It is an incredibly exciting time to be in Nigeria’s technology startup ecosystem.

Despite widespread economic malaise, Nigeria’s Telecommunications and Information Services, the best proxy for the growth of tech-powered companies in the country, has grown by 57% since 2017, compared to overall national GDP growth of 6%. In effect, the sector has grown ten times faster than the wider economy in the last half-decade.

Key takeaways:

-

There is a lot of excitement in Nigeria’s tech ecosystem, given the fundraising activity and the high valuations that follow. However, there have been rising doubts about the sustainability of startup valuations given the current economic malaise that troubles the Nigerian economy

-

It is important to think about valuations because they matter for the investors who fund startups and the founders who run them

- However, it is not possible to get a meaningful answer to the question of whether Nigerian startups are overvalued

Yet that’s not the most impressive statistic.

In 2021, Nigeria’s startups raised $1.8 billion in venture capital (VC) funding, more than Kenya and South Africa combined ($1.4 billion). And the money keeps rolling in. In the first quarter of 2022, Nigerian startups raised $600 million, nearly double the amount raised in the whole of 2020 and 80% of the 2019 value. In fact, 2019 is the only year where Nigerian startups raised more than $600 million—the value they have raised so far in 2022.

Everyone is excited. Well, not everyone.

In the last six months, especially as many technology stocks in global public markets have tanked and Nigeria’s domestic economy continues to stall, questions have been raised about Nigeria’s tech ecosystem. Questions not about the growth or impact of startups, but about their valuations. In a hyper-positive ecosystem, it remains a fringe idea, but a few people—mainly ecosystem veterans and investors—are beginning to ask: are Nigerian startups currently overvalued?

These worries are primarily driven by notable growth in the average deal size, especially for early-stage startups. Few people (until recently, at least) query valuations for Flutterwave, Andela, and co, but eyebrows are sometimes raised when an unknown fintech raises a $1.5 million pre-seed round. Five years ago, pre-seed deals would rarely exceed $100,000.

The trend in average deal sizes provides some empirical support to this anecdotal view of deal size inflation. Looking at Partech Africa data on the continent, the average seed deal increased from $1 million in 2018 to $1.2 million in 2021, and the average Series A deal more than doubled from $4 million in 2018 to $8.8 million in 2021.

The valuation conversation is one worth having, if only because it benefits no one in the long run if founders and investors alike buried their heads in the sand. Furthermore, grappling with the issue should help adjacent ecosystem stakeholders like regulators and employees better understand the dynamics of market sizing and the underlying philosophy of startups.

But to properly answer the question, “Are Nigerian startups overvalued?” we need a better understanding of the type of answer that is possible and why the answer is important to the ecosystem.

We tackle both here.

You are not going to get an accurate and generalised answer to the valuation question. Not just because the valuation of any company is more art than science, but because valuing most Nigerian startups—still predominantly early-stage—is more an exercise in philosophy than finance. There is a lot to say to unpack this, so we will go through four important justifications for this view.

You won’t get a consistent answer to the question

This is an obvious, practical limitation to answering the valuation question. It is also true of companies all over the world, so it need not be fatal to our ambition here. We will see that even if the heterogeneity of Nigerian startups doesn’t make the valuation question redundant, it makes it a lot trickier to tackle.

Let’s start with a broad generalisation that is roughly true. There are two main factors that determine the long-term value of a start-up (or any company):

-

The long-term size of the market (market potential).

-

The start-up’s ability to capture that market (business execution).

Looking at the first one, how do we estimate a start-up’s market size? Well, it depends on many factors: the state of the economy, consumer spending power, businesses’ health, internet access and cost, asset ownership, sector, product, and so much more.

The estimate of a start-up’s market size is also extremely time-dependent. One common mistake people make is evaluating start-up potential based on current opportunities or market trends, when the promise of a start-up is its ability to create or capture future market opportunities as it reaches scale.

None of this is new.

Here’s how it becomes difficult to answer the valuation question in Nigeria’s early-stage startup ecosystem. If you had two similar early-stage startups at similar stages providing similar services in the same sector, their estimated valuations could differ significantly because their perceived market sizes are so different.

To see how this is possible, consider a fintech consumer lender focused on leveraging inexpensive virtual distribution channels and competitive interest rates to penetrate Nigeria’s credit market. As we have seen from the relative boom in Nigeria’s consumer credit market, there is potential here. However, this startup is creating a market-sustaining innovation—it is simply improving the way consumer credit is delivered today.

Consider another fintech consumer lender that does the same, but also layers an Open Banking piece focused on building interopability with other financial institutions. Its goal is two-fold: to penetrate Nigeria’s credit market and help strengthen credit market infrastructure through data. This startup is building a market-enabling innovation—it is building products that expands its future market size and that of other startups too.

This distinction alone—market-sustaining vs. market-enabling—can lead to very different market size estimates (and to some extent, valuations) for startups that look very similar. And this distinction is particularly important in Nigeria’s startup ecosystem because the ecosystem, broader economy, and national infrastructure base are young enough for there to be numerous opportunities for market-enabling innovations. It also means that when we eye Nigerian early-stage startups raising at mouth-watering valuations, it is worth asking if the company is building market-enabling solutions (e.g. Pngme, M-Pesa, Ethereum).

Beyond the type of innovation, a startup’s business model in Nigeria can also be extremely important. The near-zero marginal cost of software is a huge justification for one-year-old Nigerian companies being valued at $5 million—they may not look like much now, but the idea is that they can leverage the distribution power of the internet to quickly capture a large slice of a large market. The likes of Meta and Amazon are held up as patron saints of this philosophy.

But the story is a bit more complicated in Nigeria. For the same reasons there is so much opportunity for market-enabling innovation: physical and virtual infrastructure remain rudimentary and access to the internet and electricity require a lot of work. This means that it's much harder for Nigerian startups to eat their market with software alone. No surprise then that Nigerian startups are not as asset-light as their international peers. In fact, the likes of Moove Africa and Paga, two of the country’s more successful startups, embed a substantial physical element (moveable assets, agent networks, etc.) into their models. Some ecosystem veterans even argue that you cannot hack B2C distribution in Nigeria with a purely virtual model.

This discussion is important because it changes the mathematics of startup valuations in a fundamental way. A simple distinction—asset-light vs hybrid—would make a significant difference to the addressable market and success quotient of the startup, especially at the early stage, where many Nigerian startups fall.

There are other factors to consider here, but the overall point is this: the fundamental heterogeneity of Nigerian startups, and how that impacts their long-term market size estimates, makes it difficult at this point to intelligently answer the question of whether Nigerian startups are overvalued or not.

You won’t get an independent answer to the question

We said earlier that two big factors determine a startup's success: market potential and business execution. The preceding section highlights how market potential affects the valuation question; here, we look at the role of business execution.

Specifically, the claim here is that it is difficult to get a meaningful answer to the valuation question since so many important external factors determine a startup's execution success.

Let’s take two of the many factors here: regulation and liquidity.

Regulation is easy to understand. In a country where the Minister of Information can ban one of the world’s largest platforms overnight, the premier city on the continent can push out ride-hailing startups on a whim, and no one is too far for the Central Bank of Nigeria to sanction, startup valuations can go from $1m to $10 million and back again, depending on the mood of regulators.

In a world of such uncertainty—unmeasurable or unpredictable risk—numerical valuations look a bit nonsensical. This perspective lends some credence to the brewing concern over Nigerian startup valuations: is company X really worth $50 million if a regulator can wipe out that value in one fell swoop?

The other big factor is liquidity, i.e. funding.

Liquidity matters in two ways. First, the more cash startups can raise, the easier it should be for them to scale and justify their valuations. Second, the more liquidity in the ecosystem, the more likely that startup valuations are inflated. This is simple economics and speaks to the basic definition of inflation: too much money (investor funding) chasing too few goods (startups).

The point here isn’t that the Nigerian ecosystem currently has too much liquidity; the point is that the amount of liquidity in the ecosystem—which, in many ways, is an external factor—would have a significant impact on startup valuations, regardless of the underlying robustness of these businesses.

Again, this provides some ammunition to the cynics in the ecosystem who worry that the entrance of market-makers like Tiger Global is having a knock-on effect on ecosystem valuations, even though underlying metrics don’t warrant it.

Wherever you fall on this debate, one thing is clear: startup valuations depend on important and volatile external factors they cannot control (e.g. regulation and liquidity), which makes it difficult to intelligently answer the valuation question.

You won’t get a data-driven answer to the question

We would be mistaken to think there is an empirical answer to the question of whether Nigerian startups are overvalued.

Even valuing established companies is far from a scientific exercise in any situation. Consider, for example, how common it is to see wild swings in the share price of publicly listed companies each day. Corporate finance theory tells us that a company’s share price is a reflection of the net present value of the company’s future earnings. Based on that alone, it makes no sense for a company’s share price to drop by 25% overnight—surely estimates of future earnings cannot change so drastically in 24 hours—as we frequently see in global stock markets. Of course, these price movements are not driven by fundamentals, but by animal spirits.

There are other examples of this. For example, two similar global investment banks (e.g. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley) could differ widely on their target price for Apple, the world’s largest company by market capitalisation. If two of the world’s most sophisticated investment banks differ so significantly on the value of one of the world’s most transparent, highly-traded companies, what hope do we have for a one-year-old startup in Nigeria?

This is an important point. We should expect startup valuations to be less accurate and more volatile than other companies because startups are younger and more opaque. Oftentimes, even the founders of early-stage startups don’t understand what the business is or will be. Knowing that, arguing about whether this company should be worth $5 million or $10 million looks futile. Furthermore, publicly listed stocks are priced every millisecond based on the supply and demand of shares at each moment. Given how frequently this pricing happens, you can expect share prices to be more precise over time. In contrast, startups are valued much less frequently—usually only at liquidity events like a raise or exit—so you would expect much less precision in our valuations.

The other reason we won’t get an empirical answer to the valuation question is that numbers are the inputs in our valuation models, not the outputs. In short, even if we had all the data in the world, we would not all agree on how much Flutterwave or Okra are really worth.

Data does not tell us the assumptions or formulas we should use in our valuation models. Even when we use industry benchmarks and other references, we are ultimately making subjective judgements that mean it is no longer a purely empirical exercise.

This point is particularly important as we have more rigorous conversations about ecosystem valuations. By all means bring the data, but don’t think the data answers all the questions.

You won’t get a real answer to the question

Now for the real philosophy.

The truth is that valuing startups, especially early-stage startups is a bit like dividing by zero; it doesn’t make much sense.

There are a number of reasons for this, and importantly, all of them stem from the fundamental nature of startups, i.e. this is a feature of the startup ecosystem, not a bug.

A startup is a company designed to grow fast and capture a meaningful slice of a big market. Its value today is based on its perceived ability to achieve this goal. This means that even pre-product, pre-revenue startups can be “valued” at $100 million because neither revenue nor products matter as much as growth potential (which can just be based on a team and an idea). This is important because it tells us something else that is very important to remember: a few of Nigeria’s dominant startups no longer qualify as such. The likes of Flutterwave and Andela have more in common with large corporates like Nestle and Access Bank than seed stage startups like Klasha or Mecho.

Early-stage startups are the “purest” form of startups and are most afflicted by the valuation paradox. But many Nigerian startups are at early stages—pre-seed, seed, and Series A. These are also the companies whose valuations have raised eyebrows in the last six months.

Rather than explore some of the underlying reasons why valuing early-stage startups makes little sense, I would just point out that the ecosystem implicitly accepts this idea and resolves it through valuation caps and SAFEs.

Basically, when a Nigerian startup raises a pre-seed or seed round, it rarely does so at a set valuation (e.g., a $1 million raise at a $10 million valuation). Instead, that $1 million raise would be done with a valuation cap of $10 million. Typically, a startup would raise $1 million through a SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) which gives investors a right to convert their investment into shares at a later date (usually at the next round). The valuation cap sets a valuation ceiling at which that conversion can happen—essentially protecting the investor from too much dilution—but also does something important: it allows the startup and investor to avoid valuing the company at the time of the present raise. In short, valuation caps are not a valuation of the company based on the company’s current projections or assets.

Valuation caps are a nice compromise between the need to specify how much an investor’s contribution is worth (at a later date) and the absurdity of valuing super early-stage companies, many of which will pivot frequently until they find product-market fit.

Startup valuations don’t make sense but are very important

There you have it. Answering the question, “Are Nigerian startups overvalued?” is rather nonsensical because:

-

You won’t get a homogenous answer to the question.

-

You won’t get an independent answer to the question.

-

You won’t get an empirical answer to the question.

-

You won’t get a real answer to the question.

Despite all this, it is extremely important that we tackle the question because startup valuations matter—even those for super early-stage pre-product startups.

Let’s look at this from two perspectives: founders and investors.

More money, more problems

It is easy to see why high startup valuations would be good for founders. The higher your startup is valued, the more your equity is worth. Furthermore, higher valuations mean you can raise the same amount of money at lower dilution. Today’s seed stage fintechs can raise $1 million in exchange for 10% of their startups; their predecessors from five years back would have had to give up half the company to raise $1 million.

And don’t forget, higher valuations are good for the ego.

But there’s a misconception that higher valuations are always good for founders. That isn’t the case. Higher valuations lead to higher expectations. Consider these seed fundraising options for a company with average annual revenues (ARR) of $100,000:

-

Raise $1 million at a $10 million valuation.

-

Raise $2 million at a $20 million valuation.

The second option looks obviously more attractive: more money at a higher valuation!

But let’s see how things could play out after 18 months. Let’s say that post-raise, the company reaches an ARR of $500,000. If the startup had gone for the first option, it could look attractive to some follow-on investors after 5x recurring revenues in 18 months. On the other hand, a startup that took Option 2 would be expected to do a lot better ahead of its Series A, e.g. $1m in ARR.

Of course, the argument is that choosing option 2 should lead to higher ARR but that isn’t necessarily true as the relationship between a startup’s cash and revenue isn’t linear. Hiring twice as many engineers may not help you launch in half the time, spending twice as much on Google Ads may not give you two times the customers, and burning twice as much cash may not make you scale twice as fast.

In fact, a startup that chooses Option 2 could find that it has traded time for money which has diminishing returns. As argued in this post, “Runaway valuations set you up on a trajectory that is wholly unrealistic. Each new bar for a milestone will suddenly become much more difficult to achieve.”

Higher valuations can make the same results look more underwhelming and even lower your chances of a raising follow-up round. Later on, higher valuations can even shrink your exit opportunities. If you raise a Series B at a $100 million, your new investors will scoff at a $250 million acquisition offer 18 months later, whereas they may have jumped at it if you raised at half the valuation.

All of this means that getting the “right’ valuation matters to founders. A lower valuation would force you to choose between raising too little capital or enduring more dilution. But a higher valuation increases expectations, reduces your long run experimentation time, and could make it harder to reach future liquidity events.

Valuations affect investor returns

Valuations also matter to investors.

Consider a pre-seed startup that needs $250,000 to build and test its product. Imagine an investor giving it two options:

-

Raise $250,000 at $1 million post-money.

-

Raise $250,000 at $2.5 million post-money.

You would think that investors would be more keen on the first option, after all, they get a larger chunk of the company. But the investor-founder dynamic is a classic example of principal-agent problems in economics. Put simply, to avoid moral hazard, investors need to make sure that startup founders (and early employees) are incentivized enough to grow the startup’s value in the early years. Since they cannot properly incentivise them through salaries (which would make the startup too expensive to run), they need to leave enough of the company to them. Hence why pre-seed and seed investors would rarely take more than a combined 10% - 20% of the company’s ownership.

But Option 2 introduces a different danger to the investor: dilution would depress its eventual return on investment.

Let’s see how this works with a practical example, inspired by this analysis of Stripe’s acquisition of Paystack.

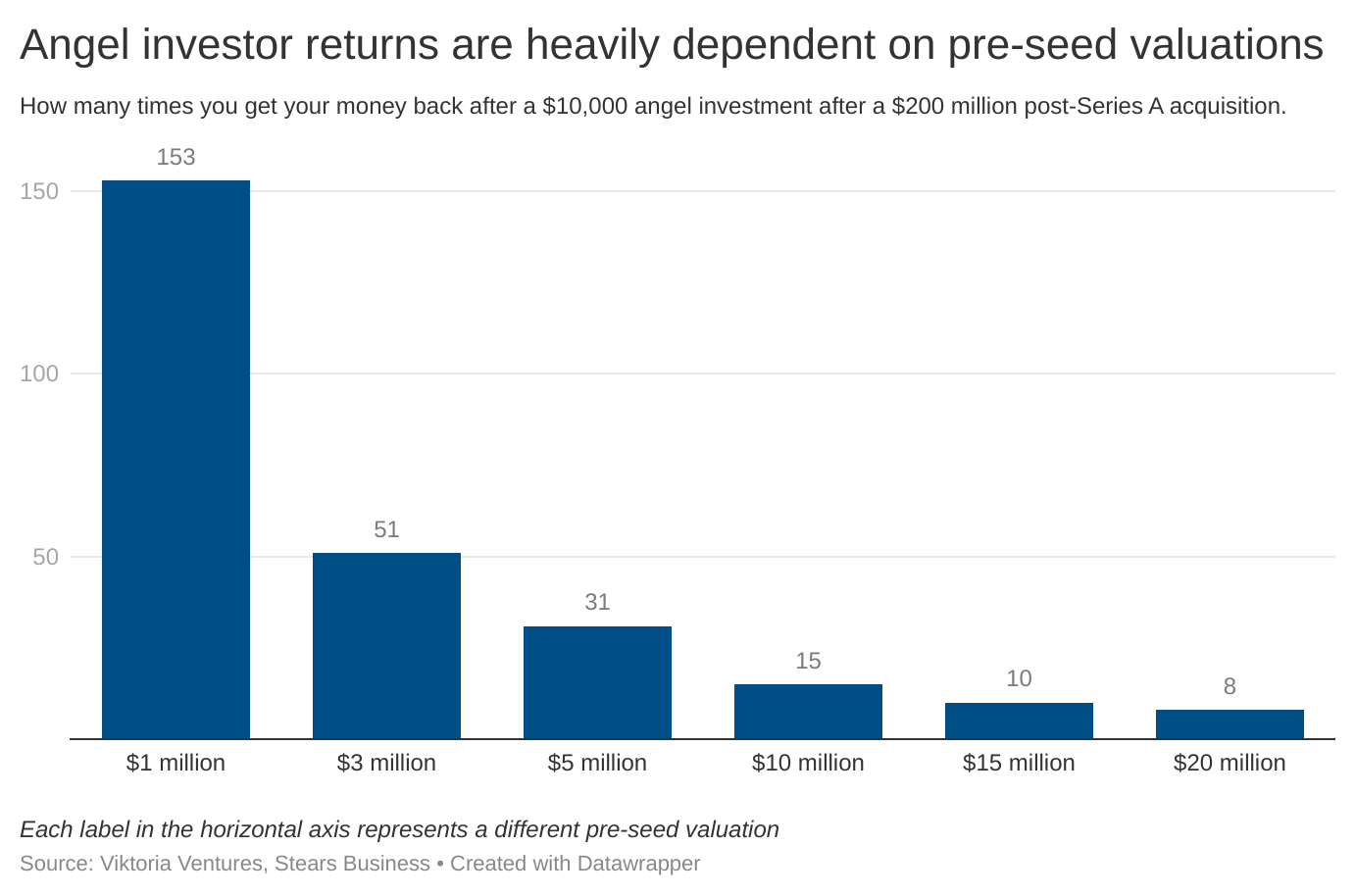

Remember, Stripe acquired Paystack for $200 million in 2020. Can we estimate what an angel investor would have made with a $10,000 pre-seed cheque? We can try.

We can make the following assumptions to help us:

-

Each round takes place a year after the last round.

-

Each round, the investment is diluted by 10-15%

-

The company raises a seed round at a $10 million valuation.

-

The company raises a Series A at a $50 million valuation.

The chart below shows how many multiples on the initial investment ($10,000) that the angel investor makes depending on the initial pre-seed valuation (cap).

You don’t need to understand the computations to understand the point. The same investment amount ($10,000) can lead to wildly different returns even when we hold all other variables (e.g. dilution) constant, all because of the initial pre-seed valuation of the startup. A $10,000 pre-seed investment at a $1 million valuation would have led to a 153x return at the $200 million sale. While the same investment at a $10 million valuation would only get you your money 15x back.

The story here is that for investors, especially those at the early stages, valuations matter a lot when estimating your eventual return.

Why does all this matter?

This article makes two important but slightly conflicting points. The first is that it is not possible to get a meaningful answer to the question of whether Nigerian startups are overvalued because valuing Nigerian startups is more philosophy than art or science. The second is that even if valuations are largely nonsensical, they remain extremely important for founders and investors.

The slight conflict between the two points—valuations are meaningless and significant—brings us back to why it is so important to have these conversations, not so we can get a definite answer, but so we can explore and properly discount all the relevant factors that make us excited about Nigeria’s many early-stage startups.

Only posterity with tell if Nigerian startups are undervalued, overvalued, or just right, but it’s our duty as members of the ecosystem to keep probing the numbers and the logic that drives them.