There are not many issues on which you would find many Nigerians in agreement.

There are even fewer that electoral candidates know they can always use to score cheap political points.

Key takeaways:

-

The value of Nigeria’s imports has more than tripled between 2015 and 2021—a seven-year period! More startling, Nigeria’s imports in the first quarter of 2021 (₦5.9 trillion) were almost as large as imports for the entire 2015 (₦6.7 trillion).

-

When we account for inflation, the exchange rate and our population, imports still grow. When we also account for exports, imports are higher and grow faster than exports. In 2015, imports were just 70% of the value of exports; by 2021, imports were larger than exports (110%).

- However, relative to her African peers, Nigeria is not a particularly prolific importer. We trail South Africa and Egypt while dominating Kenya, Ghana, and Angola. Looking beyond the continent, unsurprisingly, Nigeria’s

But it is a truth universally accepted by Nigerians that we import too much. We are import-dependent. We love foreign goods.

I jest.

But so do proponents of this obstinate idea. In 2019, Audu Ogbeh, Minister of Agriculture at the time, caused a stir when he accused Nigerians of importing pizza from the United Kingdom. Speaking at a Senate committee on agriculture, the Minister explained, “Do you know, sir, that there are Nigerians who use their cellphones to import pizza from London; they buy in London and bring it on British Airways in the morning to pick up at the airport. It is a very annoying situation, and we have to move a lot faster in cutting down some of these things.”

If importing pizza doesn’t scream import dependence, I don’t know what does.

Beneath these frequent complaints is a simple premise: until Nigeria weans herself off imports, she will never develop. After all, no country that imports too much will ever develop properly.

Try to ignore the latter claim's absurdity because today’s article challenges the first half. Does Nigeria really import too much? Let the data decide.

Imports are growing

When you look at import data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the first thing that jumps out is that Nigeria’s imports have grown steeply in recent years.

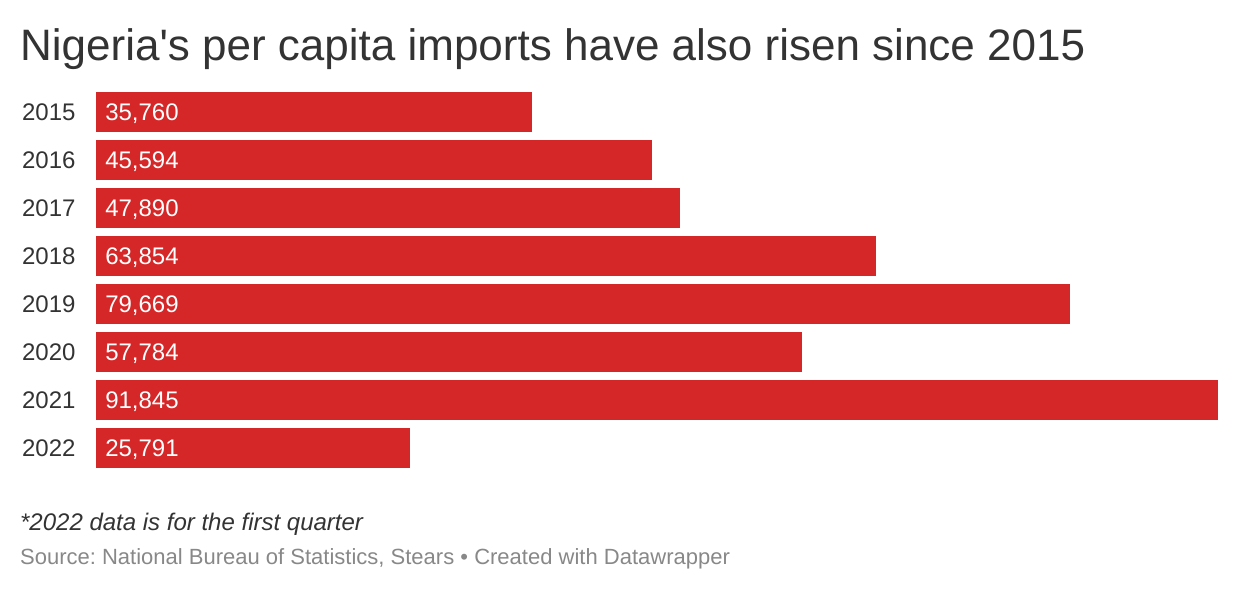

Imports more than tripled between 2015 and 2021—a seven-year period! More startling, Nigeria’s imports in the first quarter of 2021 (₦5.9 trillion) were almost as large as imports for the whole of 2015 (₦6.7 trillion).

Then again, we should expect this. Based on the most recent estimates of population growth, Nigeria may have added 40 million more people to its population in those seven years. More mouths to feed explain more imports.

But imports have also risen in per capita terms. Specifically, Nigeria’s 2021 per capita imports were 2.5 times greater than 2015 levels.

You could rightfully argue that if we account for population growth, we should also consider inflation and general expansion in economic activities. The best way to do this is to rebase imports by nominal GDP, allowing us to account for both inflation and the size of the economy.

When we do so, we discover that imports are still rising, even as a percentage of nominal GDP. In fact, if the Q1 2022 import trend extends to the rest of the year, Nigeria’s 2022 import-GDP ratio would be almost double what it was in 2015.

So far, the import-dependency camp is winning. But the tide may turn when we account for the most important economic variable in international trade: the currency.

We all know how badly the naira has lost value in the last decade. As the currency depreciates, the naira value of imports grows. Even if Nigerians are still importing the same $100 worth of toothpicks, the naira value of those imports will keep growing.

Unsurprisingly, dollarising Nigeria’s imports erodes a lot of the growth—but not all.

Nigeria’s imports have definitely risen from 2015 to 2021—the 2021 value is more than 50% greater than in 2015. And if the Q1 2022 trend persists for the rest of the year, Nigeria’s 2022 dollar imports will be 65% greater than in 2015.

Imports are still growing

At this point, the import-dependent camp can still make a fair case. A 50% increase in the dollar value of your imports in just seven years, especially when the currency has depreciated significantly and living standards have stagnated does indeed point towards a country indulging itself in imports.

But looking at imports alone is disingenuous. Like P-Square, imports come as part of a pair, so we need to look at how Nigeria’s exports have evolved before finishing our assessment.

Nigeria’s exports have been rising in naira terms, basically doubling between 2015 and 2021. But when we dollarise exports, we get a different result.

Nigeria’s 2021 dollar exports are slightly lower than 2015’s. That’s quite a change from the import trend. But there’s another important insight to glean from the chart above: volatility. Nigeria’s dollar exports are all over the place, declining from $49 billion in 2015 to $31 billion in 2017, then almost doubling to $61 billion in 2018 before dropping to $47 billion in 2021. There’s no real trend, just numbers. Remember this; it will be relevant later.

Going back to our original analysis, we can already see that while imports have been rising in every way, exports have not, at least in dollar terms. We can go further and directly compare the two by looking at imports as a percentage of exports, as shown in the chart below.

From the chart, we can almost conclude that imports have risen relative to exports. In 2015, imports were just 70% of the value of exports; by 2021, imports were larger than exports (110%). Therefore, imports must be rising faster than exports.

As conclusive as this data is on the growth of imports, it raises another question: is the observed trend a feature of Nigeria’s imports or Nigeria’s exports?

Think about it this way, if I compute imports as a percentage of exports over time, any change in my result can either be attributed to the behaviour of imports, the behaviour of exports, or both.

This is where the momentum swings towards the pro-imports camp because we have good reason to believe that Nigeria’s poor export performance is making the growth in imports look excessive.

Remember how I highlight the volatility in Nigeria’s exports? That’s the crux of the problem here. Notice even how that volatility manifests in the last chart we showed (imports as % of exports)—in 2015, imports are less than exports, by 2018 they are greater than exports, but in 2018 they are less than exports again, and by 2020 they are greater than exports.

It’s a yo-yo.

And exports are the cause. To show this, here are two charts. The first shows the annual growth of imports, and the second shows the annual growth of exports. Spot the chart with the more jagged bars.

Numbers tell a similar story. When we estimate the standard deviation of Nigeria’s annual import growth (standard deviation is the preferred measure of how dispersed or diverse a dataset is), we find that export growth (0.42) has a higher standard deviation than import growth (0.27). Although these numbers seem close, exports have a standard deviation that is 50% greater than imports, so in crude terms, we could argue that exports are 50% more volatile.

Importantly, the data and charts are backed up by real-world experience.

Nigeria’s exports are predominantly oil & gas products. In 2021, 89% of all exports were of the oil & gas variety. We have always known how volatile global crude oil prices are (that’s why the Federal Government created the Excess Crude Account). Still, in recent years, we have also accepted volatility in domestic oil production, thanks to increasing oil theft, declining investment in oil fields, and OPEC quotas. The result is that Nigeria’s exports are extremely volatile and depend on factors beyond our control.

We have fewer reasons to believe that imports are anywhere as volatile. Astute followers of Nigerian affairs may point to the recent land border closures and how that may have affected imports. Still, the reality is that road transport accounts for a fraction of official imports (or exports). In the last few years, less than 1% of Nigeria’s imports have been transported by road.

Putting all of this together, what does this mean?

Imports are indubitably growing faster than exports. And whether or not Nigeria’s import growth is unusual or excessive, Nigeria’s export performance is categorically poor due to the volatility of oil exports. If exports were healthier or more stable, import growth would not look excessive. This final point is more debatable and worthy of further exploration, but it is an important reminder that we miss the real story if we look at imports in isolation.

Nigeria’s imports vs other countries

We have seen so far that Nigeria has been importing more and more over the years, especially against our inability to export consistently. Does this mean we rule in favour of the import-dependency myth? Not quite.

The second part of our analysis requires us to compare Nigeria to other countries to see if we are importing above our station.

One thing to note is that all of the data before this point is from domestic institutions (Central Bank of Nigeria or National Bureau of Statistics) so there is consistency that allows us to make direct comparisons. International economic data is more dispersed, so you have to use multiple sources. The problem is that different sources use different methodologies, so you always need to be wary when transforming or comparing data. For example, we can get 2020 import data from one place (Observatory of Economic Complexity) to make direct comparisons. Still, it doesn’t have reliable GDP estimates, so we need to get them from another place (Worldometer).

Methodological differences between the two sources could lead us to error even without us realising it. In this case, we have a more practical problem: the trade is from 2020, while GDP data is from 2019. Thankfully, the time inconsistency does not matter much for today’s story because all countries have the same year for either trade and GDP. It may not be statistically perfect, but it will do the job. The crux of this ramble is that you should always scrutinise international comparisons a bit more. It’s sort of like getting different tailors to measure different parts of your aso ebi—it’s not a problem per see, but you’re likely to find yourself with some mismatched clothing at some point.

The next issue is to figure out which countries are worth comparing. This is more important than it first sounds, as, too often, we make international comparisons without context in Nigeria. Few things sound as impressive as “This is how they do it in Egypt” or “Nigeria has a higher unemployment rate than Brazil”, but we need to take a step back and confirm that the comparison is valid or useful. This failing plagues policymaking as it can lead to misguided aspirations or emulating the wrong country.

So, which countries do we use here? The easy answer is the Big 4 in Africa, as those are Nigeria’s benchmark countries on the continent. We toss in Angola because it has important similarities as an oil exporter (but not much else). However, our analysis will be limited if we only compare to African peers, so we need others. I put forward the BRICS (excluding South Africa as it is already covered) as they should be the gold standard for any developing country. The best-case scenario for Nigeria is that the way the BRICS look today is a preview of Nigeria’s future, so they offer a useful comparison.

To further enrich the comparison, we also include a cohort of non-African countries that are most comparable to Nigeria when it comes to wealth (GDP and GDP per capita), as shown at the bottom of the table below.

What’s the verdict?

Let’s look directly at import data across the comparison countries.

Relative to her African peers, Nigeria is not a particularly prolific importer. We trail South Africa and Egypt while dominating the other three.

Unsurprisingly looking beyond the continent, Nigeria’s imports pale compared to the BRIC countries.

The China comparison is almost comical—their imports are thirty times greater, but even Brazil’s is three times the size of Nigeria’s.

Finally, we can look at the “peer” non-African countries.

Again, Nigeria does not stand out. Our imports are pretty similar to Pakistan’s, and we import a bit more than Colombia, but we clearly aren’t in the same league as the Philippines or Indonesia.

So far, this international comparison suggests that Nigerians have a lot to learn about importing from their so-called rivals.

Earlier, we accounted for factors like inflation, currency depreciation, etc., when analysing the import trend, so we should do something similar here. The important thing to account for is the fact that all these countries have different economy sizes, so we ought to rebase by GDP.

What happens when we compare Nigeria’s imports % of GDP to other countries? This time, let’s look at all the countries at once.

The answer jumps out at us. Nigeria’s import tendencies are slightly below average across all the comparison countries (the group average is 17%). Moreover, Nigeria has the same import-GDP ratio as India, Russia, and Indonesia. We might as well toss in Colombia and China since they are so close.

Clearly, there is nothing unusual about how much we import, given the size of our economy. Looking at the data, we can come to contrary conclusions.

One conclusion is that Nigeria is not importing enough. This view is backed up by the fact that our import-GDP ratio (14%) is lower than the group average (17%) and much lower than countries spanning from Ghana (27%) in our neighbourhood to the Philippines (34%) in the pacific.

The opposing conclusion is that Nigeria is importing just as much as it should, given the size of the economy. This is supported by the cluster of countries around the 13-14% import-GDP mark (Pakistan is not too far away on 17%) and the identity of the specific countries in that cluster.

While it is tempting to pay more attention to our African peers, geography does not equate to similarity, and the other country groups are arguably more relevant. Remember that the BRIC countries (South Africa is considered part of the African cohort here) ought to show us our future. Three of the four have nearly identical import-GDP ratios to Nigeria.

Furthermore, the final group of countries was selected because their living standards are most comparable to Nigeria’s, so we should expect people (and businesses) in those countries to behave most similarly to Nigerians. Again, three out of five have similar import-GDP ratios to Nigeria, suggesting that our behaviour is normal.

Moreover, we can identify obvious explanations for the two exceptions. Iran’s trade patterns will always be funny, given that all the trade sanctions imposed by the United States have made the country more insular than neighbouring states. Meanwhile, the Philippines is an archipelagic country off the Pacific coast, so you would expect them to be more import-dependent than mainland countries.

Weighing up the opposing arguments, I am more convinced by the idea that Nigeria is somewhere around the goldilocks point and our imports are just right.

Where does all of this leave us?

First, we looked at Nigeria’s import trends to determine if we really have an import problem. The conclusion was clear: whichever way you slice it, Nigeria’s imports have been growing since 2015. However, we saw that the volatility of Nigeria’s exports raises the question of whether this import growth is unusual or just looks that way because Nigeria is failing at exporting.

Meanwhile, when we compared Nigeria to benchmark countries, we could reach either of two conclusions: either Nigeria doesn’t import as much as it should, or it imports just as much as it should. Whichever of these you prefer, when combined with our earlier doubts, we now have more confidence in the idea that whatever import growth Nigeria has seen is ordinary and not enough to warrant claims of import dependence.

It took us a while to get there, but when you look at the data closely enough, Nigeria beats the import-dependence charge.

Bring your pizzas and toss me a slice.