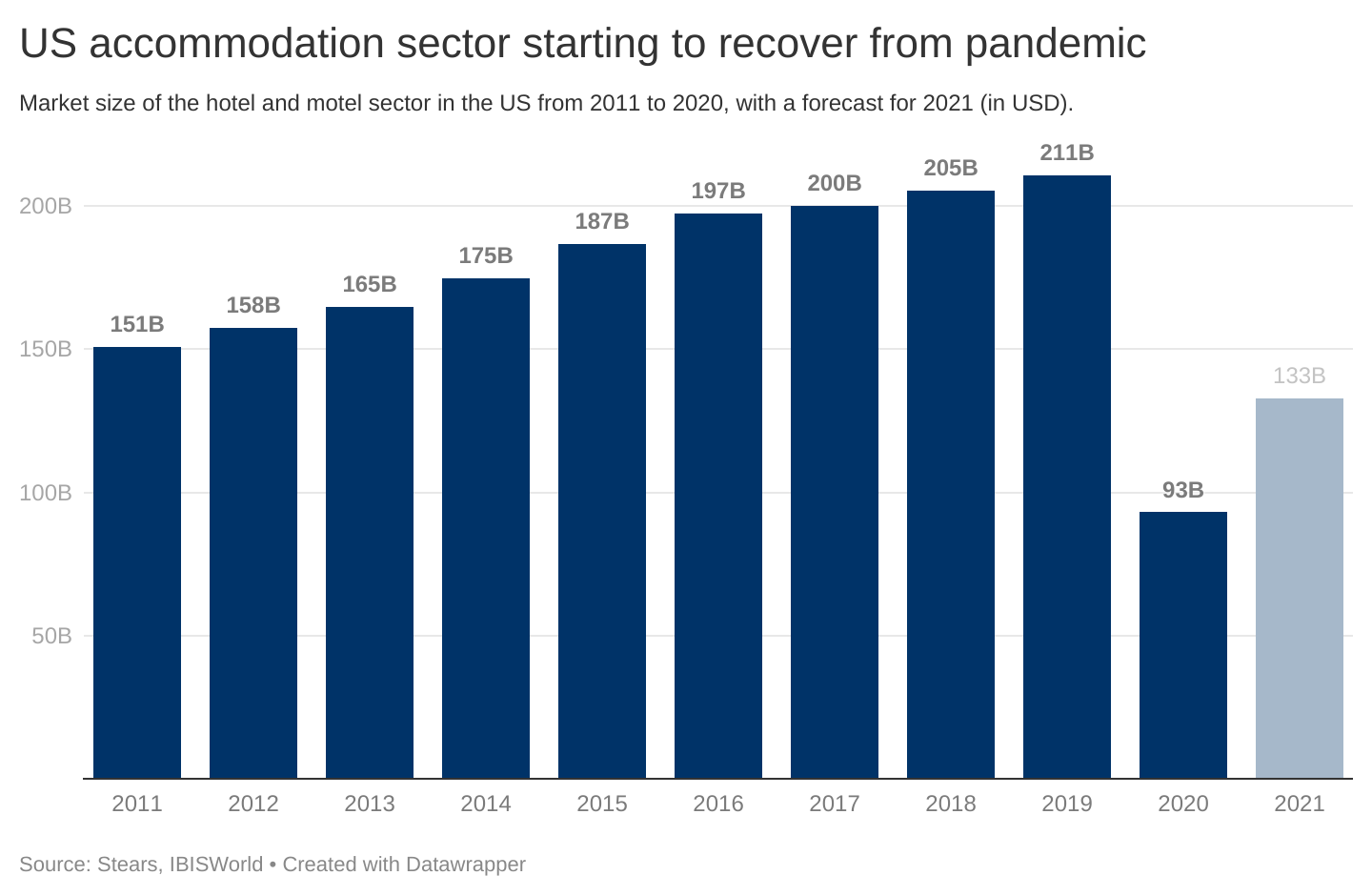

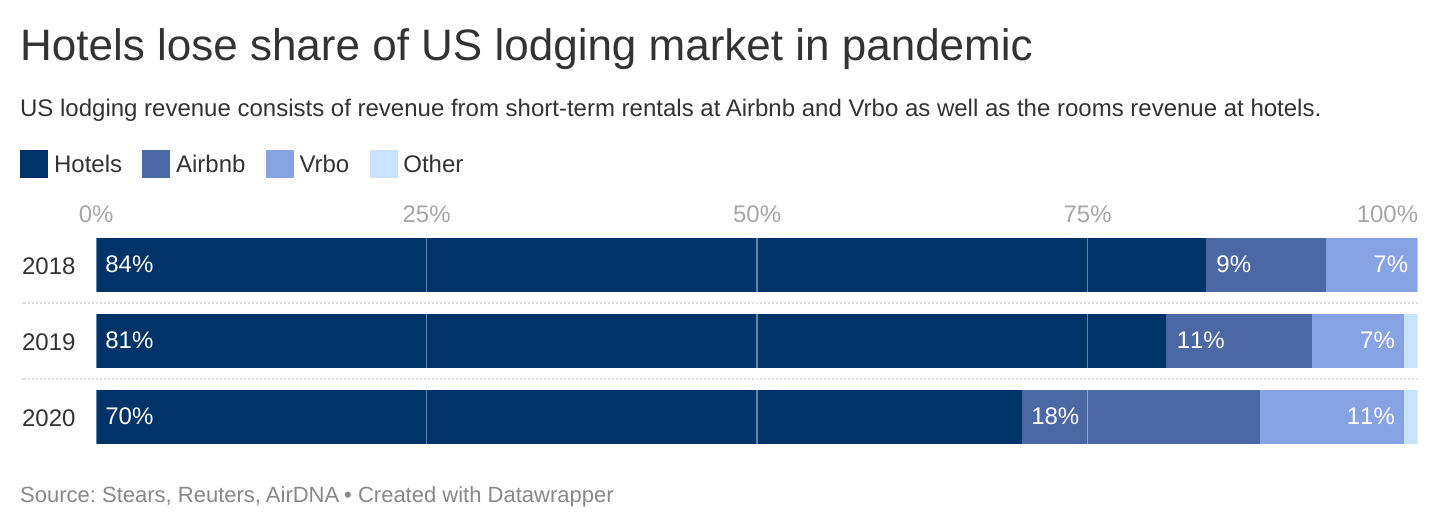

There are arguments on the cannibalisation effects Airbnb has had on the existing hospitality industry, but the impact so far has proved otherwise—excluding the shock of the pandemic.

The US Bureau of Labour Statistics reported in 2018 that Airbnb had a positive effect on both consumers and hosts. While hotel revenues may have been 1.5% higher if Airbnb did not exist, more than half of that amount would not have resulted in hotel bookings if Airbnb were not available. Particularly in larger cities, Airbnb increased overall room availability and better prices for consumers, especially during peak times.

While Airbnb’s market share in the overall lodging market has increased, this has been coupled with growth in the lodging market size. However, the pandemic shock resulted in a spike in Airbnb’s market share and a decline in market size. Industry experts suggest this may have been because of quarantine rules that made their accommodation's private and contained nature more appealing to travellers.

We’ve seen other case studies of successful collaborative business models built on the back of the digital economy where the category did not previously exist, e.g. Uber, TaskRabbit and Wise.

But, if traditional economic statistics for critical business and policy decisions can lead us astray, what alternatives are available?

How many economists does it take to measure value?

It’s a tricky question because while there are theoretically better measures for value created, they are hard to capture in practice.

In theory, consumer surplus (or benefit) could be a better measure of value created by goods and services to the consumer. This is the difference between the maximum price a consumer would be willing to pay for a good or service and the price they pay (the market price).

For instance, Shehu is willing to pay ₦3,000 for a single stick of suya. In Abuja, he spends around ₦1,500, but in Lagos, he begrudgingly pays ₦2,000.

Shehu’s benefit is different depending on where he buys his suya. In Abuja, the consumer surplus when you subtract the amount he’s willing to pay from what he pays is ₦1,500 (₦3,000 mimus ₦1,500). But in Lagos, it’s ₦1,000 (₦2,000 mimus ₦1,500), indicating that surplus varies depending on the seller, not just how much the buyer is willing to pay.

But enough about suya.

The vital point to take away here is that assessing the value created by a good or service simply by how much is paid can grossly underestimate the actual value to the consumer.

A good example is a comparison between a print encyclopaedia and Wikipedia. A few decades ago, people spent thousands of dollars on encyclopaedias, indicating its customers considered it worth at least that amount. Today, Wikipedia rivals encyclopaedia content in quantity and perhaps quality, but Wikipedia is free. As a market measured by consumer spending, print encyclopaedia “had”—as the industry is all but dead now—a bigger market than Wikipedia.

On the other hand, research has found that the median value that US consumers place on Wikipedia is around $150 a year, which translates into at least $42 billion in consumer surplus that isn’t captured by economic statistics—excluding the rest of the world.

Now apply this to various digital products consumed for free or near-free across Africa and imagine the scale of value missed by existing statistics.

Even more widespread products like Google’s search are undervalued because economic measures rely on advertising revenues to indicate the value of search to the consumer. Estimates from research conducted by economists on American and European consumers suggest that the value derived from products such as Google search and Facebook can be as high as three times the amount generated in advertising revenues.

There are known challenges to measuring consumer benefit.

While the theory of consumer benefit is great compared to consumer spending, it cannot be directly observed, so it’s a tricky measure to adopt practically. In most cases, surveys are used to gauge whether consumers would give up a good or service in return for financial incentives. Naturally, the survey design, sample group selected, and incentive choice can affect the results, making the measure less comprehensive and precise.

In addition, the reliance on surveys makes it hard to compare values across regions as survey parameters have to be adjusted to fit the targeted demographic, which means it is difficult to get a like-for-like comparison across countries or even states.

Consumer context also matters.

We can see the potential benefits of measuring the value created instead of the amount paid in assessing the digital economy. It provides a broader perspective on the potential for new markets and industries.

It also comes with caveats, and the imprecision may make some uncomfortable with the metrics.

Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out the power of this approach as a mental model for assessing opportunities and risks in markets enabled by the digital economy. This approach, though imprecise, can still provide a comparable view on the impact of digitalisation on existing markets and the potential for new markets to be created.

By not accurately valuing a growing part of the economy, decisions made, especially by governments, can easily undermine the potential of the digital economy. After all, the internet economy cannot improve its productivity and efficiency across large swaths of the economy if we can’t accurately identify where to find the best return on investment.