When a conversation about mobile money happens, Safaricom’s M-Pesa is always lauded as a successful example of execution done right. Failure to identify similar traction for many other mobile money services (be it other telcos, fintechs, or traditional banks) might cause many to fear that M-Pesa’s success may never be replicated again. M-Pesa is used by over 30 million Kenyans, equivalent to more than 70% of the adult population; and around 50% of the country’s GDP flows through it.

Operators (both in Kenya and in other countries) have done their best to imitate Safaricom. A noteworthy mention includes Africa’s biggest operator, MTN, which has rolled out mobile-money schemes in several African countries. However, mobile money services in other African countries are still playing catch-up.

Key takeaways:

-

Mobile money operators in African countries, including Kenya, are playing catch up with Safaricom's M-Pesa, which over 30 million Kenyans use.

- The market for

Therefore, the questions put forward are: can other mobile money service providers achieve the same product-market fit as M-Pesa did in the Kenyan market? Or was the execution of M-Pesa business model shaped by a set of circumstances that aren’t necessarily available to other players?

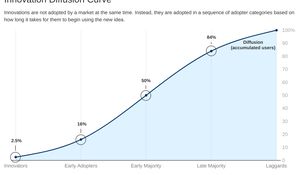

It’s important to answer these questions because mobile money is and will continue to be the dominant financial services modality used across many parts of the African continent. Over 550 million mobile money accounts have been registered since the activity started in 2007. That’s more than what you will get if you added the estimated populations of Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa—three of the largest African economies. In addition to that, the already large market for mobile money in Africa is still in its early stages and only just entering its next stage of growth. As this blog post puts it, we are only beginning to transition to Mobile Money 2.0 as the service goes from being built on top of GSM infrastructure to smartphones and leveraging the internet.

Arguably, a fundamental requirement of the mobile money service is that it disrupts the traditional financial system. This is because mobile money offers an alternative means to accessing financial services from bank accounts, which can be expensive to access and manage. The telco version of this is to move users of financial services towards a phone line, which is much cheaper to access, manage, and use. A defining attribute of the mobile money service is that you can have an account from which you can conduct financial services that does not have to be linked to a bank account.

However, it would be remiss to assume that any market, particularly the financial services one is static. This is because of changing user preferences as customers evolve to become more sophisticated users of a product, or even competitors coming in to disrupt the space. So, in answering our questions of whether other mobile money providers can replicate M-Pesa’s success and understanding the drivers of M-Pesa’s success, we must first consider the past.

Let’s start with the earliest pioneer of mobile money, then imagine the future from there.

It matters who builds

Quite recently, in one of our articles, we talked about what the role of the state in any economy should be. We agreed on two—redistribution and aiding the private sector. The second role is what is integral to what we want to discuss today. You see, for many economists who argue that the state should aid the private sector, the intention here is to encourage the state to build an enabling environment. That looks like ensuring the necessary infrastructure or laws are in place to help businesses carry out their operations smoothly. Rankings like the (now controversial) World Bank Ease of Doing Report are one way to measure this.

However, it doesn’t always look like creating an enabling environment in practice. Sometimes, states play favourites—either because they think they can pick winners (see the industrial policies in countries like South Korea) or because they have a more direct stake in the business and so naturally, want to make sure it does well. That’s one thesis that has been submitted to explain M-Pesa’s success.

What many people might not know is that Safaricom started in 1993 as a department of the state-owned telecom operator—the Kenyan Post and Telecoms Corporation. In 1997, Safaricom Ltd was incorporated as a private limited liability company. This transition from a state-owned enterprise to a private company is important to draw out because enough studies have looked into the question of whether privately-run companies are better managed (or set up for success) than those owned by the government.

This debate was largely initiated by the privatisation wave of the late eighties and early nineties when the poor economic performance of government-owned enterprises led to a preconceived notion that governments are not good at running companies.

The underlying assumption here is that the private sector is more likely to be driven by market forces, and so, a private company would be run more *efficiently* than a state-run company. This idea is not entirely wrong. State-owned companies do not have the benefit of focusing solely on making profits in the way that private companies can. However, we must remember that it is precisely because the private sector is driven by market forces that in some instances, it makes more sense for the state to step in under certain circumstances. Consider the famous example of why the market won’t provide street lights because you can’t exclude those who didn’t pay from using it. There’s also the fact that the state is more likely than the private sector to build at scale.

We have covered the debate of market versus state extensively here and here so let’s not get too distracted. Anyway, the point we are bringing out here is that it can be proven that state-backed support can go a long way in ensuring success. That’s because the state does not always play fair. You only have to look at the US’ approach to subsidising cotton farmers, which has made US farmers artificially better than farmers in countries like Chad and Mali to see how this plays out. Because of the American government’s help, if Malian farmers are paying $50 in costs, American farmers are paying $10. The unfair advantage has allowed the US to remain a significant player in global cotton production and exports. This illustrates a classic case of the state providing support to its “chosen ones”, which makes it difficult for other competitors to weigh in.

The ownership structure of Safaricom gives an important glimpse into the Kenyan government’s interest in guaranteeing Safaricom’s success. Even after the privatisation process, the Kenyan government still has a 35% stake in Safaricom, while Vodafone owns 40%. This gave the government an incentive to ensure that Safaricom did well. I came across a parliamentary investigation that drives home the point of the government’s vested interest in Safaricom. According to the investigation, 12.5% of Vodafone Kenya was given to a company called Mobitelea Ventures, which was allegedly owned by the President’s son and other high-ranking government officials.

So unsurprisingly, when Safaricom revealed its mobile money play, the Kenya Bankers Association was strongly against it. Kenyan banks did not like the idea of a telco leveraging its reach through SIM cards to provide financial services. However, the Ministry of Finance published a letter of non-objection stating that M-Pesa was not a banking service. If you remember what I said about mobile money being an alternative to traditional banking services, you should find the Kenyan government’s assertion a little surprising. To be fair, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) was correct. Mobile money was not a banking service, it was a financial service that didn’t need banking to work. That made it a direct threat to Kenyan banks. However, the MoF’s careful wording gives some insight into how the state allowed Safaricom to offer financial services without subjecting it to the regulatory burdens that banks faced.

It wasn’t just the banks as well. When other telcos attempted to launch rival services, they were met with unfair competition. A notable example was Safaricom’s decision to resist interoperability and charge double for transfers to other networks than for M-Pesa-to-M-Pesa transactions. Safaricom also signed exclusivity contracts with 80,000 agents, which forced competitors to endure the costs of building parallel networks. This is in direct contrast to a country like Tanzania, where such arrangements are banned. These are strong examples of anti-competitive measures that naturally, any government should step in to mitigate. However, challenges by Safaricom’s rivals did not yield much action from the government.

And it worked.

It only took five years from launch between 2007 and 2012 for 70% of the Kenyan adult population to sign up for an M-Pesa account. And so after establishing a base of initial users, M-Pesa then benefitted from network effects: the more people who used it, the more it made sense for others to sign up for it.

The business-state patronage (read: collusion) might sound wrong or uncomfortable but it’s not such a bad idea. Like I said earlier, the decision by states to prop up certain industries or companies within the economy can be driven by different factors including industrial policy to boost job creation and economic development. Depending on execution, these can end up reaping benefits to the wider economy.

When M-Pesa launched in Kenya, it did so with the financial regulator on its side. The Kenyan government adopted a fairly relaxed position that allowed M-Pesa to flourish and as we saw earlier, even removed any obstacles in its way. The impact of this was an uptick in financial inclusion for many Kenyans. A study shows that the introduction of M-Pesa lifted 2% of Kenyan households out of poverty. And remember, within five years it was used by 70% of the population, and 50% of Kenya’s GDP now flows through a network of more than 30,000 M-Pesa agents. By contrast, it took 115 years for banks to provide their customers with 43 licensed commercial banks, 1,045 bank branches and 1,500 ATMs.

Mobile money, more problems

As has been documented many times before, Safaricom had several factors working in its favour when it launched M-Pesa in Kenya: its dominant market position, the regulator’s initial decision to allow the scheme to proceed on an experimental basis without formal approval; a simple marketing campaign built on the need for people to “send money home”, and an efficient system to move cash around behind the scenes.

It’s difficult to accurately estimate which of these factors had more weighting in M-Pesa’s success in Kenya.

One thing we can do though is to see what happens when we remove the state-backed support but leave in everything else that M-Pesa had going for them (the brand, the efficient cash moving system, etc). A good way to do this can come from looking at M-Pesa’s success in serving markets beyond Kenya. Of course, a limitation of analysing M-Pesa's success this way is that it only gives us an idea of what M-Pesa’s impact looks like without state support, but it does not give an accurate picture. Still, it’s useful to consider. In each of these markets (South Africa, Ghana, Tanzania and others), the M-Pesa brand was retained. However, M-Pesa has 16.1 million customers across these other countries, which is fewer than what they have in Kenya. That speaks volumes when you account for the fact that the combined population of these countries is four times larger than Kenya’s population. Estimates put the average revenue per customer in these markets at around $20, compared to $32 in Kenya.

Faced with constraining regulation in other markets, M-Pesa struggled to replicate its success elsewhere. For example, in Ghana, the central bank required mobile operators to partner with banks. In addition, the Kenyan government’s reaction to M-Pesa is far from the Central Bank of Nigeria’s attitude to telcos trying to build their own mobile money services in Nigeria. We have moved on from the days of regulation that outrightly restricted telcos from participating in the mobile money space—MTN, Airtel, and 9Mobile now have payment service banking (PSB) licences. However, as we have covered previously, these PSB licences have been deliberately structured to ensure telcos don’t encroach on traditional banks’ territories (i.e. credit and FX transactions are not covered by PSB licences).

Keeping the mobile money agenda moving

However, while today’s incumbents have done a great job of spreading mobile money across Africa, their products still need to be improved. Users and observers of today’s mobile money products complain that telco-operated mobile money is expensive, with high fees levied on users for withdrawals, money transfers, and sometimes even just checking your account balance.

And pricing is not the only issue. With technology still built on legacy technology, the products themselves are not easy to use and often make for a painful user experience, which often leaves customers dissatisfied.

That’s why people get excited when venture-backed startups looking to disrupt the mobile money space step onto the scene. I always go back to Wave, a Senegalese-based fintech unicorn to illustrate what the market might look like if there was a mobile money service that delivered an excellent customer experience *and* low, transparent pricing. Their value proposition to deliver mobile money services through innovation and customer obsession reflect the evolving mobile money market that the likes of M-Pesa have taken for granted.

In an interview with TechCrunch, co-founder Drew Drubin describes Wave as a mobile money service that is “radically affordable”. The fintech charges users a 1% fee to send money, which the company claims are 70% cheaper than telco-led mobile money services. In addition, Wave is primarily available as a smartphone app. The app uses very little data—key for a region where the majority of the population has been classified as internet poor. As a result, the Wave app is accessible to users that cannot afford 3G/4G subscriptions. Users without smartphones can also access the app through QR cards, an alternative form of digital payment that grew in popularity during the pandemic.

All of this innovation and emphasis on reducing user friction with the product was integral to Wave’s success in Senegal. According to industry observers, Wave has successfully unseated incumbents like Orange Money (a telco) and Wari in Senegal.

However, for Wave to really go far, we see again how government support is crucial. Recently, Wave became the first non-telco and non-bank to get an e-money licence from the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO). The licence will allow Wave to offer a wider variety of financial services like merchant payments, savings, credit, and remittances. As any advocate of financial inclusion will tell you, delivering financial services means more than just helping people send and receive money. They need to be able to do other things like borrow money from the future so they can afford the things they need today. This is not implying that any government has a stake in Wave, but instead, it points to the importance of having the right kind of government regulation to help any business gain traction. It does not have to look like outright favouritism as we saw with M-Pesa, but the government is crucial for any business’ success.

Generally, some of the factors behind M-Pesa’s lead cannot be copied; and they might not need to. As has been argued previously, the telco-led version of mobile money can be referred to as the first iteration (or mobile money 1.0 if you may). That means that as we build for a new mobile money future, other things like improved user experiences will matter more. My view is that the state backing will always be a useful edge for building a successful business. The current structure of Safaricom reflects a happy mix of private and public cooperation that has allowed M-Pesa to flourish. That is something that disruptors in the mobile money space need to have at the top of their minds as they build.