One thing you can count on in Nigeria is that the national grid will collapse.

Google “national grid Nigeria” and the top ten results will include the word “collapse”. The headlines will be related to “why the national grid collapsed again”. The term “again” there illustrates the general exasperation Nigerians feel with the national grid. You’ll also see words like “incessant” and “frequent” because the two things that are predictable about the grid are that it will surely collapse, and it will collapse unexpectedly.

-

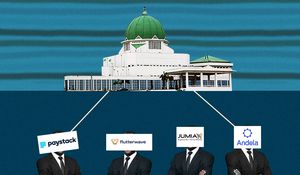

The Nigerian house of representatives voted in favour of a bill that will allow states in Nigeria to generate, transmit and distribute electricity in areas covered by the grid.

- It’s no secret that the national grid is unreliable and that the power sector suffers from liquidity issues. With the states in control of their power supply, state governments could create an enabling environment for the private

This feeling of exasperation is heightened because we don’t have a choice. When my laptop kept shutting down unexpectedly even after getting it fixed, I stopped complaining and got a new one. But with Nigeria’s electricity grid, all we can do is complain because it’s not up to us, the citizens; it’s up to the government to fix it. And not just any level of government; it’s the Federal Government.

This is because Nigeria’s 1999 constitution dictates that the state houses of assembly can only make laws concerning the generation, transmission and distribution of electricity in areas across the state that are not covered by the national grid. So, Lagos state, which is pretty much an urban state and covered by the national grid, cannot make a law to establish its own grid. This means Lagos state would have to rely on the national grid for its electricity even though it has the means to set up its own. You can imagine how frustrating it is when you have the solution to your problems but can’t help yourself because of a seemingly pesky rule.

However, last month, the National House of Representatives voted in favour of a bill for an act to “alter the provision of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 to allow States to generate, transmit and distribute electricity in areas covered by the national grid”. So, Lagos state might be able to have its power sector with its state regulators, meaning we won’t need to rely on the federal government to fix power issues.

But why is this amendment a good thing? What might states gain from the amended act, and what do individual states need to do to ensure they don’t end up with a system like the national grid? Let’s get some answers.

Designed to collapse

The grid’s job is to transport electricity over large distances. Generation companies generate electricity, which is fed into the national grid and transported to distribution lines and, from there, to our homes.

The national grid in Nigeria is managed by the Transmission Company of Nigeria’s (TCN) Independent System Operator (ISO). The ISO is an arm of the TCN, and its job is to coordinate, control and monitor the operation of the national grid to ensure stability. But this isn’t an easy job in Nigeria.

This story on Nigeria’s transmission issues breaks down the problems in detail. But two major issues concern this argument.

These issues are important because they’ll help us understand the grid’s limitations and why the states want to handle their own electricity supply.

The first issue is that supply does not equal demand, which causes grid instability, and eventually, grid collapse.

We already know that electricity demand in Nigeria outweighs electricity supply. Our generation capacities claim to have the ability to generate about 13 gigawatts (GW). This is called their installed capacity, and it is what their generation equipment could generate if there was enough fuel (gas or water) available. But what they actually generate is about 5 GW and what the grid can handle is about 7.5 GW. For context, Nigeria’s electricity demand for our entire population is estimated to be 180 GW.

So, why the differences? The difference between the installed capacity of the grid (13 GW) and what the grid can actually handle (7.5 GW) is caused by the technical limitations of our grid. Imagine that the grid is a pipeline for electricity because that’s essentially what it is. If the pipeline can only handle a certain amount of electricity, transporting anything more than that is a hazard. And because this is high-voltage electricity we’re talking about, any safety issues could cause significant loss of life and property.

But, we don’t even generate 7.5 GW; we generate about 5 GW. This difference has two causes. First, the generation companies don’t generate enough. Generation companies have an installed capacity of 13 GW, but this 13 GW depends on whether they have enough fuel. Nigeria’s generation capacity is 80% gas and 20% hydroelectricity generation. Gas generation requires natural gas, and there are major structural issues we discussed in a previous article, but basically, we don’t produce enough gas to maximise our electricity generation.

The second reason why we only generate 5 GW is related to the first reason—our famous liquidity issue. It would be hard to find any article on Nigeria’s electricity sector that doesn’t mention this issue, especially articles from Stears. But, the point is that the companies along the entire value chain (from generation to transmission and distribution) are broke. The distribution companies (discos) are the collection agents of the sector. Still, non-payment of electricity bills means that discos don’t collect enough money to pay generation and transmission companies for their services. So, even if the grid can transmit 7.5 GW, if Nigerians won’t even pay for 5 GW, there’s no reason to try to transmit 7.5 GW.

Policies like the service based tariffs have tried to solve this issue by mandating discos to supply a minimum amount of hours for a specific tariff. However, legacy debts owed to gas suppliers still affect the generation companies’ abilities to buy gas.

The second technical issue affecting the national grid is also related to the first issue of supply and demand. But this issue affects the grid’s ability to maintain stability when demand and supply don’t match.

The recent grid collapse (the second one in a month and the fifth this year) that happened a few days ago was caused by vandalism on a transmission line. Think of Nigeria’s transmission line like a row of dominoes. If one domino falls, all the dominos that follow will also fall. That’s basically how Nigeria’s national grid is designed. But it doesn’t have to be this way. It could be upgraded with new lines so that if one section of the grid is down, the electricity can be re-routed to another section to avoid interruptions. We could also have backup generators that can meet demand if some generation companies have gas supply issues.

Essentially, these are the major issues with the grid, and these are also the reasons why the states would like to handle their generation, transmission and distribution. But what would they gain?

Why do states want to generate their own electricity?

Last week, our knowledge editor wrote an article titled “Two things the Nigerian government must focus on”. His central argument was that governments have two jobs—coordinating the redistribution of wealth and aiding the private sector. We’ll focus on the second one.

Aiding the private sector means providing all the tools necessary for the private sector to thrive. This is crucial for economic growth and development. Without the right conditions for businesses to thrive, economic output will be limited. Coincidentally, electricity is one of the most important requirements for a thriving private sector.

Take manufacturing as an example. Electricity is crucial for this sector’s success. A state government like Anambra’s that wants its state to be West Africa’s next industrial hub needs reliable electricity to power businesses. But, electricity is also vital for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In a survey conducted by the World Bank, 27% of respondents said that electricity was their most significant obstacle to doing business in Nigeria, second only to lack of access to funding. According to another World Bank report, Nigeria’s unreliable power supply results in annual economic losses estimated at $26.2 billion, roughly 2% of our GDP.

With reliable electricity aiding the private sector, state economies would perform better. For business owners, savings on diesel and petrol costs would mean better profit margins. Business owners would be able to scale their businesses and create jobs for unemployed Nigerians. A boom in entrepreneurship would also mean better competition and increased innovation, increasing the range of goods and services available at more competitive prices.

According to Nigerian manufacturers, electricity costs make up about 40% of total production costs due to diesel consumption. So, steady electricity would save costs for manufacturers and significantly improve margins. Also, states could create jobs, increase foreign exchange earnings for the country by increasing exports, and stimulate entrepreneurs' growth.

So, any state government interested in helping its people will be interested in fixing its electricity supply issues.

But, some major obstacles could hinder these plans.

Funding and Right of way

In cities like Lagos, building transmission and distribution infrastructure would undoubtedly entail the destruction of buildings along the route, and building owners would need to be compensated. But, even getting their approval could be tedious. Because who would want the Lagos state government to displace them from their million-naira Lekki mansion to build a distribution or transmission line? And how many people would the government have to pay?

Securing right-of-way permission in Nigeria is hard work. Right-of-way (RoW) is the legal right to use a specific route on someone else’s land or property. RoW doesn’t just apply to electricity; it affects all infrastructure projects, from roads to pipelines and even internet cables.

It’s one of the major reasons why internet connectivity within Nigeria is so poor; securing RoW to pass fibre optic cables across the country is expensive and tedious. For electricity projects, it’s even worse because you can’t have buildings or any other types of structures under power lines.

This problem also affects extending or modifying the national grid. And it’s not just a Nigerian problem. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), one of the major challenges to constructing new transmission lines in the US is getting approval for new routes and obtaining rights to necessary land.

The second issue is funding. Electricity projects are expensive and typically cost millions of dollars. For instance, a 460 MW plant in Edo state cost $900 million to build. For context, Lagos state’s Internally generated revenue (IGR) in 2020 was ₦419 billion, the highest across the states in Nigeria. Building generation, transmission and distribution infrastructure will certainly cost a lot and require taking on loans and other funding sources.

Right of way issues aren’t easy to resolve, especially for electricity projects. And securing funding might not be difficult for states like Lagos, with clusters of industrial and residential consumers that are able and willing to pay for electricity.

But, securing funding and ensuring that the state power sectors work will require freeing the electricity sector from the government’s control.

How states can make their power sectors work

We know that Nigeria is a country that is addicted to price control, which means that the government likes to control the price at which essential products like fuel, electricity and even dollars are sold. But, this just creates market inefficiencies where supply and demand do not match. The inefficiency is evident in the national electricity market—our electricity situation cannot improve. On the one hand, the non-cost reflective tariff means that market players can’t generate enough revenue to cover their costs. On the other hand, the sector cannot attract funding.

To secure funding, states must show that their electricity markets can generate revenue. The primary blocker to funding in the power sector was that tariffs weren’t cost-reflective because the government was trying to protect citizens from high electricity tariffs. This combined with the poor payment for electricity from consumers, meant that any funding to the power sector would not result in any returns for investors. I mean, what’s the use of investing in electricity infrastructure if the industry can’t even generate revenues to cover its costs?

In a world where we switch to state-level electricity distribution, we cannot repeat this mistake. Electricity markets should be free of government control, meaning that residents should pay the true cost of electricity. This also means that only residents that are able and willing to pay should be connected. This free-market structure is key to securing funding and maintaining a liquid power sector. Of course, there are considerations around the risk of exclusion to consider—do we leave those who are unable to pay cut off from power supply? That’s a question worth unpacking another day.

What we know for sure though is that more funding is needed in the power sector to stop it from perpetually being on the brink of collapse.