Central banks were designed to be powerful.

I mean, let’s just take all the drama that the US Federal Reserve (America’s central bank) has been causing as a starting point. Ever since the US Fed signalled its intent to battle the rise in inflation by raising interest rates, the global stock markets have been in disarray, followed by multiple predictions about a looming recession. To see the link with the stock markets, a key thing to remember is that traditional investors aren’t too hot on uncertainty. So, with the Russia-Ukraine crisis as context, in theory, rising US interest rates typically mean that these investors will seek safer havens (higher interest rates make government bonds more attractive) to store their wealth, at least until the dust settles.

Key takeaways:

- Central banks are designed to be powerful. Two key features that allow them to be powerful is their independence and ability to

In addition, when you go back to Econ 101, it’s easy to see why one of the central bank’s key tools—interest rates—can cause people to worry about the direction of economic growth. Central banks increasing interest rates (the rate that banks charge each other for loans) leads to an increase in the cost of borrowing for businesses and consumers. In theory, this should slow down the demand for goods, which ends up placing the brakes on inflation. Attempting to curtail inflation makes sense because it ultimately impacts the price we pay for everything from food to plane tickets. But central banks are often cautioned to adopt a gradualist approach when using interest rates to manage inflation. That’s because if interest rates rise too quickly, they can hamper demand, as consumers buy less, businesses reduce borrowing to fund investment, and overall growth in the economy slows (or worst-case scenario, turns negative).

Essentially, central banks are responsible for economic and monetary policy, as well as ensuring the soundness of the financial system. Even when you look at the CBN’s mission on its website it clearly states that the apex bank is committed to “delivering price and financial system stability and promoting sustainable economic development”. So, when I set out to write this article, the main point I initially wanted to prove was that central banks, including the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), are quite powerful. I basically wanted to show that for a long time, central banks have been expected to shoulder the greater part of not just economic management, but also the burden of post-crisis adjustment.

For example, one crucial reason central banks are so powerful is the fact that they can act independently and quickly. During periods of crisis or downturn, these two features can be particularly important. For example, the first economic response to the Brexit vote was at the next Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting—a group of policymakers who meet regularly to determine monetary policy. In the case of Brexit, the MPC members could unilaterally decide how economic policy would respond to Brexit almost immediately. This way, the Bank of England staved off the risk of doing nothing while the rest of the British government decided how best to respond.

And so, with this crucial role that central banks play in the economy, they have amassed some powerful tools.

Whether it’s the European Central Bank doing “whatever it takes” to keep the euro afloat, or like we touched on earlier, the US Fed directly intervening to ward off inflation, central banks can quickly go from zeroes to heroes in their attempts to steer economies through inevitable boom and bust cycles. I mean, we even have a CBN Superman article that looks at all the ways the CBN has directly intervened to provide cheaper loans to farmers and ended up as one of the federal government’s biggest creditors.

However, one simple and inalienable truth is that central banks by themselves, cannot resolve the underlying problems of huge debt overhang and economic imbalances that their countries face. You need some interventions on the fiscal side as well, otherwise, you risk chasing short-term gains while incurring long-term losses. One easy way to illustrate this is how Zimbabwe’s central bank kept on printing money (increasing money supply increases output temporarily, which can stall risks of a recession) until the country went into hyperinflation. This resulted in Zimbabweans paying as much as 2 billion Zimbabwe dollars for a loaf of bread.

So with these criticisms in mind, we will spend today talking about some key indicators that can show us why central banks aren’t the silver bullet to economic woes.

Let’s start with an obvious one—the relationship between interest rates, central banks, and inflation.

We talked earlier about the negative correlation between interest rates and inflation. That is, as interest rates go up and the high cost of borrowing makes its way through the economy, demand should cool and inflation will go down. That means, when faced with rising inflation, central banks should intervene to curb that effect.

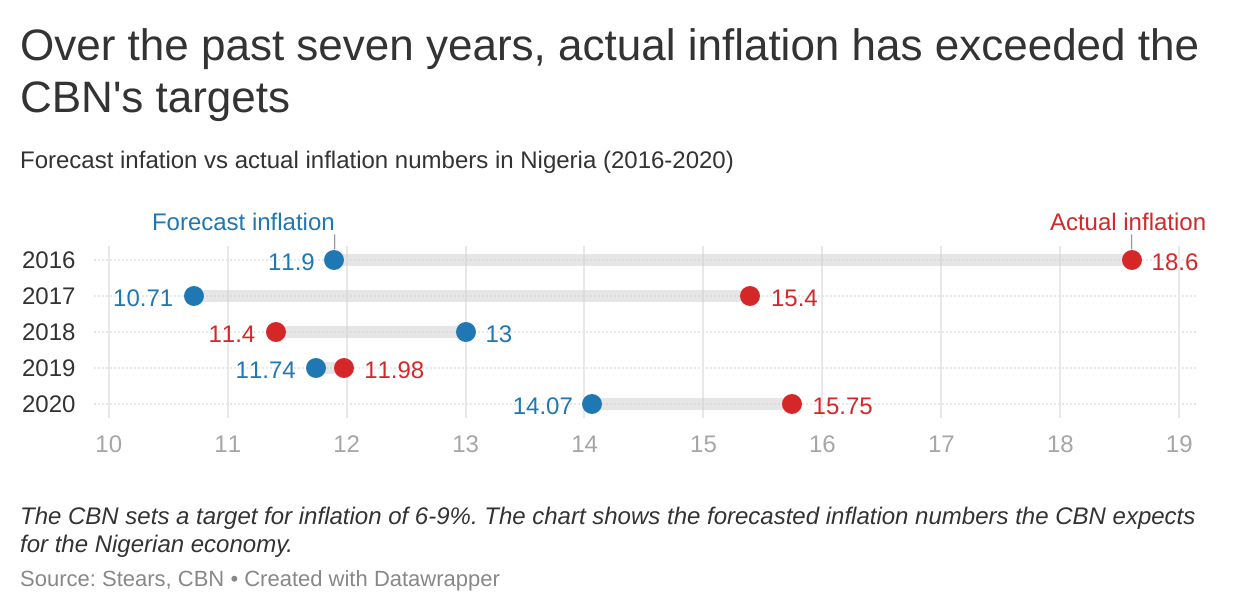

However, what we have seen in Nigeria’s case is inflation rising quite sharply, while interest rates have not changed much. In fact, it was only at last week’s Monday’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting that the CBN voted unanimously to raise the benchmark interest rate to 13%—the first hike in almost six years (and the first change in two years). Now you might be wondering why the CBN waited so long before intervening to curb inflation given we have had high inflation numbers for so long. In 2016, inflation levels were as high as 18.6%. In April the year-on-year change in inflation (compared to April last year) was 16.8%. At first glance, you could argue that the impact of the pandemic encouraged the CBN (along with other central banks across the world) to adopt an expansionary stance by keeping interest rates low. That’s because demand was already negatively affected by the slowdown in economic activity as a result of lockdowns, so any hike in interest rates would have been extremely detrimental and could have had the impact of slowing down the post-pandemic recovery.

The more convincing argument is that many people believe that central banks don’t have much impact in places like Nigeria.

For starters, there is a widespread belief that monetary policy transmission in Nigeria is supposed to be weak. The mechanism through which interest rates affect inflation mostly happens through the banking or lending system (remember interest rates affect the cost of borrowing). However, Nigeria’s banking system is oligopolistic (few players dominate with high barriers to entry). As such, banks have a lower incentive to be competitive, which means they don’t lower rates as readily as they raise them. So for all the fuss about the recent rate hike to 13%, I won’t be surprised if you ran into an economist at the CBN who does not believe the rate hike will pass through the economy. Of course you could challenge this person by pointing out that just the expectation of inflation is enough to lead to actual inflation. Unfortunately, for many Nigerians, inflation has now become synonymous with the economy. Mostly because at different times, the CBN has acted with little credibility, which has caused many to question its political independence. When you consider what I said earlier about central banks being so powerful because they can act independently, the irony basically writes itself.

There’s also the fact that our problems are too structural for a bank to deal with, and is honestly a simple theory that can explain why Nigeria always has inflation. But that shouldn’t be too much of a problem because inflation can happen when the economy is growing too fast. By their definition, developing countries like Nigeria are meant to grow fast. The thinking is that developing countries have a lot of catching up to do and grow quickly by copying the technologies in advanced countries. It’s where the term “leapfrog development” comes from. So, as poor countries leap forward and grow, more people find jobs, their incomes increase, they demand more goods, and businesses increase their prices to accommodate or take advantage of the extra demand.

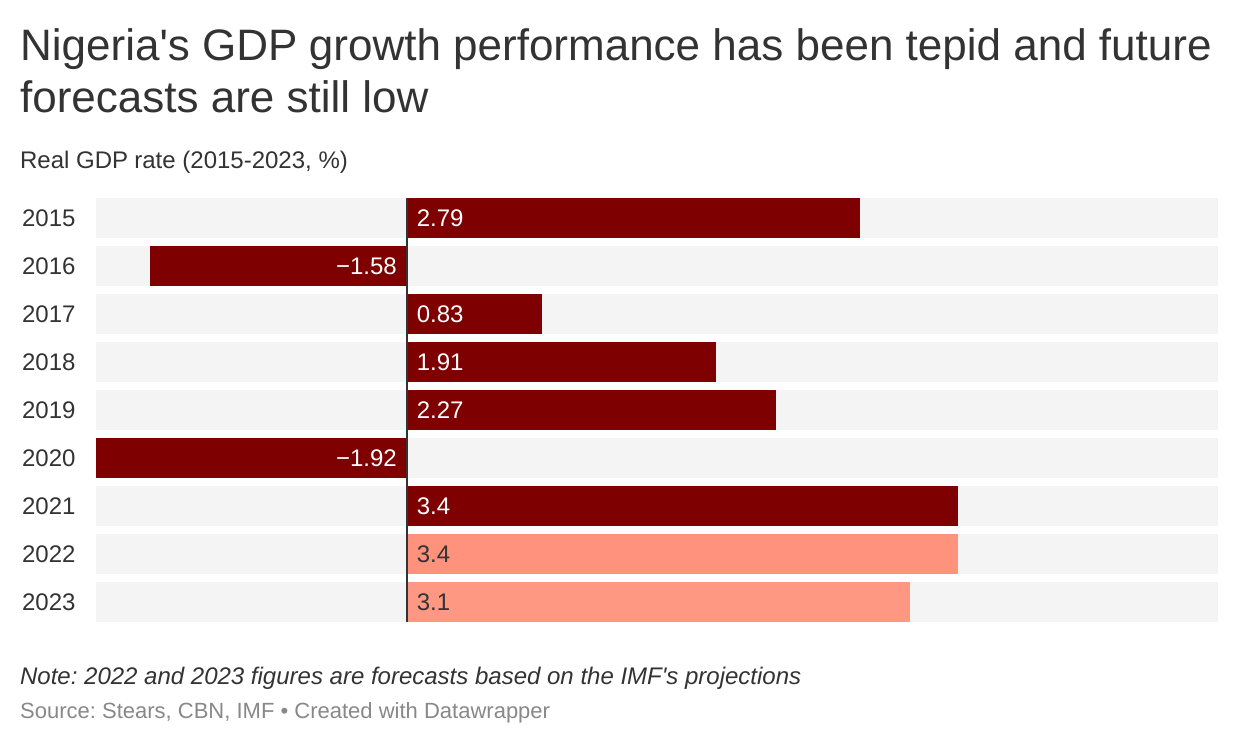

The downside to this is that if you have high inflation but you are also struggling to cancel this out with faster growth, you end up in a lose-lose situation. This is the exact situation that Nigeria finds itself in, unfortunately. Even with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revising our country’s growth forecasts upwards (from 2.7% to 3.4%), that’s still low for a developing country with double-digit inflation. For context, in its heyday, the Chinese economy reached a historical high of a 15.2% annual growth rate. Needless to say, upward growth projections aside, the outlook for the Nigerian economy remains tepid at best.

Of course, all of this isn’t necessarily the CBN’s fault. But it speaks to the heart of the point we discussed earlier when we said central banks shoulder a great burden when it comes to economic management. This can be worrying for many reasons, the main one being that other policies that matter more for sustainable growth and development (see: supply-side policies) tend to take a backseat. It’s not just a Nigerian phenomenon though. Back in the era of the global financial crisis, the drastic measures taken by central banks in developed countries such as quantitative easing were massively criticised. During this period, we saw the balance sheets of central banks like the ECB rise to massive proportions as they directly intervened to save the day.

In Nigeria, we have also seen how an overreliance on monetary policy for economic progress might cause many to wonder if the CBN Governor is the only policymaker in the country (he is not). Think of the structural challenges I said Nigeria battles with like bad roads, inadequate storage for goods and disruptive policy changes like border closures. Even without a pandemic, these induce supply constraints that can feed into higher inflation. Simply waiting for the CBN to manipulate interest rates would make little to no difference because the supply problems will still exist—it is difficult for us to make as much as we consume.

Then there is the CBN’s obsession with the exchange rate. You cannot talk about the CBN’s undue influence on the Nigerian economy without talking about its supply and demand-side management of our dollars. Remember what I said about investors seeking safer havens during times of uncertainty? Well the US Fed rate hike also has implications for currency devaluations on this side of the world.

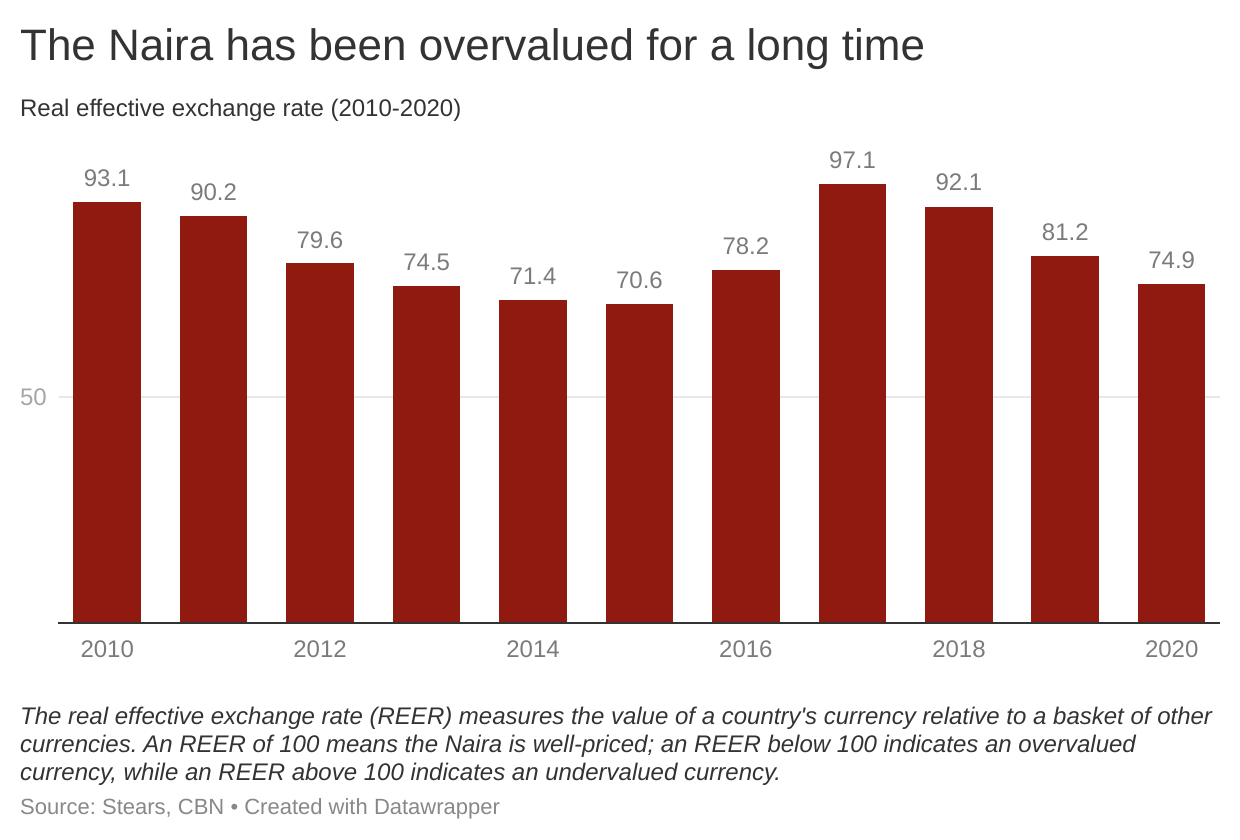

For a long time now, people have criticised the central bank’s naira peg to the dollar as unrealistic, given the wide disparities between the actual value of the naira, and the price the CBN currently fixes it at.

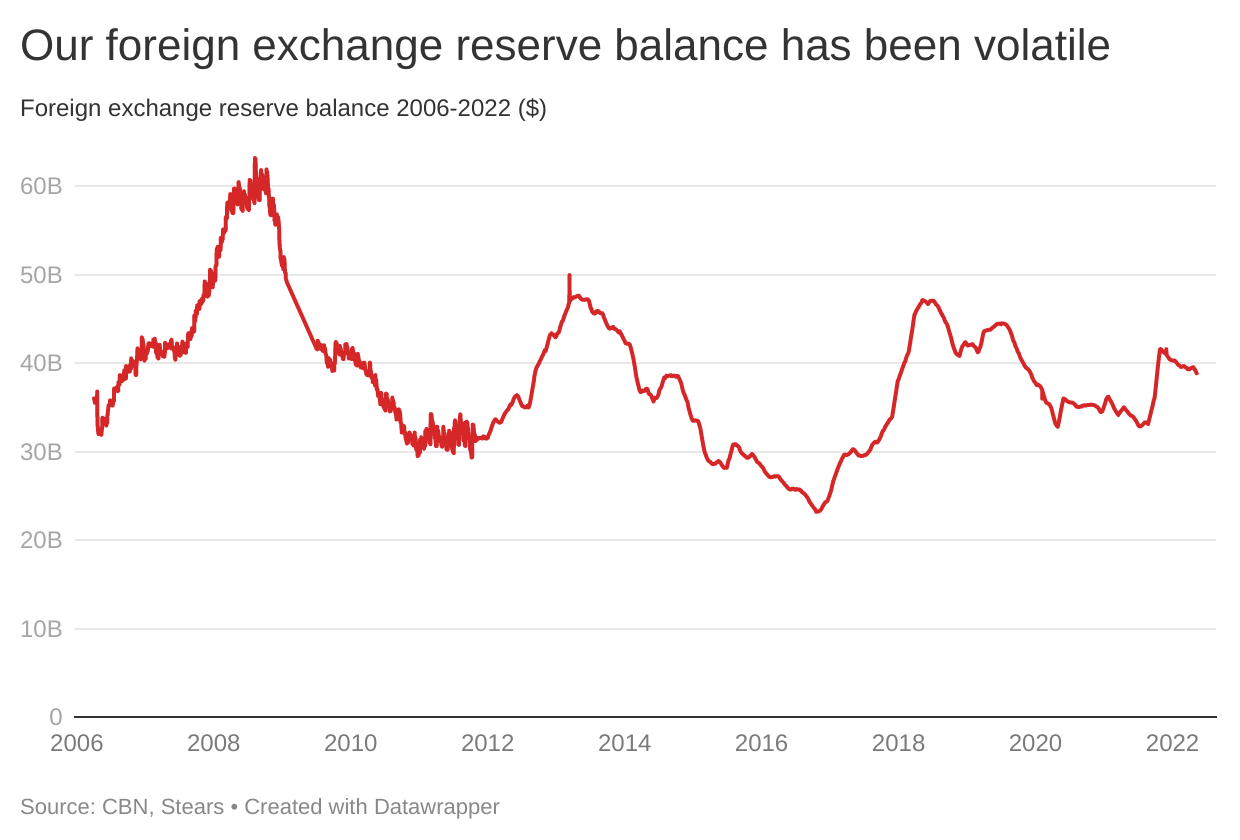

The fixed exchange rate regime the CBN adopts has been sustained so far by the CBN drawing on its scarce foreign exchange reserves. However, these reserves have been volatile over time, especially as our main source of FX earnings (oil exports), has been dwindling due to oil production issues stemming from vandalism and theft.

Moving away from the exchange rate for a second, I want us to look at another area where the central bank wields its power that we probably don’t talk about enough. The banking sector.

Nigeria’s banking sector is one important contributor to the country’s economy. In 2021, the market size for the finance industry was $13 billion. For context, the cement industry contributed $14 billion and agriculture (the country’s largest employer contributed $88 billion).

It is also a key industry that the CBN cares about—by its definition the CBN is the apex regulator for the financial services industry. That’s why aside from interest rates another metric that is closely watched by central bank observers is the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR). This is basically the minimum amount of deposits as reserves that commercial banks must have with the central bank.

Commercial banks typically exist to take our deposits (when we save money with them) and then lend out or invest them. It’s the main way they make money. This is actually an important monetary policy tool that is used to increase or decrease the economy’s money supply. So, when the central bank lowers the CRR, it’s giving banks more money to lend, which boosts the economy. Increasing the CRR does the opposite and helps to control inflation (less money chasing goods will place downward pressure on prices).

However, the CBN has been notorious for setting punitive CRR rates as part of its efforts to manage inflation in the economy. Remember what I said about interest rates being ineffective at reducing inflation in Nigeria’s economy. The CRR is meant to serve as an alternative. Needless to say though, high CRR rates don’t make shareholders happy because of their impact on banks’ profitability. Think about it this way, with a 27.5% CRR, for every ₦100 a Nigerian deposits with a bank, ₦27.50 is deducted. That leaves ₦72.50 for banks to play with (i.e. lend out to borrowers).

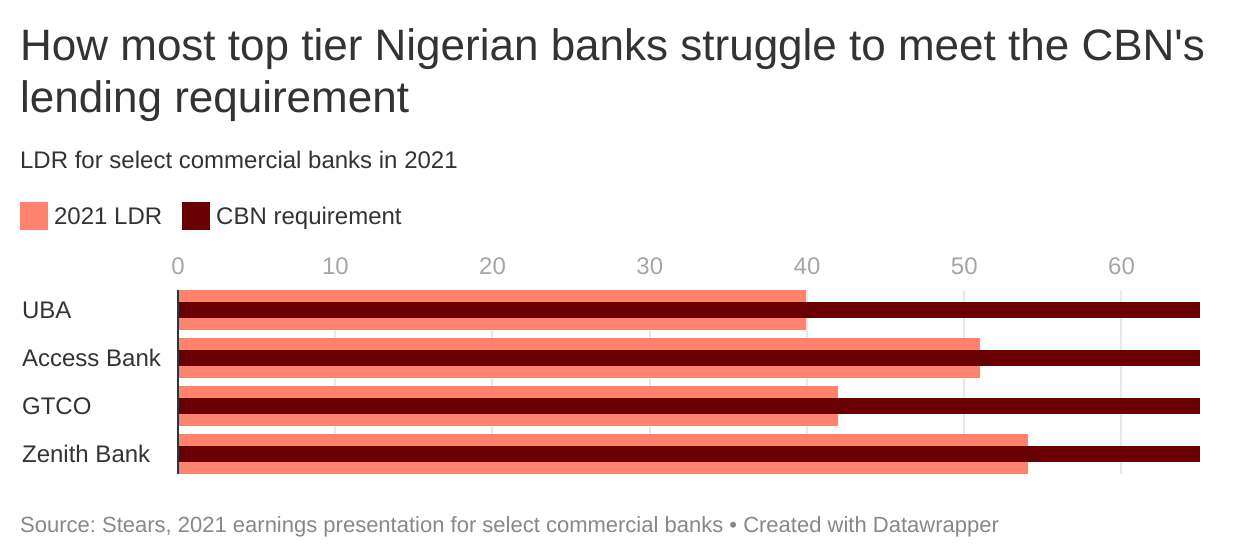

At the same time, the CBN has a directive for banks to lend at least 65% of their deposits, which it enforces by taking at least 50% of the shortfall when banks don’t meet the requirements. This is done to encourage access to credit for firms, which is needed for investment purposes. However, Nigerian banks don’t lend to businesses anywhere close to the rate that their emerging market peers do. Last year, UBA and GTCO gave barely 40% of their deposits, while Access Bank gave 51%. In contrast, banks in South Africa lent over 80% of their deposits. Again, we see the central bank stepping in to solve the low access to finance problem that a lot of companies in Nigeria battle with. However, because of the information asymmetry that exists and consequently discourages lending, even a CBN directive to encourage lending does little to move the needle forward.

In essence, the main thing I am trying to bring out here is that it is true that central banks and their many functions are important for our economies. However, one thing that has struck me as we contemplate the fate of the global economy is the hyper-focus on central banks and how their actions may or may not determine whether we slip into a recession or not. This worries me because, through a series of pre-and post-crisis decisions, we have placed additional functions on these institutions that might have yielded unforeseen and unwelcome consequences. For this reason, whether the highly anticipated global recession happens or not, we need to adopt a broader approach to policymaking that does not depend too heavily on the apex bank alone.