For most of President Buhari's eight-year tenure as president of Nigeria, he was pretty confident that the path to Nigeria's revolutionary growth was agriculture. He asked the youth to return to the farms and even attempted to bring back cattle grazing routes.

Farming (subsistence farming) was his master plan to raise 100 million Nigerians out of poverty. It's not a far-fetched idea to be fair. After all, agriculture reform in China formed the foundation for the Asian country's rapid growth and development. As we will soon see though, the real secret sauce for meaningful growth comes from a different part of the economy—manufacturing.

Key Takeaways:

-

Historically, manufacturing has been the secret to structural growth in countries. It is what made the US and Britain large economies and responsible for China's 20x economic growth in 40 years.

- However, given how much manufacturing has changed in recent times due to innovation and

Going by many theories of development and history, one way to achieve economic development is by exiting agriculture and becoming an industrial superpower. One of the most prominent ideas to support this is Rostow's stages of growth theory which says that for a country to grow, it needs to move from dedicating a significant portion of its capital and labour from agriculture to manufacturing and then services.

Manufacturing made Britain a world superpower during the first industrial revolution. The US became the largest economy globally through industrial expansion, and China grew its GDP per capita 20x in less than fifty years after its workforce moved from the agriculture sector to manufacturing.

The formula is: if you want to grow fast, start producing for the world. But is this still the case? Many say the digital economy is the next frontier, and might even allow countries that are still developing today to leapfrog into the next stage of growth. Therefore, today's main question is can the digital economy increase Africa's growth like manufacturing did for the west?

Before we answer these questions, let's take a detour to understand why manufacturing is so instrumental to growth.

Producing your way out of poverty

One of today's most intriguing industrialisation stories worldwide is China's. Industrialisation here is through large-scale and widespread manufacturing.

In 1980, China chose to become the world's industrial powerhouse, which meant that it had to ramp up manufacturing and open up its industries to foreigners to buy its manufactured goods and set up factories. After rolling out its export-led industrialisation policies, China's GDP per capita increased 20-fold from $490 in 1980 to $10,500 in 2020. This got its economy growing by over 9% from 1960 to date while lifting 800 million people out of poverty.

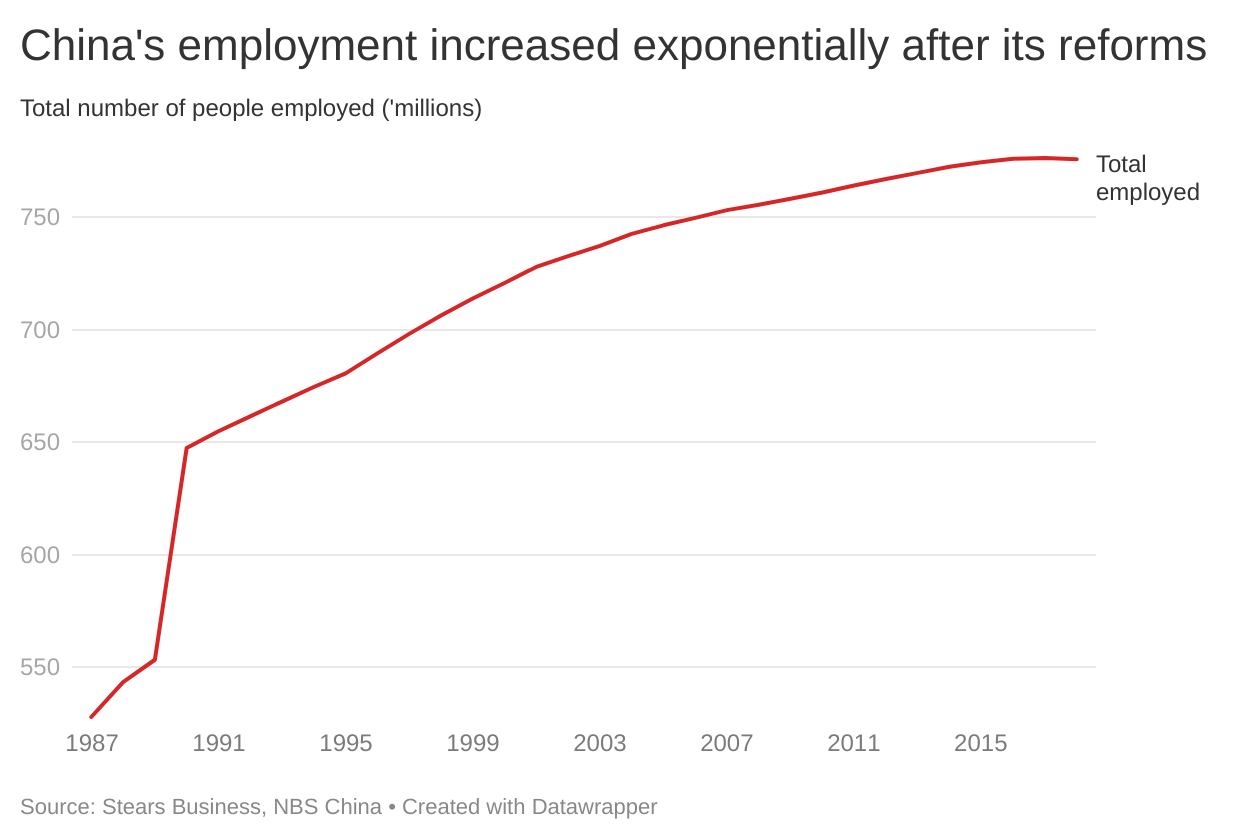

The Asian giant and second-largest economy in the world did this by investing in manufacturing; it transformed its agriculture sector and engaged the excess labour in the manufacturing sector, which has generated high growth for the country to date.

The East Asian Tigers like Japan, Singapore and Indonesia are another example of the magic of manufacturing in generating astounding growth in these countries.

But it seems this theory is being tested by emerging countries today. Africa seems to be taking a different development path. Between 1998 and 2015, services exports in Africa grew six times faster than commodities exports. Services are leading this growth wave. For example, Rwanda has experienced an average of 9% annual growth since the early 2000s without necessarily being an industrial giant.

Africa's mobile technology and digital services have also seen rapid growth. In 2019, the digital services sector contributed about $155 billion to the GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa. The revenue growth in the developing countries driven by mobile technology has also increased from $30 billion in 2001 to $1.4 trillion in 2019, a 45x growth in less than 20 years.

It's important to point out the amount of growth that digital technology has made possible. We have previously noted how the digital economy can contribute significantly to job creation. While there is little labour market data in Nigeria to support this idea, data from Jobberman shows that the IT & Telecoms industry recorded the highest level of job supply (14%) between July 2020 and July 2021. In addition, the fundraising amounts that happen almost every week prove that this part of the economy can still attract foreign investors, even as traditional investors lose interest.

So, it looks like the digital services sector has started contributing significantly to the growth of emerging economies. The question now is, is it enough to generate high and consistent growth like manufacturing?

It's hard to tell, and many countries are unsure whether this newly found path to development is sustainable. The digital route is now questioned more than ever because the world might be headed to a recession, which will mean even risk-loving investors like venture capitalists will start to seek safer havens (at least until all the uncertainty dies down).

But it's not enough to speculate about whether growth from digital technology is sustainable or not. We have to weigh the performance of the technology (and services in general) against the various features that made manufacturing successful to see if technology can replicate the kind of success that manufacturing has generated in the past.

We need to look at the key features that made manufacturing successful: its ability to employ many low to moderately skilled workers, its export potential and the spillover effects to other sectors.

Let's talk a bit about these features.

Growth through the people

An excellent place to start is the ability of manufacturing to generate employment in a country. It's almost impossible to talk about structural growth and development in a country without talking about employment.

Whenever a country is growing, especially when the growth is transformative—moving from low to high income—it is usually a result of increased consumption. Consumption increases when people are gainfully employed.

When industries open up, excess labour migrates from agriculture to the manufacturing sector, improving their skills and earning more. The more they earn, the more they consume.

For example, when China began its industrialisation phase, its labour force distribution changed from most of its labour force employed in agriculture to being engaged in the manufacturing and services sectors instead.

However, the issue with increased manufacturing growth is that as manufacturing expands in countries, the share of people employed in the manufacturing sector will decline, primarily due to a rise in innovation—the improvement of a process to make it more efficient, and robots taking over people's jobs. For instance, while manufacturing output in the US has increased by at least 5% since 2000, more than five million jobs have been lost.

The US Bureau of Labour statistics cites skills mismatch as one of the core reasons for the employment decline. There are job openings, many of which are targeted at high skilled labour, but not enough people to fill those roles. Therefore, low-skilled workers are getting left behind due to innovation in the manufacturing sector.

So while manufacturing has the potential to employ many people at the onset of industrialisation, as the industries innovate and strive for more efficiency, labour is replaced with capital which is typically cheaper.

So how does the digital economy measure up in terms of employment? Very well.

Remember the Jobberman statistic I referenced earlier about the digital economy becoming the destination for more Nigerian jobs? That's just one data point. US jobs market data also tells us that startups accounted for almost all the jobs created in the economy in the past decade. High-growth startups are perfect job creators because not only do they create jobs today, but they also create more jobs in the future. As teams raise more money so they can achieve product-market fit and scale, they will employ more people. Of course, the challenge here is ensuring that the right education system exists to supply the skilled labour this ecosystem demands, but that is an article for another day.

Local industry, global market

So, the first feature of the manufacturing sector that makes it generate significant growth is that it carries the labour force along. The scale of the manufacturing sector makes it able to employ many low-skilled workers simultaneously till it innovates and sheds off its labour.

This large-scale manufacturing requires a large market for its output. On the one hand, countries with large populations benefit from selling to their population. But it's not enough to have a large population; that large population has to have the purchasing power to afford the products.

Shoprite's experience in Nigeria is the perfect example of how a large population doesn't always equal a large market. Before entering the Nigerian market in 2013, the CEO of Shoprite at the time was quite optimistic about the Nigerian market. "Even if you have 60% of the population living in poverty, 40% of the Nigerian population is still bigger than the South African population", Mr Whitey Basson, Shoprite's former CEO, said. Out of the 800 stores initially slated to launch in Nigeria, Shoprite could only do 25 and even had to close some down.

A point we've echoed time and time again is that Nigeria has a large population but a small market, and this is why export is essential.

When China decided to start its industrialisation drive, it understood that its population, although the largest, was not enough to consume all the output from the industries. Therefore, it exported most of its industrial output, contributing to economic growth.

This is one of the benefits of core manufacturing; its potential for trade expands the market size of the industries and generates growth. At this point, it's important to note that not all industrialisation—large scale manufacturing, can create the kind of structural growth we've been clamouring about throughout the article.

Industrialisation usually takes two different forms: export-led and import substitution industrialisation.

The model China adopted (export-led industrialisation), aims to produce for the world. As we established earlier, one of the reasons manufacturing generates a high growth rate is the economies of scale. Manufacturing is done on a large scale and requires a large market to justify its size, usually from exports.

Latin American countries adopted import substitution industrialisation (ISI) to become self-sufficient by typically imposing restrictions on foreign trade and prioritising their local market over foreign markets. An example is Indonesia's recent export ban on palm oil.

Some countries in Africa and Eastern Europe are also victims of this form of industrialisation. While this might be politically popular—governments usually like to prioritise their local markets, it does not generate the kind of growth that transforms a country from low income to high income. This is primarily because of the limited size of the market, which prevents them from enjoying the economies of scale the international market affords them. Also, without foreign competition, domestic industries might fail to innovate or become more efficient.

Therefore, export-led industrialisation is usually preferred. However, a significant downside to export-led manufacturing is the impact of local shortages on global value chains. We saw that in 2020 and are still reeling from its effects today, like the shortage of workers on global food prices and coronavirus lockdowns on manufacturing output from China and more. While export-led industrialisation creates specialisation, which is good for trade and growth, the world suffers once the plug is pulled on one of the suppliers.

The volume of trade in the technology ecosystem can be tricky to measure because the services enjoyed are intangible, unlike trade in goods. However, technology output is primarily export-led because it is easy to provide technology services to people worldwide. Like this article, you could be reading it from the Stears office in Lagos or somewhere in Mumbai.

Taking a cue from the World Bank, we can use four metrics to measure trade in digital services: cross-border supply, consumption abroad, commercial presence and the presence of natural persons. Cross border supply is when you provide a service to a client abroad without being in that country physically; like Twitter or Spotify, which provide their services to Nigerians without a physical office.

Consumption abroad is when a foreigner enjoys a service in another country, like tourism or schooling. Commercial presence is a service provided through a subsidiary firm, and the presence of natural persons is when a person travels physically to provide a service.

Given the nature of these measurements, services may be easier to trade across borders; however, they may be difficult to track, which means that their contribution to GDP may be underestimated. Due to its intangible nature, it is easier to trade in services worldwide, which means it has as much potential for export as manufacturing, maybe even more.

Spillover effects

The final feature of manufacturing that makes it able to generate the scale of growth it does is that it ushers in innovation and investment in innovation, which spills over to other sectors. Remember, innovation is improving the production process to make it more efficient. This could either be by introducing new processes or products.

Innovation, in this case, could be imported from other countries or could be developed internally through heavy investment in research and development (R&D). Increased innovation leads to more efficiency in the industries and more output.

The innovation used in manufacturing usually doesn't just improve the output of the factories alone but spills over to other sectors. For instance, lean production, which Japan introduced, is now being infused into many services sectors, even education. When innovation is introduced to improve the efficiency of factories, it is adopted by other sectors and leads to efficiency all round.

Spillover effects could also come in the FDI inflows into the country. As more factories open up in the country, demand for other goods and services increases—because people are wealthier, which results in the influx of even more companies that may not be industry related.

This leads to FDI inflows to several sectors of the economy. For instance, China's FDI inflows increased from $46 billion in 2001 to $135 billion in 2017. This creates employment and growth in other sectors apart from the manufacturing industry.

The spillover effects manufacturing enjoys is not precisely because of manufacturing in itself but due to the impact of technology and innovation in the manufacturing sector. Digital technology has derived demand, which means that people don't exactly want the technology in itself but what the technology can do, which is in various sectors. For example, when people adopt big data technology like drones on farms, it's for the technology itself. Still, it gives the farmer precise information about the farm because of the value.

Likewise, people don't adopt e-commerce for the sake of it but because it makes trade more seamless, improving the output of the trade sector.

Hence, the technology in the digital ecosystem has a greater chance of generating the spillover effect because it improves efficiency in other sectors. Therefore, the spillover effects experienced in manufacturing are bound to also occur in the digital technology sector.

Industries are changing

What makes manufacturing work is employment, export potential and spillover effects. However, industrialisation has changed over the years, and we established earlier that manufacturing doesn't create as many jobs as it used to. Beyond that, the disruptions in global supply chains caused by pandemic induced lockdowns in China and Russian sanctions have encouraged countries to become more self-sufficient. For example, we have recently seen Indonesia clamp down on palm oil exports so they can prioritise the domestic economy.

This means that the export potential for manufacturing might be shrinking. Although we don't expect to see a huge decline in the demand for manufactured goods, industrialisation might not reap the benefits it did in the past.

Therefore, emerging countries can't easily replicate past successes to generate the kind of growth they desire. So, many emerging countries are consequently looking towards technology that has been delivering steady but strong growth to replace manufacturing.

One common argument against emerging countries skipping the manufacturing step to expanding their services sector to drive structural growth is that it creates premature deindustrialisation. This is when a country reduces its manufacturing sector output too early, such that other sectors cannot employ its population. When the previously employed people in low productivity sectors like agriculture cannot get manufacturing jobs, they move on to the services sector. However, without the skills required to get employment in the highly skilled services space, they settle for smaller jobs that may not drive the desired growth.

Although manufacturing has guaranteed growth in the past, it has transformed significantly, and emerging economies might not benefit from it as developed countries did in the past. However, the digital ecosystem has continued to have stable and consistent growth, making it poised to generate the kind of growth that manufacturing would typically generate.

This is a long way from our president's desire for everyone to return to farming, but if Nigeria can hack the digital space, it might have a real shot at stable and sustainable growth.