In 2012 Paul Graham, the founder of the prestigious startup accelerator and venture capital firm Y Combinator equated being a startup founder to being an “economic research scientist”. In his words, “you don't know for sure which problems are soluble; but you're committing to try to discover something no one knew before”. Think of the previously crazy-sounding ideas that are now businesses, like sleeping in a stranger’s house while on vacation instead of a hotel (Airbnb) or building a massive taxi company without owning any taxis or hiring any drivers as employees (Uber).

When a founder discovers this solution, they call it a startup.

Key takeaways:

-

Startups are designed to build products for a large market that are high-impact and hyper-growth. To get off the ground or grow as fast as they should, they turn to funding from investors.

- Due to the high failure rates of startups, investors are always on the

Startups are designed for high growth and disproportionately high impact. They are designed to solve problems for large markets. To get started or grow fast, they turn to funding. Even when a startup is growing, it typically raises more funding to grow even faster. Funding puts the startup in a position to choose its growth rate.

Funding enables startups to get off the ground, make A-team hires, build their growth machine and experiment with products. With funding, startups can do whatever it takes to find growth.

But startups are risky.

Forbes estimates that 90% of startups fail. The strikeout ratios, that is, the proportion of companies that fail relative to those that succeed, are driven by the 80/20 rule. VCs model their portfolios on the assumption that most of their companies will give <1x returns. Globally, even for the best-performing funds, it's been observed that 90% of returns come from less than 20% of investments. In many portfolio construction models for VCs, only 2% of investments can return at least 20x of the investments - the big wins.

With such high odds of failure, investors become rigid. They are selective with their capital deployment and need to be smart (but also lucky). Particularly in the early stages, they do their very best to invest in founders who can work closely with them and have the highest chances of success. The startup ecosystem sometimes calls this “founder-fit”, ‘founder-market fit” or even “founder-investor fit”. Regardless of the description, our observation is that the search for “fit” introduces inequalities and biases into fundraising outcomes.

For instance, research has suggested that startups founded or co-founded by women generate more cumulative revenue and provide stronger financial returns per dollar invested than male-founded startups. But startups founded or co-founded by women still got just 2.2% of all funding globally in the first half of 2021, which is strange for an industry built almost entirely on returns. In reality, thanks to the dominance of white males in VC, other men are more likely to be selected as the right “fit” for most investors.

However, today’s analysis is not focused on gender biases. Today, we shall focus on another signal that investors use to determine the investability of a founder; their educational background.

We will explore the inequality in funding outcomes between foreign-educated CEOs and locally-educated CEOs in Africa. And we will explore how social capital & biases enable this gap.

Per The Big Deal dataset, African startups broke various records in terms of funding in 2021. For the first time, startups managed to raise over $4bn. Nigeria became the first country to raise at least $1bn in a single year while fintechs brought in $1.8bn; another first. For all the years in which Africa has been heralded as the last frontier of tech and innovation, 2021 proved that investors were willing to back this with their money.

This funding was raised by 818 CEOs, with 232 of these leading Nigerian startups (startups with Nigeria as their headquarters). The CEOs can be grouped into three categories: We can call the first group the foreign-educated CEOs—those that went to school in North America, Asia, or Europe and could either be Africans or expatriates. In the second group, we have locally educated CEOs who attended Nigerian universities, and finally, we have CEOs who attended universities in other African countries.

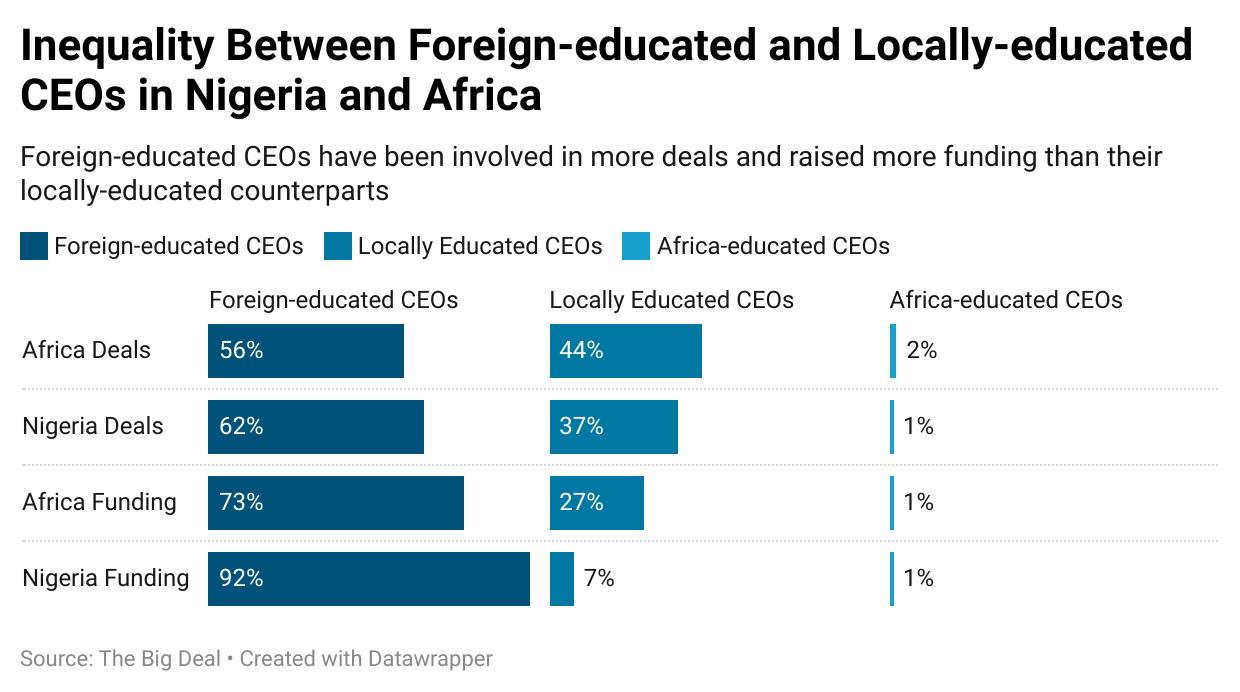

Across the entire continent, the foreign-educated CEOs accounted for 56% of all deals that involved African startups. The locally educated CEOs raised 44% while those educated in another African country raised just 2%.

In Nigeria alone, the disparity was even bigger. Foreign educated CEOs accounted for 62% of all deals compared to 37% of the locally educated CEOs. The inequality is stark when it comes to actual funding amounts. Foreign-educated CEOs raised 73% of all the money that African startups attracted. In Nigeria, this figure was 92%. Here’s a look at the data for yourself:

Why do universities matter in the startup ecosystem?

To understand the importance of universities and startup ecosystems, let's take a trip to North America and look at the synergies between Stanford University and Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley is widely regarded as the global headquarters of technology and innovation.

The nucleus of Silicon Valley is Stanford University.

Founded in 1885, Stanford University was once considered a small engineering school behind the Ivy League universities. Today, its alumni have led the innovation culture across the world.

We can trace this trend back to an engineer, Fred Terman, who had made a name in military research during the Second World War. He pushed for the university to build an industrial park that would act as the first networking hub for people in tech, academia, and industry.

Companies could lease land in this park and build products. The first successful companies to call this industrial park home were the likes of Lockheed, Fairchild, Xerox, and General Electric. As the park grew, so did venture capital firms, angel investors, and innovators around it. Currently, the Industrial Park houses companies like Tesla and Skype, and it is also home to multiple tech law firms and R&D labs.

Stanford University stepped out of just teaching and also built an environment where its students could transfer their innovations from the class to the market. Arguably, it worked. It is home to many of the world’s largest hi-tech corporations, including 30 companies that made it to the Fortune 1000. Global technology powerhouses like Google, Apple, Tesla, Netflix, Adobe, and Hewlett Packard (HP) among others, are all headquartered in the Valley.

Stanford alumni also have a culture of giving back to keep this loop going.

In 2013, it became the first university to receive $1bn in donations to its endowment fund. It also has programs like Stanford Alumni Mentoring where successful alumni take on Stanford students as interns. This has helped many students secure internship placements at companies like Palantir and LinkedIn under the tutelage of the likes of Peter Thiel and Reid Hoffman, some of Silicon Valley’s most well-respected entrepreneurs.

The university also runs startup competitions like BASE 150K and E-Challenge as well as classes like Launchpad and Creating a Startup which give aspiring entrepreneurs opportunities to meet and build on their ideas. Fellowship programs like Mayfield Fellows Program (Instagram founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger are alums), StartX and Lightspeed Ventures Summer Fellowship Program are all available to graduate and undergraduate students at the university.

Such deliberate efforts by the university have borne fruit. According to Pitchbook data, Stanford produced 1,127 company founders between 2006 and 2017. These founders launched at least 957 companies.

By 2020, 465 Stanford alumni were starting companies, more than Massachusetts Institute of Technology (367), Harvard University (293), UC Berkeley (277), and Cornell (143). In 2019, Stanford alumni were founders of 63 unicorns out of the 300 recorded that year.

Germany, Chile, and Canada have sent senior government officials to Stanford to learn how to nurture a startup environment and build a pipeline of startup founders from the university into the market. The data points to staggering success as far as high-growth entrepreneurship built on University culture is concerned.

Across the pond, Ana Bakshi, the director of the Oxford Foundry, an entrepreneurship centre at Oxford University, openly acknowledged how universities are “great places to accelerate new ventures.”

Now that we understand how much impact a single community like a University has, let’s take a look at how Universities affect African founders.

What universities did foreign-educated CEOs in Nigeria attend?

Most of the foreign-educated CEOs in the database we looked at haven’t just attended any universities in North America and Europe, they attended some top universities. Of the 136 CEOs whose startups raised funding in 2021 and are foreign-educated, 55 attended universities ranked in the top 1% globally according to the QS World University Rankings.

Of these universities, Harvard is the most popular destination with 7 CEOs. Imperial College of London is second with 5 CEOs. University of Waterloo and Yale are tied in third with 4 CEOs each. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Oxford, Stanford, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill all have 3 CEOs.

These 55 foreign-educated CEOs raised $414m last year, which accounts for 28% of the amount raised by the foreign-educated CEOs in Nigeria. Here, it should be noted that the foreign-educated CEOs raised a total of $1.463bn. $553m (38%) of this amount was raised by CEOs whose alma mater was confidential including the deals by Opay ($400m) and Trade Depot ($110m).

Looking at this trend, one key dynamic at play here is social capital.

Social capital is a fascinating concept that emerged from a French sociologist called Pierre Boudreau, who argued that there are many different forms of capital like human capital and financial capital. According to Pierre, these forms of capital are fungible, i.e. can be converted from one form of capital into another form of capital.

Social capital is an individual's network and the opportunities that can be derived from networks that a founder is embedded in. If those networks are large, respected, or prestigious, then a founder will have more capital access than someone without those networks. Social capital is also a signal to the market, as prominent ambassadors or advisors connected to a founder or startup attract even more supporters—like the Matthew effect. Often, social capital translates into financial capital.

To fundraise successfully, startup founders must build a strong network of professional investors and angels, advisors, entrepreneurs, and even other stakeholders like regulators. These are people that can help with funding or referrals. Social capital, or “who brought me the deal”, matters to investors.

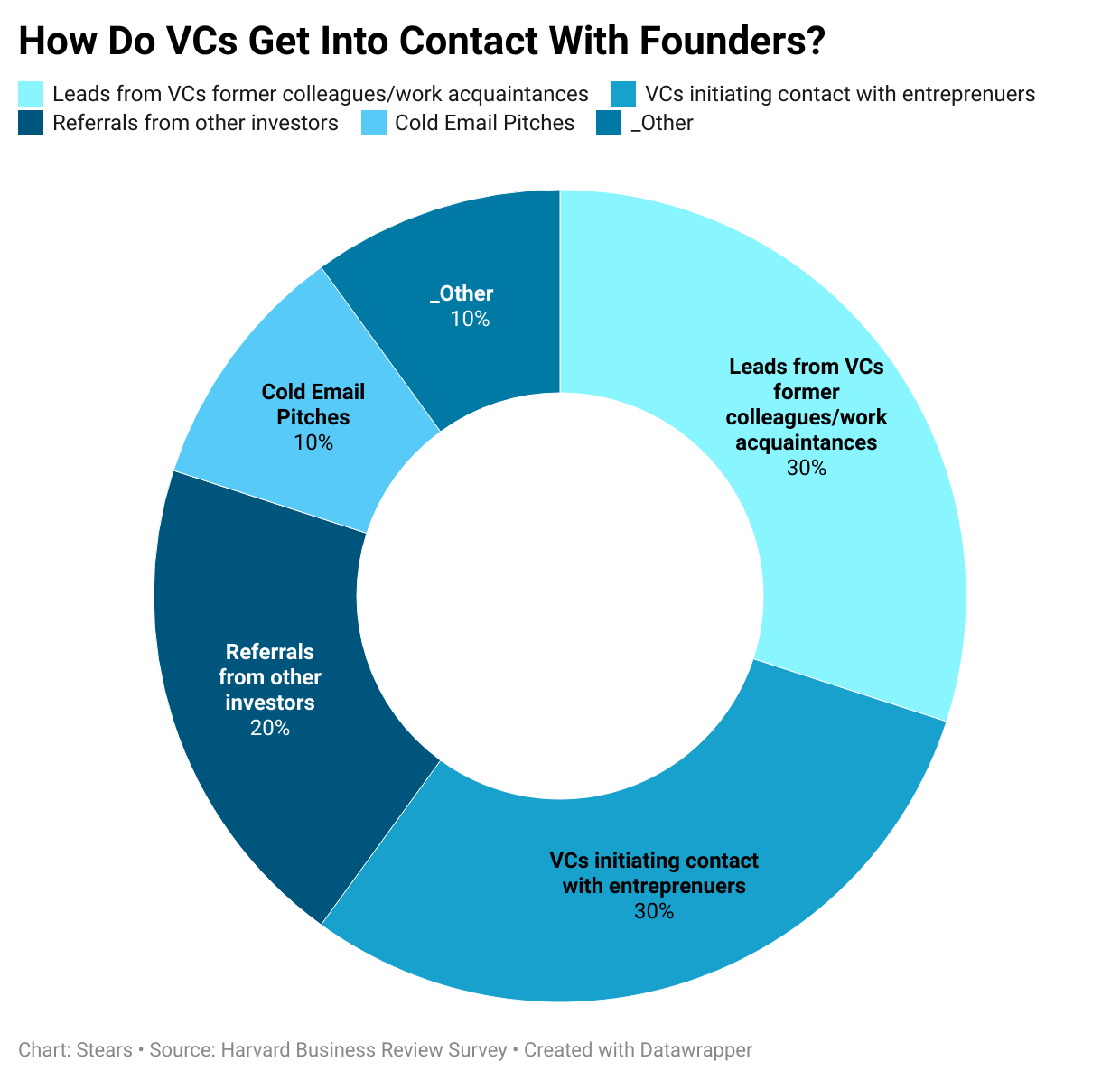

In a survey by the Harvard Business Review of 900 investors about how Venture Capitalists make decisions, data showed 30% of deals came from leads by former colleagues/work acquaintances, 20% from referrals by other investors, 8% from referrals by existing portfolio companies, and 30% through investors initiating contact with the founders. Only 10% of deals came through cold email pitches by founders. This points to VC being a relationship business where who you know can affect the kind of funding you receive.

Bringing it back to reality, the question to consider is “how do founders sitting in Kampala, Accra, and Lagos, who may even struggle to get international visas, get access to introductions to potential investors, if not through their extended social networks?”

With this establishment of the importance of social capital, we can start to see how your immediate network can limit your access to global capital from the most well-funded fund managers in the world. After all, who is more likely to have access to global social capital; the locally-educated CEOs or the foreign-educated CEOs?”

Let’s look at the data again to contextualise this.

The majority of African-headquartered venture capital firms invest in small funding rounds. According to the Big Deal Data, 7 of the 10 most active investors in 2021 were located in an African country. These were Launch Africa Ventures, LoftyInc Capital Management, Flat6Labs, Kepple Africa Ventures, Future Africa, 4Dx Ventures, and Norrsken. Between them, they participated in 220 deals and all of them were either pre-seed or seed rounds.

But, if an African entrepreneur wants to raise bigger financing rounds, they will have to go to the USA or Europe—that’s where the money is. The USA (280) had more investors that participated in any round in Africa than the runners-up, Nigeria (61) and South Africa (61) combined. The UK was fourth with 59 investors. The USA and the UK accounted for 58% of all investors that invested in African startups last year.

Arguably, foreign-educated CEOs likely have more access to stronger social capital than the locally-educated CEOs. They can turn to their alumni, professors, and contacts from events they attended while studying. In some cases, funding mandates linked to universities (i.e. where the university partners with a fund to invest in its alumni) may even restrict who can receive funds. Then there are the informal networks from “bike rides” and “coffee meet-ups”.

As if that's not enough, foreign-educated founders are more likely to benefit from similarity bias, which is the tendency for people to connect better with others who share similar interests, experiences, and backgrounds. These foreign-educated founders end up reflecting the biases of their funders.

In this study about similarity bias, two dimensions influence investor decisions; education and work experience. Founders that have gone to the same school, worked at similar companies or shared a similar experience as the investor, benefit from the bias.

Another bias that doesn't work in favour of the locally-educated founders is local. This refers to the geographic distance between an investor and their investment. Research that tracked venture capital investments in the US from 1980 to 2009 showed that nearly 50 per cent of investments were located within 233 miles of the VCs.

This can be seen when it comes to the current African unicorns. According to WeeTracker, Africa has 10 unicorns. Six of them; Chipper Cash, Andela, Wave, Flutterwave, Go1, and SWVL are all headquartered outside the African continent with the first four calling the US their headquarters.

In the end, social capital compounds as more and more founders win out.

The Odds Are Stacked Against Locally-educated CEOs

When it comes to social capital, locally-educated CEOs are playing catch up to the foreign-educated CEOs.

Is it changing? Of course. Outstanding businesses are being built far from the Silicon Valley base, and market makers like Y Combinator are leading the way.

But, a huge shift (primarily on the supply side i.e. VCs) is still needed to counter the bias against African founders. Some biases are deeply rooted in funding networks and will take time to counter.

When the opportunity is evenly distributed, it is easier for local founders to explore, make mistakes, take risks and understand the funding game too.

Perhaps if we pay more attention to it, locally educated CEOs will raise even more capital.