Go on Twitter and everyone is so sure we are either in or heading towards a recession.

Everyone living in the United States (US) at least, whether by physical address or Twitter timeline. Former Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein said at the weekend that the US economy risks entering a recession this year. Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal in April estimated a 28% probability of a recession in the next twelve months, more than double the probability in April 2021. Even Twitter’s would-be acquirer Elon Musk tweeted last December that he anticipates a recession in Summer 2022.

Key takeaways:

-

The likelihood of a recession in the next 12 months keeps increasing as business leaders such as Elon Musk and Lloyd Blankfein weigh in on the market contraction trends we have been observing

- However, a good way to predict the financial future is by looking at company prices. The

When the US economy sneezes, we all catch a cold, reason alone for us to be worried about the Nigerian economy without even thinking about our internal problems from rising unemployment & insecurity to poor public finances & stalling governance.

Is Nigeria also heading towards a recession? Are we already in one? Is the US?

Leading indicators point towards a US recession

Harsh as it may be, it’s important to begin our answer by acknowledging that economists in the US have predicted ten out of the last five recessions and yet always seem to be caught by surprise. As Musk himself admitted in his December tweet, predicting macroeconomics is hard. Ironically, the only people that don’t like to admit this are (most) economists. Interpret all predictions, as well-intentioned and data-backed as they may be, with some level of caution.

Having said that, there are valid reasons to be gloomy about the US economy.

Financial markets—as chaotic as they are—are also used as leading economic indicators, i.e. their performance today tells you what tomorrow’s economy may look like. By that metric, tomorrow is bleak for many Americans.

The closest thing macroeconomists have to an early warning signal for recessions in advanced economies is the fixed income yield curve. It’s basically a chart that plots different-tenured fixed income assets (e.g. 6-month treasury bill, 10-year bond, etc.) with their corresponding yields (interest rate) at the time. A normal yield curve is upward sloping, so the longer the bond, the higher the yield, the intuition being that I take on more risk if lock my money down for 10 years than for 6 months.

When the yield curve inverts and shorter-tenured assets instruments have higher yields than longer-tenured assets, investors begin to panic as the implicit message is that the short term is much riskier than the long term. An inverted yield curve means that investors expect longer-term interest rates (or returns) to be lower than in the near future. For example, if investors expect lower returns on equities five years from now, they will accept lower returns on five-year bonds selling today.

The mechanics of fixed income yield curves are extremely complex. Some have argued that the US Federal Reserve (central bank) rigged the yield curve with its decade-long quantitative easing program that flooded financial markets with cheap money. Some argue that inflation expectations play the biggest role. Very few people know the absolute truth, if there even is one.

But it is hard to dispute the predictive power of the yield curve.

Inverted yield curves have preceded every single US recession since 1955 and only given one false positive during that period.

Today, the US fixed income yield curve is inverted, and everyone is arguing for why this time is different.

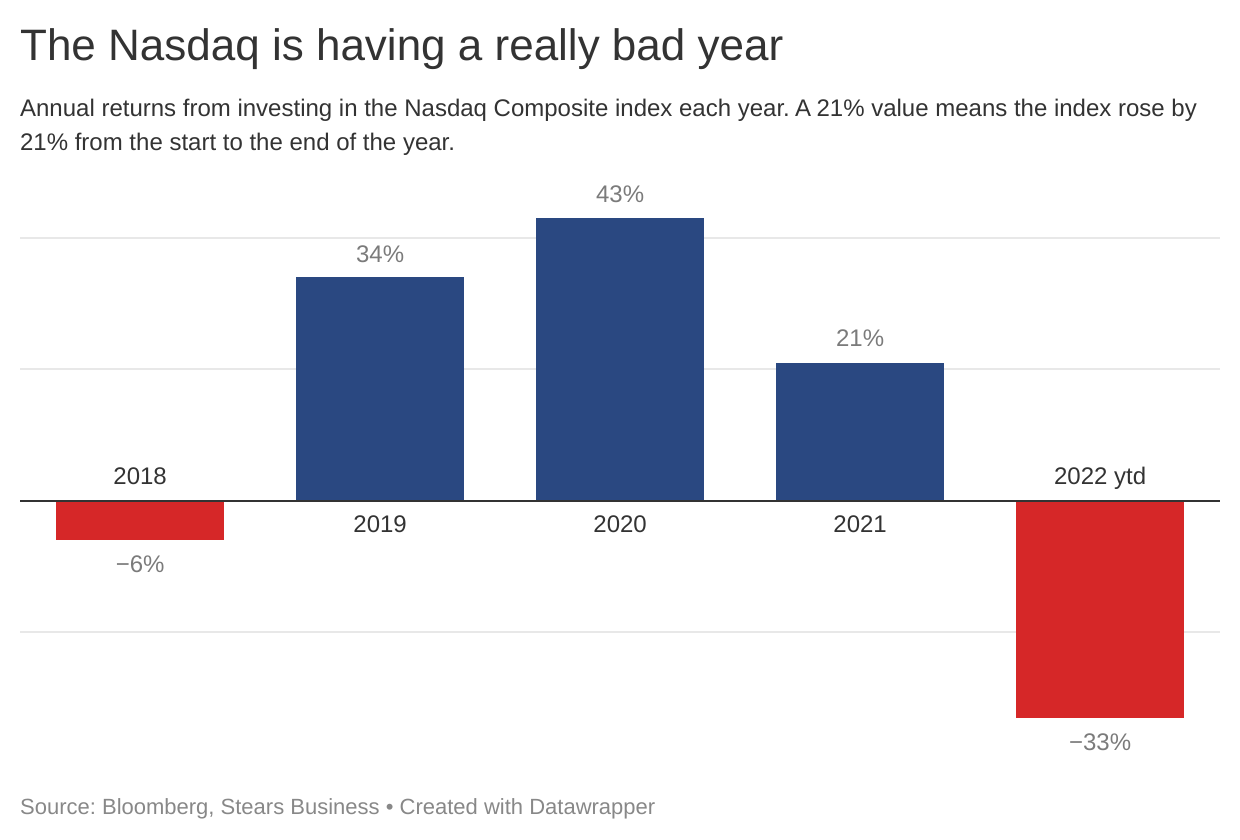

To see the folly of “this time is different” thinking, look at the other big financial market in the US: equities. The Nasdaq Composite, one of the “Big Three” in the US and the most tech-heavy, has lost a third of its value in 2022.

A third of its value. In four and a half months. Compare that to performances in the preceding years.

The past few weeks have been a bloodbath. By the end of last week, the Nasdaq Composite had lost over 20% of its value from the start of April and was 36% down from its record high in November 2021, the first time the index breached the 16,000 point mark. As a comparison to that 36% drop, the peak-to-trough decline in the Nasdaq following the 2020 pandemic was 41%, but as the chart above shows, the index still closed positive in 2020.

The odds of a positive close in 2022 are looking slim.

This matters because in the simplest world, a company’s share price is a financial prediction of its future. Ignoring those pesky animal spirits, falling share prices tells us that investors expect lower profits in the future. So share price movements tell us where the economy is going.

Unfortunately, financial markets are not the only indicator of doom for the US economy. Expect to hear a lot about the US fed (Federal Reserve) in the coming twelve months as the US apex bank has become a de facto central bank for the Global North. They are now probably the most powerful economic entity in the world as they determine how quickly and by how much to raise US interest rates to combat inflation.

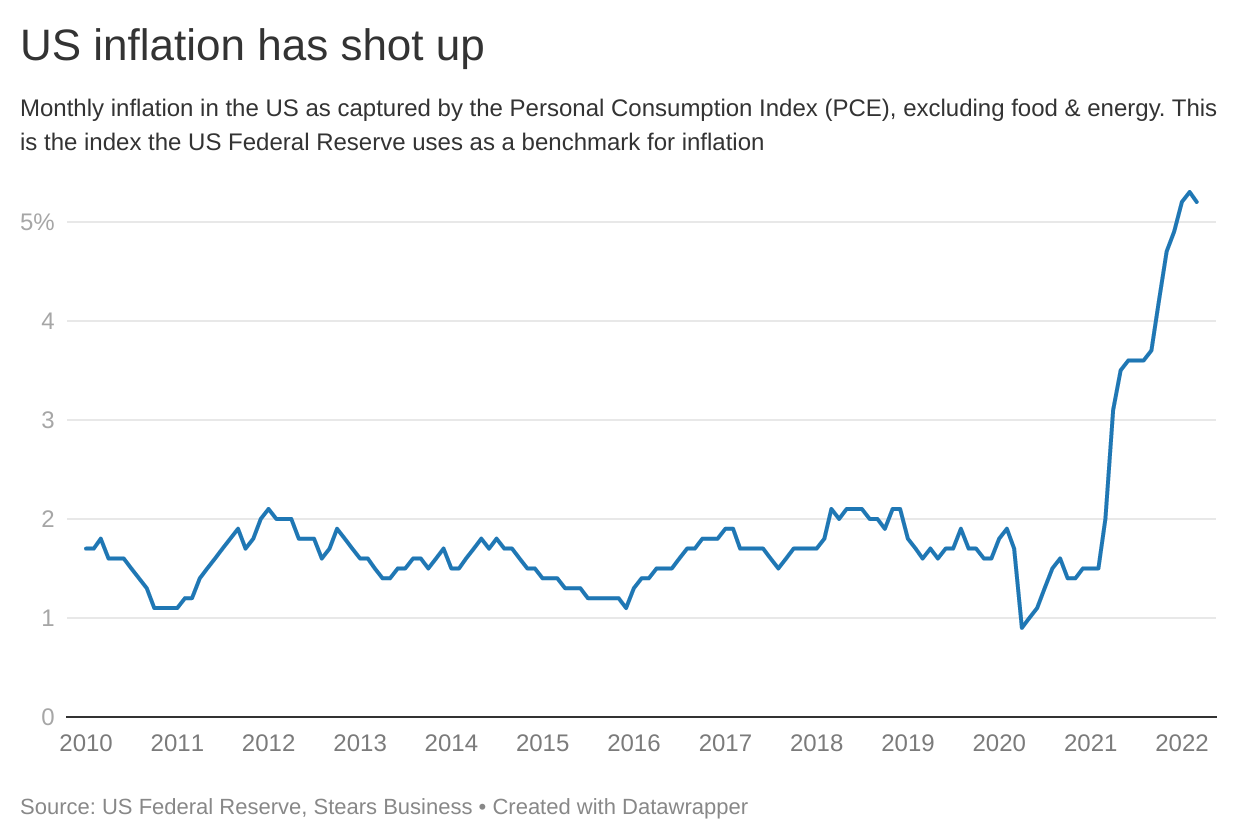

And make no mistake about it, inflation in the US is accelerating rapidly.

The chart below shows monthly inflation in the US. But it focuses on prices that the Fed can (in)directly control, so doesn’t account for house prices (similar to Nigeria’s inflation metric), food, and energy. This is important because food and energy are the most volatile parts of the inflation basket. That statement is still true for both the US and Nigeria today.

This “core” inflation is rising very quickly, very suddenly in the US. From 2010 to 2020, core inflation averaged 1.6% a month in the US, comfortably below the Fed’s 2% inflation threshold. This point is worth reiterating as prices remained relatively stable even as the Fed embarked on an aggressive and experimental monetary policy approach that essentially involved them printing new money and flooding financial markets. Many economists warned about inflation for decades but nothing happened. In fact, inflation was higher in January 2008 (2.2%) at the onset of the financial crisis than in December 2020 (1.5%).

Something changed a year ago.

In March 2021, core inflation reached 2% for the first time in over two years. A year later, in March 2022, core inflation was 5.2%, 50 years after core inflation in the US last exceeded 5%.

Unprecedented times, indeed.

With this level of core inflation, it is hard to see the Fed not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. We haven’t even factored in the realities of global food and energy prices. The United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) global food price index estimates that basic food prices are up 19% already this year, after rising by just 6% in 2021. Meanwhile, the rise in energy and commodity prices is well-documented.

All in all, whether the US enters a recession or not, the near future doesn’t look great. Are things rosier in Nigeria?

The Spirit of the Thing and the Thing Itself

Before we consult our crystal ball for the Nigerian economy, it’s worth distinguishing between the spirit of a recession and what it actually is.

The most well-established definition of a recession is when an economy experiences two consecutive negative quarters of economic growth, i.e. GDP falls for two consecutive quarters. This definition is very helpful because any country can use it and two quarters (six months) should give us enough time to weed out transitory events (e.g. the US 2020 “recession” lasted just two months). But it doesn’t tell us which GDP we should be comparing to for the growth rates.

Nigeria looks at year-on-year GDP, so a recession today means that GDP this year has fallen compared to last year. And a recession in the third quarter of 2022 means that GDP in the third quarter of 2022 is lower than GDP in the third quarter of 2021 (and vice versa for the second quarter). This eliminates any seasonality in GDP (e.g. harvest vs planting seasons in agriculture). Other countries (e.g. the US) look at GDP on a quarter-on-quarter basis, so a recession in the third quarter of 2022 means that GDP in the third quarter of 2022 is lower than GDP in the second quarter of 2022. This approach to computing GDP growth (and recessions) is more volatile and less popular, but no one would argue with you if you said Nigeria or the US entered a recession using this approach.

Thus, there are different ways of measuring GDP growth and they tell different stories.

Even more importantly, the accepted definition of a recession is negative GDP growth, i.e., for GDP to decline. This means that a country that experiences this sequence of quarterly GDP growth will be in a recession—5%, -0.5%, -0.5%, 5%, while a country that experiences this sequence of quarterly GDP growth will not be in a recession—0.7%, 0.2%, 0.1%, -0.5%.

But when we speak about recessions, we aren’t just talking about negative GDP growth over consecutive quarters, we are trying to capture a general experience of the economy getting significantly worse in a short space of time. This is why periods of recession (e.g. the 2016 recession in Nigeria or the 2009 global recession) stick in people’s minds—life got much worse from an economic perspective.

It is arguable that recessions don’t always capture this accurately. For example, the second sequence of GDP growth is arguably worse than the first even if the country never technically entered a recession.

All of this is important because, as crazy as it sounds, it’s hard for some countries to enter recessions or stay there. That’s why Nigeria has only had two in the last thirty years (both coming since 2014). For smaller, growing economies, it is actually quite difficult for GDP to decline consistently over a period of time. It is much more likely for GDP growth to slow significantly. And the truth is that the experience of each scenario is similar.

Consider that the Nigerian economy was only technically in recession for three months in 2016 (overall annual GDP growth: -1.6%). But the experience of tough economic times lasted much longer. According to GDP metrics, the Nigerian economy grew by 0.8% and 1.9% in 2017 and 2018, but it felt like a recession, not in subjective terms, but using a similar gauge we use to determine tough times.

All of this is to say that although Nigeria is very unlikely to enter another recession this year (or next), (much) tougher economic times still lie ahead.

We may be headed to a recession in spirit, if not on paper.

What recession?

The case against Nigeria-heading-to-a-recession is a simple one to make: not enough has changed or looks like it will change for the next 12 months to warrant that view. As dilapidated as the economy is today, it’s still floating above water. We are already in the middle of a five-year dollar crisis, a three-month energy crisis, and a god-knows-how-long governance crisis. What exactly will tip the Nigerian economy over the edge?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expressed a surprisingly similar optimistic view a month ago when it released its World Economic Outlook and increased its projections for Nigeria’s economic growth from 2.7% in 2022 and 2023 to 3.4% in 2022 and 3.1% in 2023. The IMF is more optimistic about Nigeria’s near-term economic growth prospects than at the start of the year.

The same IMF reduced its forecasts for global GDP growth for 2022 from 4.4% to 3.6% and 2023’s from 3.8% to 3.6%. So they believe tough times are coming, just not for Nigeria.

Oh… this recession

Even with the IMF’s bullishness, there are reasons to be sceptical.

First, it is really hard to internalise just how bad Nigeria’s energy situation is. We’ve spoken about it in detail, starting from the root cause (our price-fixing addiction) to our gas ineptitude and the spiraling costs of retaining subsidies. These problems are just starting, as you can tell from recent warnings of another petrol scarcity.

The second worry is contagion. Ironically, it may be the global economic slowdown that comes back to haunt Nigeria. Already, in the tech ecosystem, Nigeria’s golden goose, there are concerns that the collapse of both public (e.g. equities) and private (e.g. venture capital) markets will weaken investor appetite for Nigerian startups. And we know that almost all other investment has long-since dried up.

The third point is that, once again, Nigeria’s economic growth numbers (forecast or otherwise) may not reflect the economic realities of many Nigerians.

Here’s the thing: recessions are natural. Let’s quote out favourite CEO again. “Recessions are not necessarily a bad thing. What tends to happen is if you have a boom that goes on too long, you get a misallocation of capital. It starts raining money on fools, basically,” Musk argues.

Basically, boom-and-bust is the story of every financial system and economy ever. The last time a prominent economic policy-maker dared to suggest that the boom-and-bust may be over, we faced our worst global recession since the Great Depression.

Remember that anytime someone tells you that the market for crypto will not be boom-and-bust for the foreseeable future.

Anyway, this means that recessions—like toothaches—are painful but rarely fatal. Like toothaches, they become real problems when they are fatal. For a recession to be fatal, the economy needs to go boom, then bust, then stay there…

That’s the prospect that Nigeria faces today. Whether or not the economy technically enters a recession, it is vulnerable enough today for there to be long-term implications.

The 2016 recession left an enduring legacy: the exchange rate went up and has kept rising, inflation went up and has kept rising, unemployment went up and has kept rising, and so on.

The potential legacies of the 2022/2023 economic slowdown are the real worry. Nigeria’s economy in 2015 was relatively robust. A decade of >5% GDP growth, large external reserves, and so on. We’re still living through the last days of that recession.

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic was also a huge wake-up call. Even though Nigeria was only mildly affected by the pandemic and barely adhered to a month-long national lockdown, the economy was temporarily decimated as the pandemic revealed all the underlying faults: fragmented local supply chains decimated by the 2019 border closure, a weak domestic credit mechanism that meant that CBN itself had to basically hand out cash to distressed businesses, and so on.

Imagine what we will get if we take today’s Nigerian economy—battered, broken, and desperately pining for May 2023—and what looks like the worst natural global slowdown since the 2009 recession.

Rising debt and a federal government committing 98% of its earnings to debt servicing. An oil economy that can’t produce oil or petrol. Inflation nearly double the central bank’s 6-9% threshold. Then toss in the fragile security situation and the looming 2023 elections and you get a chaotic cocktail of calamity.

Recession or not, the sirens are calling loud and clear. Strap in.

*This article was amended on the 31st of May. The US Federal Reserve can be considered the de facto central bank for the Global North, not the Global South.