Over 2.5 billion people worldwide do not have access to clean cooking facilities.

Instead, they have to rely on biomass like firewood, kerosene or coal. This is concerning because these are fuels with high carbon dioxide emissions and household air pollution, caused mainly by cooking smoke, which leads to around 2.5 million global premature deaths every year.

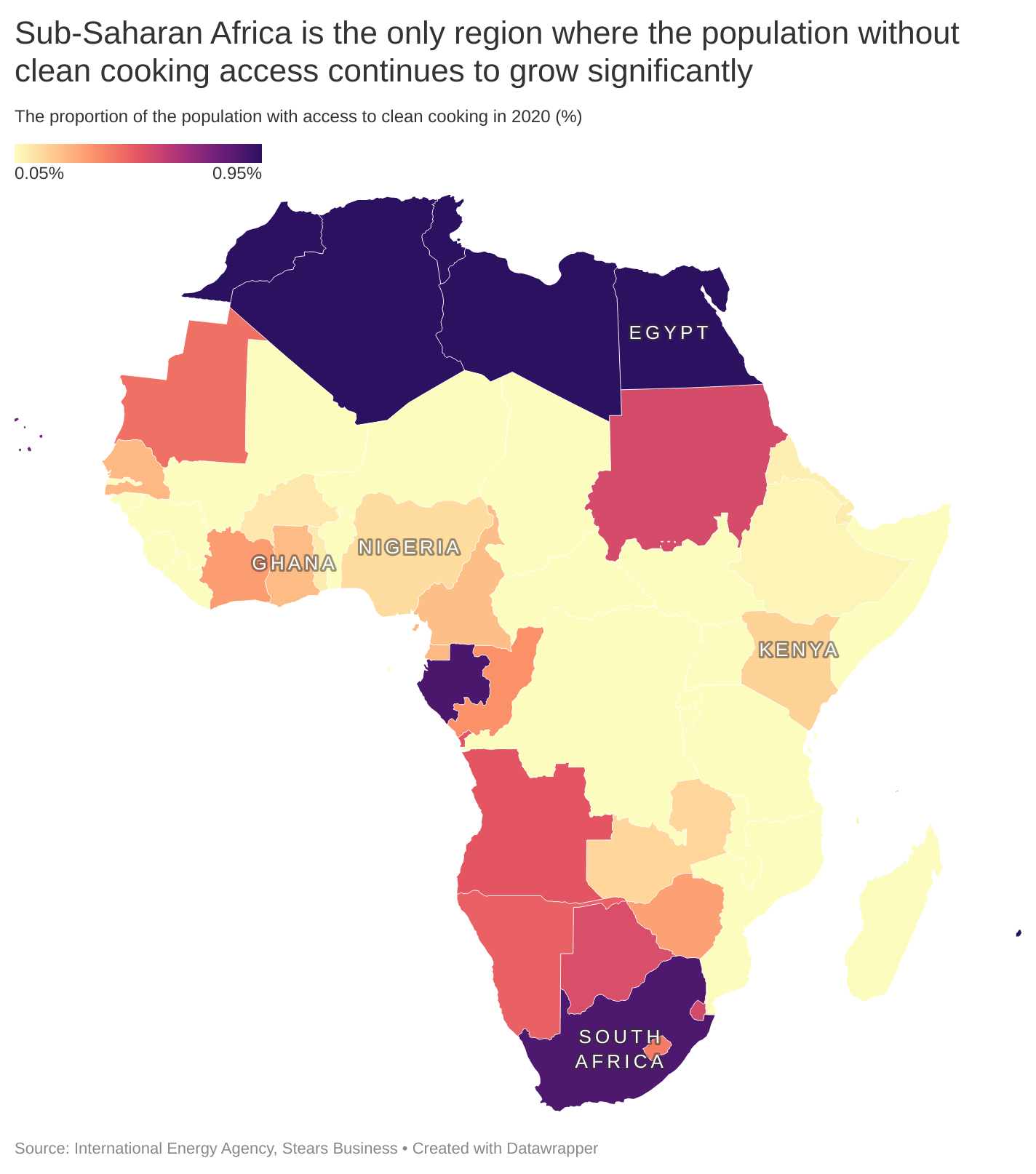

The figures are even worse in Sub-saharan Africa (SSA). Although Asia accounts for 60% of the global population without access to clean cooking fuels, much higher than SSA’s 38%, SSA is the only region where the number of people without clean cooking fuel continues to rise significantly.

Key takeaways:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region where the number of people without access to clean cooking fuel continues to rise significantly. This is because our population is growing faster than clean energy supply.

- Liquified petroleum gas or cooking gas is the most available clean cooking fuel

This is primarily because the SSA population is growing faster than the supply of clean cooking fuels. On the one hand, the proportion of the population with access to clean cooking fuels increased from 15% to 17% between 2019 and 2020. But on the other, thanks to population growth, the actual number of people without access rose to 940 million in 2020—a 10% increase from 2019. Essentially, a relative comparison showed improvement, but in absolute terms, more people were without clean cooking access in 2020 than in 2019. And this has a significant impact on our health. Close to 490,000 people die prematurely every year due to household air pollution and unsurprisingly, women and children are the most affected given that they spend more time doing household activities.

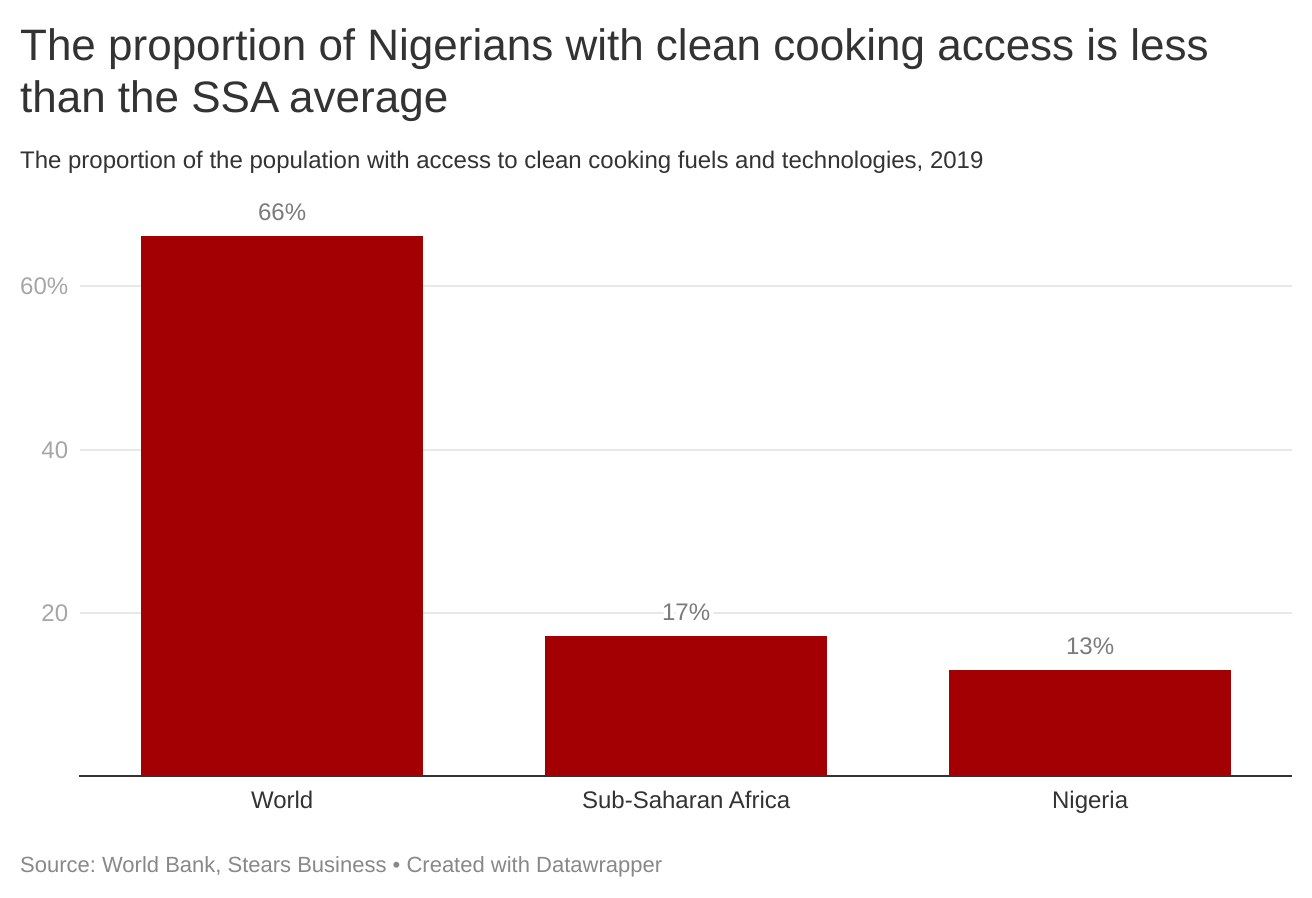

But, again, Nigeria’s case is even worse. Only 13% of Nigerians have access to clean cooking fuels, less than SSA’s 17% average. In comparison, about 23% of Ghanaians and over 86% of South Africans have clean cooking access.

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) forecast scenario which takes into account current and announced policies across the world, by 2030, there will still be 2.1 billion people worldwide without access to clean cooking fuels. But, by 2030, this population will be almost equally split between Africa and Asia. This is because, according to the policies in SSA, the rate of increase in the access to clean cooking fuels will not exceed population growth. As a result, the number of premature deaths due to household pollution and smoke inhalation will continue to increase.

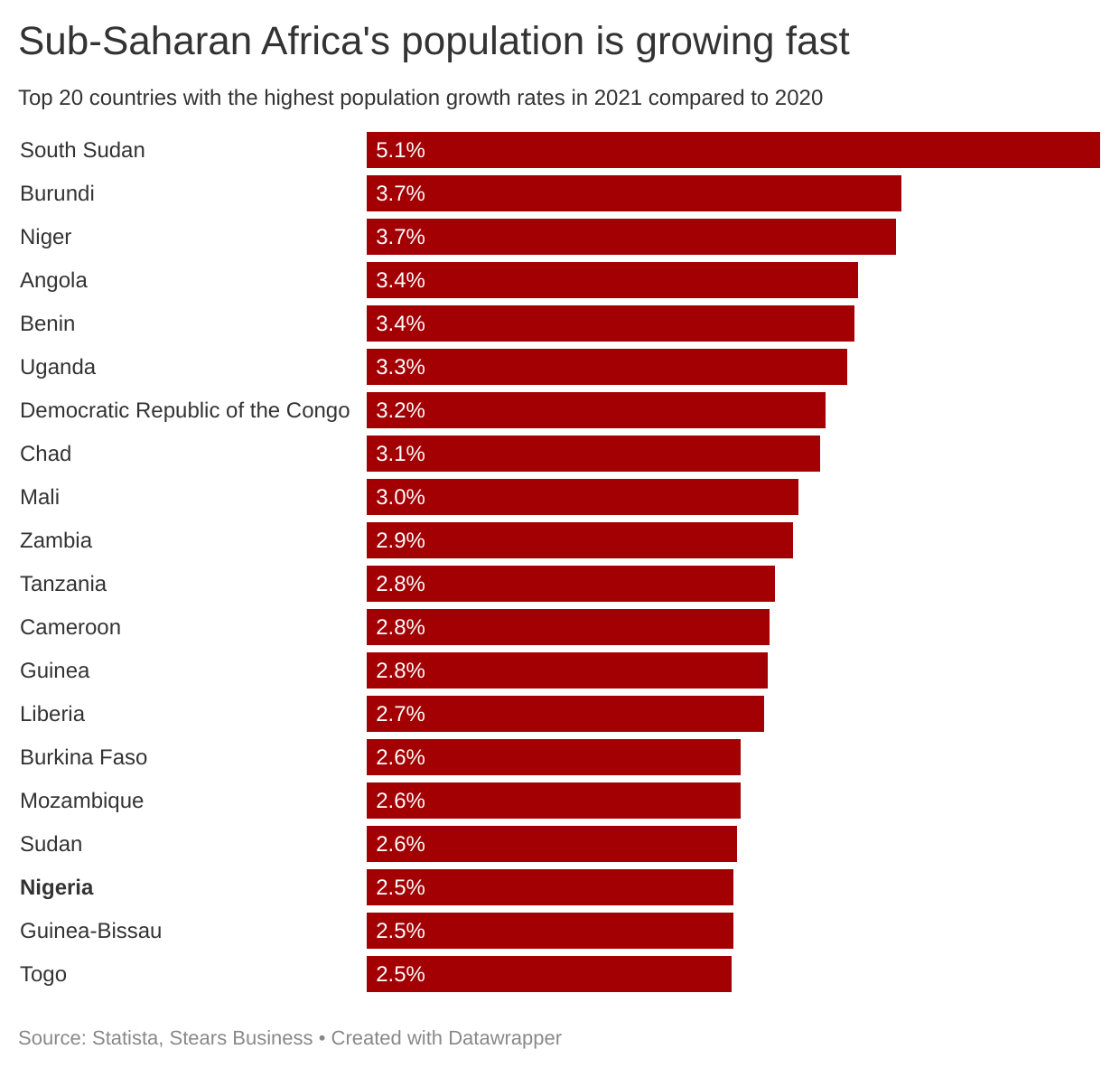

The way I see it, there are two issues. The first one is that a significant proportion of the current living population today does not have clean cooking access and this number continues to grow mainly due to economic factors such as poverty and high prices, and even non-economic factors such as lack of education. Then the second issue is that the supply of clean cooking fuels is struggling to keep up with our population growth. For instance, the top 20 countries globally with the fastest growing populations in 2021 are in Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa especially, with Nigeria at the 18th spot.

While we definitely have a big problem with population growth, our most significant issue is still access to clean cooking fuels. Our high population growth isn’t a problem by itself. As Fadekemi, our Editor-in-Chief wrote in this story; the problem is our lack of progressive economic policies. And this lack of progressive economic policies is why a significant proportion of our population lack access to clean cooking fuels.

But, before we dive into what our current policies are or what they should be, what are clean cooking fuels? And what clean cooking fuels are available to Nigerians?

What are clean cooking fuels?

Let’s take it back to the basics of what makes a fuel clean.

The term “clean” is relative. An absolutely clean fuel would be one whose production and use have zero emissions. But, in reality, hardly any fuel is absolutely clean. And, until technology evolves to the point where clean energy sources are affordable and readily available, we have to settle for relative cleanliness. For instance, natural gas is the fuel of choice right now because it is relatively the cleanest fossil fuel, and its relative cleanliness as compared to coal and crude oil.

This same concept applies to cooking fuels.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 7 aims to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”. Sustainability is super important, and it means intergenerational equity. We shouldn’t make the next generation or the next person worse off while fulfilling our energy needs. This is where firewood and kerosene fall short. Supplying firewood causes deforestation, and the extraction of kerosene from crude oil causes environmental pollution. Also, we’ve already seen firewood and kerosene hurt people's health, especially women and children.

The WHO, UNDP and the IEA identify clean cooking fuels as Liquified petroleum gas (LPG), electricity, ethanol, biogas, natural gas and solar.

But different regions have different definitions of what is affordable or reliable. Sustainability and modernity are more universal. For instance, electricity wouldn’t be a reliable cooking fuel for Nigerians when over 40% of our population does not have electricity access from the national grid. Another way of looking at reliability is availability, and this also cancels out ethanol, biogas, and even natural gas for cooking. We don’t supply these fuels at a large scale for cooking purposes yet. And solar for cooking is still a relatively new concept that Nigerians are still getting used to.

This leaves liquified petroleum gas (LPG), what we call cooking gas, as Nigeria’s closest and most popular option. It’s reliable, sustainable and modern. Affordability is a sticky issue, but we’ll get to that. First, we need to understand what LPG is.

Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG)

I’ve always hated chemistry, so I won’t bore myself or you with the chemical details. Instead, here are some essential facts you should know.

LPG comprises two flammable, non-toxic gases called propane and butane. It’s also odourless, but an odorant is added during production so people can detect leaks. It can either be derived from natural gas or crude oil, but approximately 60% of the world’s LPG production is from natural gas.

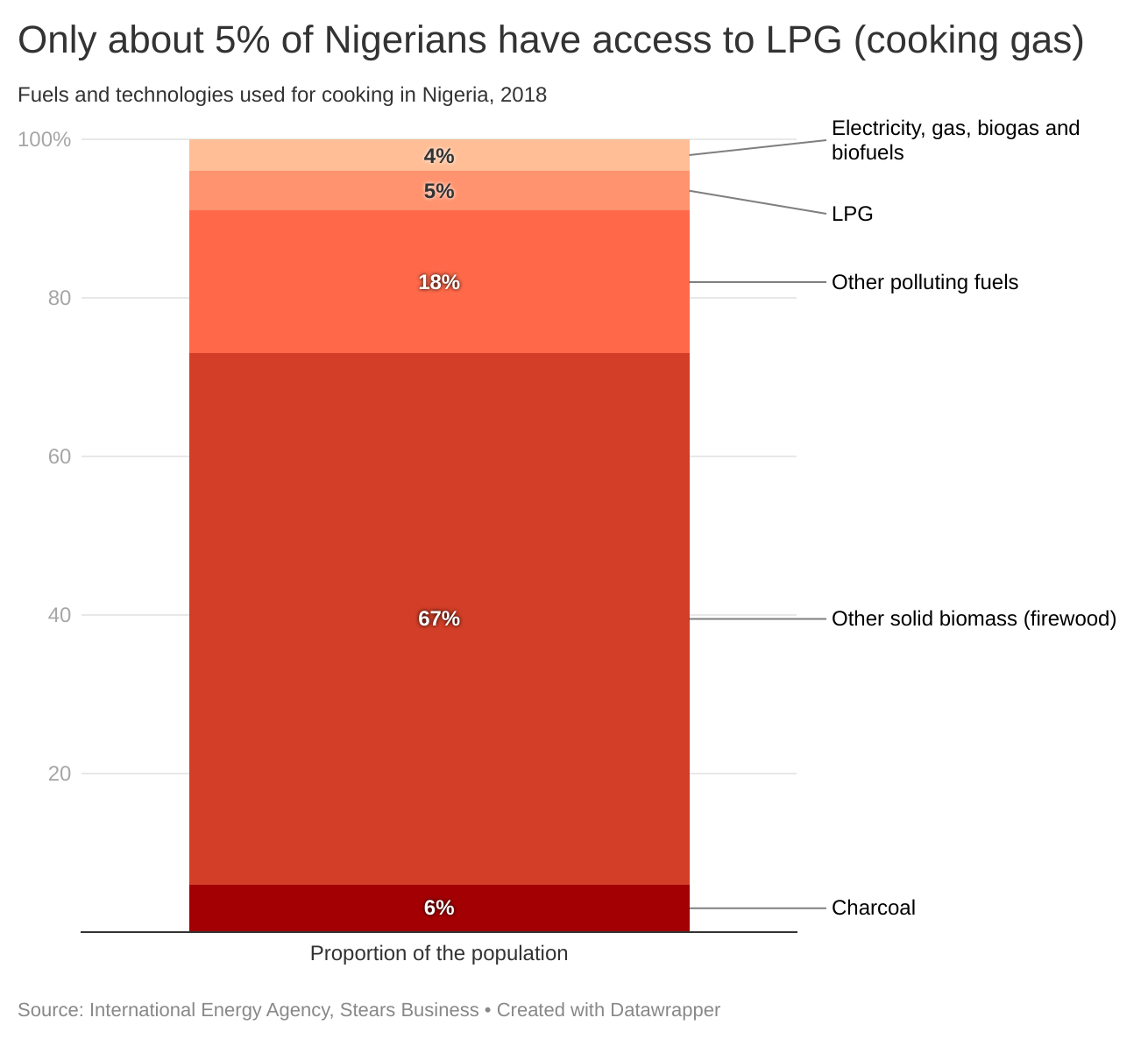

In Nigeria, as of 2018, 5% of the population had access to LPG for cooking. It’s our most widely used clean cooking fuel, especially in urban areas, though 5% seems small. But, this just shows how poor access to clean cooking is.

According to the president of Nigeria’s LPG Association, as of December 2020, Nigeria’s LPG demand was 1 million metric tonnes annually. In comparison, Ghana’s consumption in 2020 was less than 350,000 metric tonnes. Our vast population means that just 5% of our total population, our clean cooking fuel population, is about 10 million people. While at 26%, Ghana is less than 8 million people. However, no thanks to this large population, we have a long way to go to increase clean cooking access.

In terms of supply, most of our domestic production is from Nigeria LNG Limited (NLNG). NLNG, a joint venture owned by the NNPC, Shell, Eni and TotalEnergies, produces around 7 million metric tonnes (mt) of LPG per year. However, it only supplies about 450,000 mt domestically (about 6% of its production) and exports the rest. Before 2021 last year, NLNG only supplied 250,000 mt domestically (about 4% of its production). The rest of our LPG was imported. But when international natural gas prices started rising in 2021 and LPG prices also increased, the NLNG had to increase supplies to 450,000 mt.

According to the National gas policy, even the NLNG’s 250,000 mt was underutilised because of illegal LPG importation. Essentially, undeclared imports are brought into Nigeria through Niger or Benin republic and also, some domestic production is undeclared and diverted.

This meant an excess supply of imported LPG compared to NLNG’s LPG. The likely cause is that the NLNG’s LPG production is limited, currently making up less than 50% of LPG demand. And its supply was stored, distributed and, to an extent, even marketed by an arm of the NNPC called the Nigeria Petroleum Marketing Company. So, private marketers had to import LPG to fill their storage facilities and supply to customers. But, only one company called Hyson, a joint venture between NNPC and a trading company, VITOL, imports LPG because there’s only one port with functioning import jetties in the country (Apapa). Hence, it was inevitable that smuggling would happen.

As we’ve seen in the petrol market, government market controls lead to smuggling. The difference is that the government control here isn’t on price, as LPG is fully deregulated and is the only VAT-inclusive petroleum product. Here, the government controls are on supply due to importation infrastructure issues.

The government declared the 2021 decade as the decade of gas, and the 2017 national gas policy sets out the steps to increase gas consumption, including cooking gas. Let’s see how the policy intends to fix Nigeria’s cooking gas problem.

The National gas policy

According to the policy document, Nigeria’s LPG market suffers from an inefficient distribution chain and higher prices than if the market were efficient. It identifies critical infrastructure gaps: jetties, depot storage, road transport, distribution terminals and cylinders. Basically, everything after production is a problem.

The jetty problem is the Apapa port problem which we covered earlier. The depot storage issue is another problem. According to the policy document approved in 2017, we have 14,500 tonnes of private storage and 4,000 tonnes of government-owned storage only at Apapa and Calabar. For context, our annual demand is 1 million mt, approximately 83,000 mt per year. Next, road transport from the depots in Apapa and Calabar to distribution terminals across the country is a big problem. The document states that there are around 900 barely functioning old trucks that can transport only 2,000 tonnes. For distribution terminals, we only have 200 across the country. Finally, gas cylinders are identified as the most critical infrastructure problem, alongside import jetties. We have 1.8 million gas cylinders across Nigeria, but only about 10% are safe for use as most consumers’ cylinders are hazardous.

In terms of solutions, the policy identifies the need for investments in infrastructure, leveraging distribution chains from other industries such as bottling and beverage, and educating Nigerians on the upsides to gas use. It also states that the government should remove VAT on gas and stimulate local cylinder production.

It’s not hard to see where the policy falls flat. It doesn’t precisely state how or when these solutions will be implemented, nor does it note how much investment will be needed especially given that the problems are capital-intensive infrastructure issues. This isn’t surprising given that this is the general structure of Nigeria’s policies across sectors. Just read our review of the National development plan—our policies are descriptions of our problems with solutions presented as bullet points without any clear roadmap.

So what should Nigeria’s gas policy look like?

The ideal policy

Our ideal gas policy should have started with a roadmap that shows the government’s vision for LPG use in Nigeria. Our LPG roadmap should show our capacity to increase LPG use over time by showing potential supply lines for importation and production as we invest specific amounts of money to address our issues.

Speaking of addressing issues, a good LPG policy should state precisely how the government intends to address our issues. The policy fails to address one of the two most significant issues, the importation problem, and it vaguely addresses the second, which is pricing.

Nigeria’s importation infrastructure issues are well-known, and we’ve written articles on why we need to decongest our ports. For pricing, affordability is a big problem with cooking gas. Between December 2020 and December 2021, the average cooking gas price for a 12.5 kg cylinder rose from about ₦4,000 to over ₦7,000, thanks to volatile global gas prices. But, even besides this, there are upfront capital costs involved with cooking gas, and consumers must buy gas cookers and gas cylinders.

According to the World LPG Association, a good policy document must include financial incentives because this is one of the biggest blockers to consumer demand. Besides giving people cash, one way to increase LPG use, especially in rural and low-income areas, is by installing LPG equipment for consumers. In 2007, Indonesia gave 58 million kerosene users free 3kg cooking gas cylinders with hoses and hotplates for cooking, and this policy successfully converted 58 million kerosene users to gas users.

More Nigerians must gain access to clean cooking fuels because increased clean cooking fuels could mean the difference between life and death, especially for women and girls.